Before the hammering and the hissing of cooling quenchant became synonymous with civilization, metal lay dormant, a captive within the earth’s crust. The journey of humanity from stone to steel was not a sudden leap, but a gradual unfolding, a series of discoveries that fundamentally reshaped societies and fueled innovation. While medieval metallurgy represents a significant period of refinement, understanding the bedrock of ancient metallurgical advancements provides crucial context for the subsequent evolution of metalworking. The ancient world, a tapestry woven with the threads of ingenuity, laid the foundation upon which all later metallic achievements would be built.

The Spark of Discovery: Unearthing the First Metals

The initial encounter with metals was likely accidental. Nuggets of native copper, shimmering against the dull backdrop of rock, would have caught the eye. These malleable curiosities could be hammered into simple tools and ornaments, a process known as cold working. This marked the very first steps, a tentative handshake with a material far more versatile than stone.

Native Copper: The Genesis of Metallic Artifice

- Observation and Manipulation: Early humans, observing the pliability of native copper, learned to shape it through repeated hammering. This rudimentary technique, while limited in its scope, yielded beads, awls, and small projectile points. The inherent limitations of cold working meant that complex shapes or hardened edges were largely unattainable.

- Geographical Prevalence: The widespread availability of native copper in certain regions, such as the Middle East and parts of Europe, facilitated its early adoption. Societies fortunate enough to have accessible deposits of this precious metal could begin to experiment and innovate.

The Crucible of Heat: The Advent of Smelting

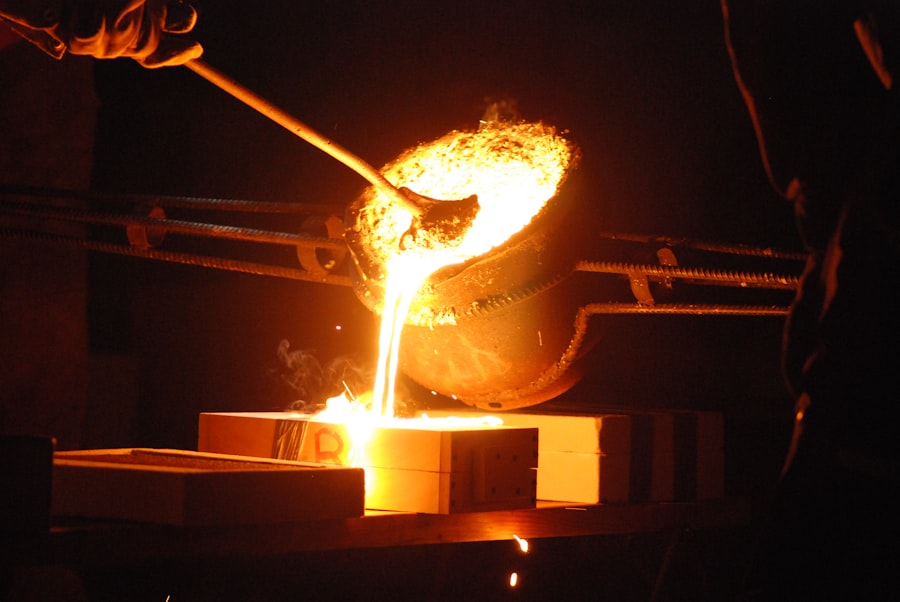

The true revolution began with the understanding that heat could transform raw ore into molten metal. This leap from cold working to smelting, the process of extracting metal from its ore using heat, was a monumental discovery, akin to humanity learning to harness fire itself. This was not a simple matter of applying a flame; it required a deep understanding of materials and controlled heating. The development of primitive furnaces, often simple pits lined with clay, marked the dawn of true metallurgy.

Early Furnace Designs: Hearth to Kiln

- Pit Furnaces: The earliest smelting operations likely utilized simple pit furnaces, where ore and fuel were placed in a dug depression and ignited. While basic, these provided enough heat to reduce certain metal oxides.

- Clay-Lined Structures: The refinement of furnace design saw the introduction of clay linings. This provided better insulation, allowing for higher temperatures to be reached and sustained, crucial for efficient metal extraction. These proto-kilns were the cradles in which molten metal was first born.

