The ancient Greeks, a civilization oft-celebrated for its philosophical prowess, dramatic artistry, and democratic ideals, also left an indelible mark on the landscape of human technological achievement. Their engineering feats, though lacking the sophisticated machinery of later eras, were characterized by an ingenious application of fundamental scientific principles and an unwavering dedication to practical problem-solving. This article delves into the remarkable construction and hydraulic innovations that underpinned their society, revealing the intricate methods by which they shaped their world.

The bedrock of Greek construction lay in their profound understanding and sophisticated manipulation of natural materials, primarily stone and timber. Far from being mere brute force efforts, their building projects exemplified meticulous planning, precise execution, and a deep appreciation for structural integrity.

Quarrying and Transport: The Herculean Task

Before a single stone could be laid, it first had to be extracted from the earth. Greek engineers developed highly effective, albeit labor-intensive, methods for quarrying vast quantities of stone, predominantly marble and limestone. The process involved identifying suitable rock formations, often through geological surveys, and then utilizing a combination of tools and techniques.

- Wedge-and-Feather Technique: This method involved drilling a series of holes into the rock face along a predetermined line. Metal wedges, often made of iron, were then driven into these holes, sometimes with the aid of water to expand them. The immense pressure generated by the expanding wedges caused the rock to split cleanly along the desired plane. This technique allowed for the extraction of large, precisely cut blocks, minimizing waste and maximizing efficiency. The uniformity of these blocks is evident in the surviving structures, where the joints between successive courses of masonry are remarkably tight.

- Leverage and Rollers: Once quarried, these colossal blocks, frequently weighing many tons, had to be transported, sometimes over considerable distances, to the construction site. The Greeks employed an intricate system of levers, ramps, and wooden rollers. They understood the principles of mechanical advantage, using long levers to lift and pivot heavy stones. The use of rollers, often lubricated with water or oil, reduced friction, allowing teams of laborers and oxen to move objects that would otherwise be immovable. These overland transport operations were engineering marvels in themselves, requiring carefully planned routes and considerable logistical coordination.

- Sea-Based Transport (When Applicable): For sites near the coast, sea transport offered a more efficient alternative for massive stone blocks. Specialized barges, often reinforced, were used to ferry materials, leveraging the buoyancy of water to overcome the gravitational challenges of land transport. This method proved particularly crucial for islands or coastal cities where land-based routes were impractical or too arduous.

Architectural Innovations: Columns, Gables, and Foundations

Greek architecture is immediately recognizable by its iconic elements, such as the column and pediment. However, the engineering behind these stylistic choices was equally significant, demonstrating an advanced understanding of load distribution and structural stability.

- Column Construction and Fluting: Greek columns, especially those of the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian orders, were not merely decorative. They served as primary load-bearing elements, transferring the weight of the entablature and roof to the foundations. While some columns were monolithic, many were constructed from a series of drums, precisely carved to fit together with remarkable accuracy. These drums were often joined by a central wooden or metal dowel, providing additional stability. The fluting on the columns, though aesthetically pleasing, also contributed to the visual perception of height and slenderness, an optical illusion that enhanced the grandeur of the structures. Some theories suggest fluting also added a subtle degree of compressive strength, although its primary role was visual.

- Truss Systems and Timber Roofs: While stone provided the enduring shell of their buildings, timber played a crucial role in roofing. Greek engineers developed sophisticated timber truss systems to span wide spaces, reducing the need for numerous internal supports and creating expansive interiors. These trusses employed triangulated frames, a fundamental principle of structural engineering that distributes loads efficiently. The roof tiles, typically made of terracotta, were then laid over these timber frames. The weight of these tiles, combined with the often steep pitches, necessitated robust timber frameworks to prevent collapse.

- Foundation Techniques: Before any visible structure was erected, meticulous attention was paid to the foundations. Greek builders excavated deep trenches, often down to bedrock, to create stable bases for their temples and public buildings. They utilized stepped foundations (stereobates and stylobates) which spread the immense weight of the masonry over a larger area, reducing pressure on the underlying soil. The precision with which these foundation layers were laid is a testament to their engineering prowess, ensuring the long-term stability of structures that have endured for millennia.