Fueling the Fire: The Importance of Charcoal

- Carbon as a Reductant: The effectiveness of early smelting relied heavily on the use of charcoal as fuel. Charcoal, a carbon-rich material, not only provided heat but also acted as a chemical reductant, stripping oxygen away from the metal oxides in the ore. This chemical interaction was the secret ingredient that unlocked the metallic potential.

- Controlled Combustion: Achieving the right balance of fuel and air was critical for successful smelting. Early metallurgists learned, through trial and error, to control airflow into their furnaces, a rudimentary form of early process engineering.

The Transformation of Ore: From Rock to Metal

- Reducing Metal Oxides: The core principle of smelting involves heating metal oxides in the presence of a reducing agent (like carbon) to a temperature above the metal’s melting point. This process liberates the pure metal.

- Slag Formation: Unwanted impurities in the ore would melt and separate from the molten metal, forming a glassy substance known as slag. The ability to separate and discard slag was another crucial practical advancement.

Ancient metallurgy has often been overshadowed by the advancements seen during the medieval period, yet recent studies reveal that certain ancient civilizations possessed techniques that were remarkably sophisticated. For instance, the article found at this link discusses how the Egyptians and Mesopotamians developed advanced smelting processes and alloying techniques that allowed them to create durable tools and weapons long before the medieval era. These innovations not only highlight the ingenuity of ancient cultures but also set the foundation for future metallurgical advancements.

The Bronze Age: A Symphony of Alloys

The discovery and widespread use of bronze represented a quantum leap in material science. This alloy, typically comprising copper and tin, possessed properties far superior to pure copper. Bronze was harder, more durable, and could hold a sharper edge, ushering in an era of more sophisticated tools, weapons, and even intricate artwork. This was the world’s first engineered material, a deliberate combination to achieve desired performance.

The Alchemy of Alloys: Copper Meets Tin

The precise moment and location of the first bronze alloy creation remain a subject of ongoing archeological investigation. However, the gradual confluence of copper and tin sources, coupled with the growing understanding of heat manipulation, led to this transformative discovery. Accidental alloying, perhaps by placing copper in a furnace containing tin-bearing rocks, may have been the initial catalyst.

Accidental Discovery and Intentional Replication: From Chance to Craft

- The Serendipitous Mix: It is plausible that early copper smelting occurred in areas where tin ore was also present or processed. The proximity of these materials in furnaces could have led to accidental alloying, with the resulting bronze exhibiting superior properties.

- Recognizing Superiority: Once the benefits of this new material were observed – its increased hardness and better durability – deliberate experimentation likely followed. Metallurgists began to actively seek out and combine copper with tin in controlled proportions.

The Optimal Blend: Proportions and Properties

- Varying Tin Content: The properties of bronze can be finely tuned by adjusting the ratio of copper to tin. Higher tin content generally leads to a harder but more brittle alloy, while lower tin content results in a tougher, more ductile metal.

- Beyond Pure Copper: Bronze’s superiority over pure copper was evident. The ability to cast more intricate shapes and create weapons and tools that retained their edge for longer periods revolutionized warfare, agriculture, and craftsmanship.

The Bronze Age Arsenal: Tools and Weapons of Distinction

The advent of bronze had profound implications for societal development. Warfare became more lethal, agricultural production more efficient, and elaborate art and architecture more achievable. The widespread adoption of bronze artifacts signifies a major turning point in human history.

The Sword of Damocles: Military Might Reimagined

- Sharper Edges, Deeper Wounds: Bronze swords and spearheads could be sharpened to a degree impossible with copper. This gave an undeniable advantage to bronze-wielding armies, fundamentally altering the dynamics of conflict.

- Mass Production of Arms: As tin sources became more accessible and smelting techniques improved, the mass production of bronze weapons became feasible, enabling larger armies and more ambitious conquests.

The Plowshare’s Promise: Agricultural Revolution

- Durable and Effective Tools: Bronze plows could till harder soils more effectively than their stone or copper predecessors, leading to increased agricultural yields and supporting larger populations.

- Expanding Cultivated Lands: The ability to work the land more efficiently contributed to the expansion of arable land and the development of more complex settlements.