Ancient Greek mechanical engineering is a fascinating subject that highlights the ingenuity and creativity of early civilizations. One related article that delves into this topic is titled “The Innovations of Ancient Greek Mechanical Engineering,” which explores the various inventions and mechanisms developed during that era. To learn more about these remarkable advancements, you can read the article here: The Innovations of Ancient Greek Mechanical Engineering.

Hydraulic Engineering: Mastering Water Resources

Beyond their monumental edifices, the ancient Greeks exhibited remarkable ingenuity in managing and manipulating water, a vital resource for agriculture, sanitation, and urban living. Their hydraulic engineering projects, though often less visible than their temples, were equally transformative.

Aqueducts and Water Supply Systems: The Lifelines of Cities

Ensuring a reliable supply of fresh water was a critical challenge for growing Greek cities. Their solutions demonstrate an advanced understanding of hydrology and civil engineering principles.

- Gravity-Fed Systems: The Greeks understood that water flows downhill. Their aqueducts were meticulously engineered, often over many kilometers, to maintain a gradual, consistent slope, allowing water to flow by gravity from distant springs or rivers to urban centers. This required precise surveying and leveling techniques, often using rudimentary but effective tools such as chorobates (a level with a water trough) and groma (a sighting instrument). The gradients, though subtle, were crucial for maintaining flow velocity without causing excessive erosion or stagnation.

- Tunnels (Qanat and Siphons): Where geographical obstacles prevented continuous surface channels, Greek engineers resorted to tunnels. The Eupalinos Tunnel on Samos, for example, is a testament to their tunneling expertise. It was excavated simultaneously from both ends, meeting remarkably accurately in the middle, a feat that required sophisticated surveying and planning. They also employed inverted siphons, particularly in regions with valleys, where water was channeled downwards in pressurized pipes before rising again on the other side, utilizing the principle of communicating vessels. This allowed them to cross depressions without expensive and vulnerable bridge structures.

- Reservoirs and Distribution: Once water reached the city, it was often collected in large reservoirs or cisterns, many of which were elaborate underground structures designed to minimize evaporation and maintain water quality. From these reservoirs, a network of terracotta or lead pipes distributed water to public fountains, baths, and private residences. The use of lead, while effective for its malleability and durability, also presented health risks, a fact not fully understood at the time.

Drainage and Sanitation: Pioneering Public Health

Effective drainage systems were vital for urban hygiene and flood control. The Greeks, understanding the link between stagnant water and disease, incorporated sophisticated drainage into their urban planning.

- Underground Sewers: Many Greek cities possessed rudimentary yet effective underground sewer systems, particularly in public areas like the Agora. These channels, often lined with stone, collected rainwater and wastewater, diverting it away from residential areas and into rivers or the sea. The gradient of these sewers was carefully calculated to ensure continuous flow and prevent blockages.

- Public Latrines: While not as widespread or luxurious as Roman baths, Greek cities did feature public latrines, indicating a societal awareness of sanitation. These facilities often utilized continuous flushing water, sometimes fed by overflow from fountains, to carry waste away. The design principles were simple yet effective, aiming to minimize odors and disease transmission.

- Stormwater Management: Beyond sanitary waste, Greek engineers also tackled stormwater management. They designed paved streets and public squares with gentle slopes, channeling rainwater into drainage channels and ultimately away from built-up areas. This protected foundations from water damage and reduced the risk of flash flooding during heavy rainfall.

Military Engineering: Fortifications and Sieges

The frequent conflicts between Greek city-states necessitated robust defensive structures and offensive siege technologies. Greek military engineers were adept at both.

Fortifications: Walls, Towers, and Gates

The construction of fortifications was a primary concern for every city-state. These monumental defensive works were designed to withstand prolonged sieges and protect inhabitants.

- Cyclopean Masonry and Polygonal Walls: Early Greek fortifications, often termed “Cyclopean” for their massive, irregular stonework, demonstrated an understanding of creating impenetrable barriers. Later, polygonal masonry, where precisely cut, multi-sided blocks fitted together without mortar, provided exceptional strength and resistance to undermining. These walls were often many meters thick, making them highly resistant to battering rams and other siege engines.

- Towers and Parapets: Defensive walls were punctuated by projecting towers, allowing defenders to unleash flanking fire upon attackers approaching the main wall. These towers often incorporated parapets, crenellated battlements that provided cover for archers and slingers while allowing them to engage the enemy. Walkways along the top of the walls enabled rapid troop movement and supply lines during a siege.

- Fortified Gates and Entrances: The weakest points in any defensive line were the gates. Greek engineers designed elaborate gate complexes, often with multiple doors, inner courtyards (enceintes), and projecting towers to create killing zones where attackers could be ambushed from multiple angles. Portcullises and heavy wooden doors, reinforced with metal, provided formidable barriers.

Siege Warfare: Ingenuity in Attack and Defense

While impressive at defense, Greek engineers also developed sophisticated tools for offense.

- Battering Rams and Siege Towers: The development of the battering ram, often encased in a protective shed to shield its operators, was a crucial innovation for breaching city walls. Siege towers, multi-storied mobile structures, allowed attackers to reach the top of enemy walls, facilitating direct assaults and enabling archers to fire down into the city. These were often meticulously constructed on-site.

- Catapults and Ballistae (Early Forms): Although truly powerful siege engines became more common in the Hellenistic period, early forms of torsion-powered catapults and ballistae, designed to hurl large stones or massive arrows, saw increasing use. These machines, relying on the stored energy of twisted ropes, represented a significant step in the application of mechanical principles to warfare, allowing for greater range and destructive power than handheld weapons.

- Counter-Mining and Sapping: Defenders were not without their own engineering responses. Counter-mining involved digging tunnels beneath approaching siege engines or enemy positions to collapse them. Sapping, the undermining of enemy walls, was also a common tactic, often involving the strategic removal of foundation stones to cause a section of the wall to collapse.

Maritime Engineering: Harbors and Naval Power

As a thalassocracy (sea power), the Greeks invested significantly in maritime infrastructure, which was crucial for trade, communication, and naval dominance.

Harbors and Breakwaters: Protecting the Fleet

Greek harbors were more than just natural inlets; they were carefully engineered to provide safe anchorage and facilitate shipping.

- Molehills and Breakwaters: To create protected harbors in exposed coastal areas, Greek engineers constructed massive breakwaters, extending out into the sea. These structures, often built from large, unmortared blocks of stone (opus caementicium – a rudimentary form of concrete – was also used in some regions, though more commonly associated with Rome), dissipated the energy of incoming waves, creating calm water within the harbor. The construction of these underwater foundations required considerable skill and knowledge of marine conditions.

- Docks and Quays: Within the sheltered harbors, elaborate dock systems and quays were built to facilitate the loading and unloading of cargo and the mooring of ships. These often involved timber or stone structures, designed to withstand the constant ebb and flow of tides and the impact of vessels. Slipways were also constructed for the launching and hauling out of ships for maintenance.

- Lighthouses (Early Forms): While the monumental Pharos of Alexandria came later, early forms of navigation aids, such as fire beacons on prominent headlands or at harbor entrances, were used to guide ships at night, representing the precursors to the modern lighthouse.

Triremes: The Apex of Naval Design

The Greek trireme, a warship propelled by three banks of oars, was a peak of ancient naval engineering, embodying speed, maneuverability, and destructive power.

- Hull Design and Construction: The trireme’s hull was designed for shallow draft and exceptional speed. Constructed from timber, often pine or fir, the hull was lightweight yet strong. The curved lines of the hull and the finely tuned ratio of length to beam were not accidental but the result of centuries of shipbuilding experience and empirical observation. The construction involved a complex process of assembling frames and planking, often with meticulous waterproofing techniques using pitch and tar.

- Oar Systems and Propulsion: The defining feature of the trireme was its three banks of oars. This sophisticated arrangement of oarsmen, precisely coordinated, allowed for bursts of incredible speed, essential for ramming enemy vessels. The placement of the oars and the ergomonics of the rowing positions were optimized for maximum efficiency and endurance. Specialized mechanisms allowed for the precise entry and exit of oars from the water.