The Artisan’s Delight: Craftsmanship and Ornamentation

- Intricate Casting: Bronze’s lower melting point compared to iron made it more amenable to casting. This allowed for the creation of highly detailed sculptures, jewelry, and decorative objects, showcasing the artistic capabilities of Bronze Age societies.

- Lost-Wax Casting: A sophisticated technique known as the lost-wax casting method, which was mastered during the Bronze Age, enabled the creation of complex, hollow objects with exceptional precision.

The Iron Age: Forging the Future

The transition to the Iron Age was another pivotal moment, albeit one that unfolded more gradually than the Bronze Age. Iron ore was far more abundant than copper and tin, promising a more democratized access to metal. However, iron’s higher melting point presented significant challenges, requiring different smelting techniques and a deeper understanding of heat control and carbon’s role in hardening. This was like learning to fly after mastering walking; a new realm of possibilities opened.

The Challenge of the Furnace: Taming the Fiery Beast

Unlike bronze, which melts at relatively low temperatures, iron requires substantially higher heat for smelting. This necessitated the development of more advanced furnaces capable of reaching and sustaining these extreme temperatures. Early iron-making was a far more arduous and less predictable process.

Blast Furnaces: A Breath of New Life

- Increased Airflow and Temperature: The development of primitive blast furnaces, often incorporating bellows or other mechanisms to force air into the combustion chamber, was crucial. This increased oxygen supply fueled more intense fires, reaching the temperatures needed to reduce iron oxides.

- The Dawn of Bloomery Furnaces: The primary technology associated with early iron smelting was the bloomery furnace. This type of furnace produced a spongy mass of iron, known as a bloom, mixed with slag. Separating the iron from the slag was a labor-intensive post-smelting process.

Carbon’s Crucial Role: From Soft Iron to Hard Steel

- Carburization: Pure iron, when smelted, is relatively soft. The key to its utility lay in introducing carbon into its structure, a process known as carburization. This could occur during the smelting process or through subsequent heating and hammering in a carbon-rich environment.

- The Making of Steel: The controlled introduction of carbon transforms iron into steel, an alloy with vastly superior strength and hardness. Understanding the relationship between carbon content and material properties was a profound insight.

From Bloom to Blade: Crafting with Iron

The ability to work with iron, despite its initial challenges, unlocked a new era of tool and weapon production. Iron implements were more durable and could hold a sharper edge for longer than bronze, gradually displacing their predecessors.

The Ploughshares’ Renewed Promise: Agricultural Expansion

- Stronger and More Durable Tools: Iron plows could break through tougher soils and were far more resistant to wear and tear than bronze implements. This enabled more extensive agricultural practices and the cultivation of previously unmanageable lands.

- Increased Productivity: The efficiency gains from iron agricultural tools directly contributed to higher food yields and the support of larger, more complex societies.

The Warrior’s Edge: Dominance on the Battlefield

- Superior Weapons: Iron swords, spearheads, and armor offered a significant technological advantage on the battlefield over bronze. Their durability and ability to maintain a sharp edge provided a decisive edge in combat.

- Democratization of Warfare: The wider availability of iron ore meant that iron weapons could be produced in greater numbers, potentially leveling the playing field and allowing for larger, more broadly equipped armies.

The Blacksmith’s Art: Shaping the Future

- Forge-Welding: The mastery of forge-welding, the process of joining pieces of iron or steel by heating them to a high temperature and hammering them together, was essential for creating complex tools and weapons.

- Tempering and Annealing: Understanding tempering (hardening by rapid cooling) and annealing (softening by controlled heating and cooling) allowed blacksmiths to fine-tune the properties of iron and steel, creating materials suited for specific purposes.

Beyond the Basics: Sophistication in Ancient Metallurgy

While the discovery and development of copper, bronze, and iron represent the primary advancements, ancient metallurgists explored other metals and developed sophisticated techniques for their extraction and refinement. Their understanding was not confined to the most common metals; they possessed a broader knowledge base, often shrouded in the mists of time.