- Tactical Innovations (The Ram): The bronze-sheathed ram, projecting from the bow of the trireme, was its primary weapon. The design of the ram, its placement on the hull, and the trireme’s ability to achieve high speeds enabled it to punch through the hulls of enemy ships, incapacitating or sinking them. This combination of speed, maneuverability, and destructive power made the trireme a dominant force in ancient naval warfare.

Ancient Greek mechanical engineering is a fascinating subject that showcases the ingenuity of early inventors and their contributions to technology. One notable example is the Antikythera mechanism, often considered the world’s first analog computer, which was used to predict astronomical positions and eclipses. For those interested in exploring more about the remarkable achievements of ancient civilizations in engineering, you can read a related article that delves into various inventions and their impacts on society. This insightful piece can be found here.

Early Robotics and Automation: The Seeds of Mechanization

| Device | Inventor | Approximate Date | Function | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antikythera Mechanism | Unknown | Circa 100 BCE | Astronomical calculator to predict celestial events | Earliest known analog computer |

| Automata (Mechanical Birds) | Hero of Alexandria | 1st Century CE | Self-operating mechanical devices powered by steam or water | Early example of robotics and pneumatics |

| Water Screw (Archimedes’ Screw) | Archimedes | 3rd Century BCE | Device to raise water for irrigation | Efficient water lifting technology still used today |

| Catapult | Unknown (improved by Dionysius of Alexandria) | 4th Century BCE | Military siege engine to launch projectiles | Advanced ancient warfare technology |

| Odometer | Archimedes (attributed) | 3rd Century BCE | Device to measure distance traveled by a vehicle | Early mechanical measurement instrument |

Beyond the large-scale infrastructure projects, the Greeks also demonstrated an early fascination with automation and mechanical devices, often for entertainment or religious purposes, foreshadowing later developments in robotics.

Automata and Mechanical Toys: Heron of Alexandria’s Legacy

While much of the evidence for advanced automata comes from the later Hellenistic period (e.g., Heron of Alexandria), the foundations for such devices were laid in earlier Greek fascination with mechanics.

- Archytas’ Pigeon: Archytas of Tarentum, a contemporary of Plato in the 4th century BCE, is credited with constructing a mechanical wooden pigeon capable of flight, purportedly propelled by steam or compressed air. While the precise details are lost, this account highlights an early Greek interest in applying mechanical principles to create animated objects.

- Temple Automata (Early Forms): There are historical accounts and archaeological suggestions of early automata used in temples. These might have included doors that opened automatically, statues that moved, or figures that poured libations, often utilizing pneumatic or hydraulic principles. These were often designed to inspire awe and reinforce religious beliefs.