Precious Metals and Their Allures: Gold, Silver, and Their Applications

The allure of gold and silver was recognized from humanity’s earliest encounters with metal. Their distinctive appearance, resistance to corrosion, and malleability made them ideal for ornamentation, currency, and religious artifacts. Ancient peoples developed specialized techniques to extract and work these precious materials.

The Gleam of Gold: A Symbol of Wealth and Power

- Native Gold and Alluvial Deposits: Gold, often found in its native, unalloyed state, was readily accessible in alluvial deposits (riverbeds). Early methods involved panning and simple gravity separation to collect the gleaming nuggets.

- Beating and Filigree: Gold’s exceptional malleability allowed it to be hammered into incredibly thin sheets (gold leaf) and intricately worked into delicate filigree designs, demonstrating an astonishing level of artistic and technical skill.

The Shine of Silver: Currency and Craftsmanship

- Extraction from Ores: Silver was typically extracted from ores such as argentiferous galena (lead sulfide containing silver). Smelting and cupellation (a refining process that removes base metals) were employed to isolate the silver.

- Coinage and Utensils: Silver’s use as a medium of exchange (coinage) and for crafting high-quality vessels and decorative items became widespread, indicating a sophisticated understanding of its economic and aesthetic value.

Early Alloying Experiments: Beyond Bronze

While bronze was the most significant alloy of antiquity, evidence suggests experimentation with other metallic combinations. These ventures, though perhaps less widespread or successful than bronze production, demonstrate a nascent understanding of how mixed metals could yield unique properties.

Electrum: The Natural Alloy of Gold and Silver

- Prevalence in Nature: Electrum, a naturally occurring alloy of gold and silver, was found in certain regions and used in early coinage and jewelry. Its discovery may have spurred further deliberate alloying efforts.

- Varied Composition: The relative proportions of gold and silver in electrum varied, leading to slight differences in color and properties, an early observation of how composition impacts material characteristics.

Lead and Pewter: Early Forays into Other Alloys

- Lead’s Malleability and Low Melting Point: Lead was used in various applications, including pipes and pigments. Its low melting point made it easy to cast, though its toxicity was not understood.

- Pewter: A Tin-Lead Alloy: The combination of tin and lead to create pewter provided a more durable and less expensive alternative to silver for tableware and decorative items. This represented a practical step towards engineered alloys.

Ancient metallurgy has often been overshadowed by the advancements of the medieval period, yet recent studies reveal that certain ancient civilizations possessed techniques that were surprisingly sophisticated. For instance, the use of high-temperature furnaces and the alloying of metals such as bronze and gold in ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia demonstrate a level of metallurgical knowledge that rivals later developments. If you’re interested in exploring this topic further, you can read more about these fascinating techniques in this related article on ancient metallurgy found here.

The Legacy of Ancient Metallurgy: Echoes in Modern Technology

| Aspect | Ancient Metallurgy | Medieval Metallurgy | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Material Purity | High purity bronze and iron alloys achieved through advanced smelting techniques | Variable purity, often lower due to inconsistent smelting methods | Ancient civilizations like the Hittites mastered iron smelting earlier |

| Alloy Complexity | Use of complex alloys such as arsenical bronze and early steel variants | Predominantly carbon steel with less experimentation in alloying | Ancient metallurgists experimented with alloying for specific properties |

| Smelting Temperature Control | Advanced furnace designs allowing higher and more consistent temperatures | Improved but often less consistent temperature control | Ancient furnaces like bloomery and crucible furnaces were highly efficient |

| Metalworking Techniques | Precision casting, lost-wax casting, and early forging techniques | More widespread forging and tempering but less precision casting | Ancient artisans produced intricate metal objects with fine detail |

| Production Scale | Specialized workshops producing high-quality metal goods | Mass production for warfare and agriculture but often lower quality | Ancient metallurgy focused on quality and innovation |

The advancements made in ancient metallurgy were not mere historical curiosities; they formed the essential bedrock upon which all subsequent technological development has been built. The principles of smelting, alloying, and controlled heat treatment, honed over millennia in ancient workshops, continue to inform modern metallurgical practices. The metallurgists of old, though lacking our advanced scientific instruments, possessed an empirical wisdom that allowed them to unlock the potential of the earth’s metallic treasure.