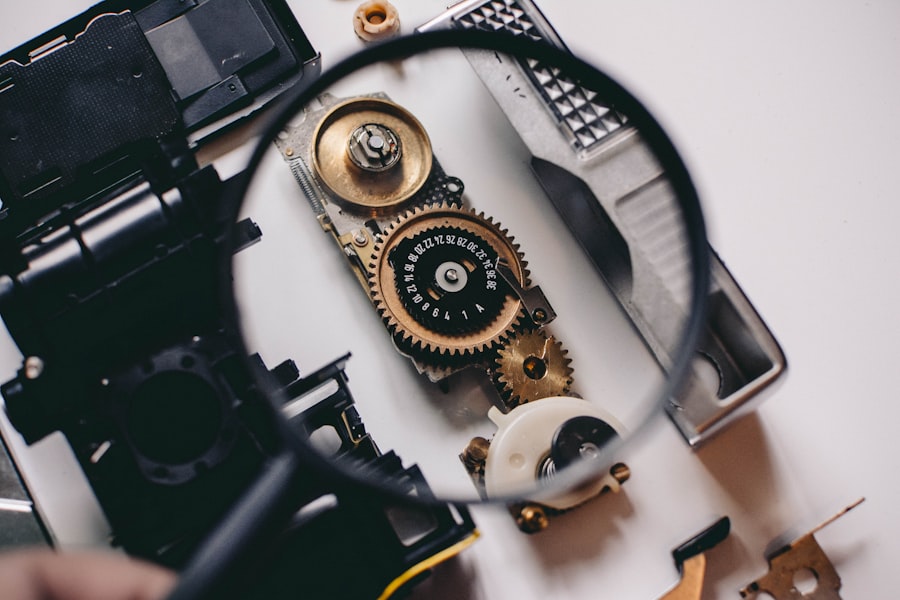

- Clepsydra (Water Clocks) and Astronomical Instruments: Water clocks, or clepsydra, were not merely timekeeping devices but early forms of hydraulic automation. They often incorporated intricate mechanisms to regulate water flow or to display time, sometimes even with moving figures or chimes. Astronomical instruments like the Antikythera Mechanism, though dating to the Hellenistic period, represent the pinnacle of complex gearwork and mechanical computation, demonstrating a deep understanding of interlocking systems and precision manufacturing. These devices laid the groundwork for future advancements in mechanical engineering.

Legacy and Impact: Shaping the Future

The engineering achievements of the ancient Greeks were not confined to their own time. They constituted a profound legacy that continued to influence subsequent civilizations and laid fundamental groundwork for modern engineering principles.

Influence on Roman Engineering: Adopting and Adapting

The Romans, often celebrated for their engineering prowess, readily adopted and adapted many Greek techniques.

- Aqueduct Systems: Roman aqueducts, while often larger and more numerous, built upon the fundamental gravity-fed principles and tunneling techniques pioneered by the Greeks.

- Architectural Elements: Roman temples and public buildings extensively employed Greek architectural orders, albeit often with their own stylistic adaptations and a greater emphasis on concrete.

- Military Engineering: Roman siege engines and fortifications evolved from Greek precedents, incorporating and refining technologies like siege towers and battering rams.

Fundamental Principles: Enduring Lessons

Beyond direct adoption, Greek engineering bequeathed enduring principles of design and construction.

- The Golden Ratio and Proportion: While often attributed to aesthetics, the application of harmonious proportions, like the Golden Ratio, in their architecture often had underlying structural benefits too, contributing to both stability and visual balance.

- Leverage and Mechanical Advantage: Their extensive use of levers and rollers for moving heavy objects demonstrated a deep intuitive, if not formalized, understanding of mechanical advantage, a cornerstone of engineering.

- Precision and Standardization: The remarkable precision in stone cutting, the fitting of column drums, and the consistent gradients of their hydraulic systems all point to an early form of standardization and quality control in construction, vital for large-scale projects.

The meticulous examination of Greek engineering reveals a civilization that, far from being solely devoted to abstract thought, possessed a robust practical intelligence and an impressive capacity for material innovation. Their temples, aqueducts, fortifications, and even their early mechanical devices serve as enduring testaments to their ingenuity, demonstrating how fundamental scientific understanding, combined with resourceful application, could profoundly shape the physical world and lay the foundations for future technological advancements. The secrets unlocked from their ancient structures continue to inform and inspire engineers today, reminding us that the timeless principles of design and construction endure across millennia.

STOP: Why They Erased 50 Impossible Inventions From Your Textbooks

FAQs

What were some key inventions of ancient Greek mechanical engineering?

Ancient Greek mechanical engineering included inventions such as the water screw (attributed to Archimedes), early automata, complex catapults, and various types of cranes and hoists used in construction and warfare.

Who were prominent figures in ancient Greek mechanical engineering?

Notable figures include Archimedes, known for his work on levers, pulleys, and the Archimedean screw; Hero of Alexandria, famous for his automata and early steam engine concepts; and Ctesibius, who contributed to the development of water clocks and pneumatic devices.

How did ancient Greeks apply mechanical engineering in daily life?

Mechanical engineering was applied in water management systems, such as aqueducts and pumps, in construction machinery like cranes, in military technology including catapults and siege engines, and in entertainment through mechanical theaters and automata.

What materials did ancient Greek engineers commonly use?

Ancient Greek engineers primarily used materials such as wood, bronze, iron, and stone. Bronze and iron were used for tools and mechanical parts, while wood was common for structural components and moving parts.

How did ancient Greek mechanical engineering influence later civilizations?

Ancient Greek mechanical engineering laid foundational principles in mechanics and automation that influenced Roman engineering and later the Renaissance. Their inventions and theoretical work were studied and expanded upon, contributing to the development of modern engineering and technology.