The Foundation of Industrial Revolutions

The knowledge and techniques developed by ancient metallurgists directly paved the way for future innovations. Without the mastery of smelting iron, the Industrial Revolution, with its steam engines and burgeoning factories, would have been impossible. The principles of large-scale production and material engineering find their roots in these ancient endeavors.

From Bloomery to Blast Furnace: A Continuous Evolution

- Scaling Up Production: The incremental improvements in furnace design, from the simple bloomery to more sophisticated blast furnaces, represent a continuous trajectory of increasing efficiency and scale. This ongoing pursuit of better production methods is a hallmark of technological progress.

- The Unseen Hand of Innovation: Each refinement in ancient metallurgy, whether it was a slightly better way to control airflow or a more effective method of purifying ore, added another brick to the edifice of human technological capability.

The Material Basis of Civilization

- Tools, Infrastructure, and Defense: The prevalence of metal tools, from agricultural implements to construction materials and weaponry, underscores the fundamental role of metallurgy in shaping human civilization. The very fabric of our settlements and the nature of our defense were dictated by the metals we could produce.

- Trade and Economic Development: The extraction and trade of metals, particularly precious metals and critical resources like tin, fueled economic development and fostered interdependence between different cultures.

The Spirit of Innovation: Enduring Principles of Metallurgy

The ingenuity displayed by ancient metallurgists continues to inspire. Their patient experimentation, their keen observation of material properties, and their iterative approach to problem-solving are timeless principles that guide scientific and engineering endeavors today. The echoes of their hammers still resonate in the hum of modern foundries.

Empirical Knowledge and Scientific Inquiry

- Observation-Driven Discovery: The bulk of ancient metallurgical knowledge was acquired through meticulous observation and practical experimentation. While not based on codified scientific theory, this empirical approach yielded remarkably effective results.

- The Bridge to Modern Science: This legacy of empirical discovery laid the groundwork for the development of scientific metallurgy, where theoretical understanding now complements and accelerates practical application.

A Global Tapestry of Metallurgical Traditions

- Independent Innovations: Similar metallurgical techniques and knowledge emerged independently in various parts of the world, demonstrating the universal human drive to understand and manipulate materials. This global diffusion of innovation highlights a shared human ingenuity.

- Cross-Cultural Exchange: The Silk Road and other ancient trade routes facilitated the exchange of metallurgical knowledge and techniques between different civilizations, fostering a cross-pollination of ideas that accelerated progress.

The ancient world, with its forge fires burning bright, was far more than a prelude to the medieval era; it was the very germination of our metallic age. The artisans and smiths of antiquity, through a combination of accident, observation, and persistent effort, transformed raw materials into the tools and treasures that built civilizations. Their legacy, etched in bronze and tempered in iron, continues to shape our world, a testament to the enduring power of human ingenuity.

STOP: Why They Erased 50 Impossible Inventions From Your Textbooks

FAQs

What is ancient metallurgy?

Ancient metallurgy refers to the techniques and processes used by early civilizations to extract and work with metals such as copper, bronze, and iron. These methods date back thousands of years and include smelting, alloying, and forging.

How was ancient metallurgy more advanced than medieval metallurgy?

Ancient metallurgy was sometimes more advanced in terms of the quality and composition of metal artifacts. For example, some ancient cultures developed sophisticated alloying techniques and high-temperature furnaces that produced metals with superior strength and durability compared to certain medieval counterparts.

Which ancient civilizations were known for advanced metallurgy?

Civilizations such as the Egyptians, Hittites, Chinese, and Indians were known for their advanced metallurgical skills. They developed early smelting techniques, created complex alloys like bronze and Damascus steel, and produced finely crafted metal tools and weapons.

What metals were commonly used in ancient metallurgy?

Common metals used in ancient metallurgy included copper, tin, bronze (an alloy of copper and tin), gold, silver, and later iron. Each metal required specific techniques for extraction and working, which ancient metallurgists mastered over time.

How did ancient metallurgical techniques influence later periods?

Ancient metallurgical knowledge laid the foundation for later technological developments. Techniques such as alloying and high-temperature smelting were passed down and refined during the medieval period, influencing the production of weapons, tools, and architectural materials.