The nocturnal sky has long captivated humanity, serving not only as a source of wonder but also as a practical tool for navigation, timekeeping, and understanding the universe. Ancient civilizations, lacking modern instruments, developed sophisticated methods to observe and record celestial phenomena. These observations, meticulously etched into stone, painted on cave walls, or documented in written texts, represent a collective endeavor to chart the cosmos. This article explores the rich tapestry of ancient star maps and celestial calendars, examining their construction, purpose, and enduring legacy.

The earliest compelling evidence of astronomical awareness can be traced back to the Upper Paleolithic period. These initial engagements with the heavens were primarily observational, but even at this nascent stage, a clear intent to record and understand celestial patterns emerges.

Paleolithic Star Charts: Decoding Prehistoric Astronomy

Archaeological discoveries have unearthed artifacts suggesting a surprisingly early understanding of stellar cycles. The Nebra Sky Disk, discovered in Germany, provides a prominent example. Dated to approximately 1600 BCE, this bronze disk features gold appliqués depicting the sun or a full moon, a lunar crescent, and stars, including a cluster interpreted as the Pleiades. Its design suggests a sophisticated understanding of their positions relative to each other and their potential use in calendrical calculations. This disk is not merely a decorative object; it functions as a portable astronomical instrument, reflecting the deep engagement of its creators with the celestial sphere.

Similarly, interpretations of cave paintings, such as those found at Lascaux in France, suggest depictions of star patterns. While some academic debate persists regarding their definitive astronomical nature, these artistic representations offer compelling hypotheses regarding the early human fascination with constellations and their potential storytelling or mythological significance. These early “star charts,” though rudimentary by modern standards, represent a fundamental step in humanity’s quest to map and comprehend the night sky. They are the seeds from which later, more complex astronomical systems would blossom.

Megalithic Observatories: Stones as Timekeepers

Across the globe, megalithic structures stand as testament to ancient peoples’ advanced astronomical knowledge. These monumental constructions, often comprising massive stones arranged in precise alignments, operated as sophisticated observatories. Their architectural designs frequently align with solstices, equinoxes, and specific lunar phases, demonstrating a meticulous understanding of celestial mechanics.

- Stonehenge and its alignments: Stonehenge, in England, is perhaps the most famous example. Its primary axis aligns with the summer solstice sunrise and the winter solstice sunset. Further alignments point to lunar extremes, indicating a dual focus on both solar and lunar cycles for calendrical purposes. The sheer precision required to construct such a complex astronomical instrument without modern tools is remarkable. The arrangement of the sarsen stones and bluestones served as a colossal calendar, marking significant temporal points in the agricultural and ritualistic year.

- Newgrange and its solar illumination: Newgrange, a passage tomb in Ireland, offers another compelling example. During the winter solstice sunrise, a narrow beam of light penetrates the long passage, illuminating the central chamber. This deliberate architectural feature signifies the importance of the solstice in the spiritual and calendrical practices of its builders. It is a profound demonstration of the integration of astronomical knowledge with religious and cultural beliefs.

- Carnac Stones and their complex arrangements: The Carnac Stones in Brittany, France, consist of thousands of megaliths arranged in rows and circles. While their precise astronomical function remains a subject of ongoing research, many theories suggest alignments with celestial events and their use as a form of astronomical calculator or calendar. These structures exemplify a widespread ancient practice of integrating astronomical knowledge into monumental architecture, reflecting a communal scientific endeavor.

These megalithic observatories were not simply passive viewing platforms; they were active instruments for tracking celestial movements, serving crucial functions in agricultural planning, religious ceremonies, and societal organization. They represent mankind’s early attempts to “program” the landscape to mirror the heavens.

Ancient star maps and celestial calendars have long fascinated historians and astronomers alike, revealing how early civilizations navigated and understood the cosmos. For those interested in exploring this topic further, a related article can be found at this link, which delves into the intricate designs and purposes of these celestial tools used by our ancestors.

The Development of Structured Star Maps and Calendars

As societies grew more complex, so too did their astronomical understanding. The casual observations of earlier periods evolved into codified systems, with specialized individuals dedicated to celestial study.

Mesopotamian and Egyptian Contributions: Foundations of Astrology and Calendar Systems

The civilizations of Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt made fundamental contributions to the study of the stars, laying groundwork for future astronomical and astrological developments. Their textual records provide invaluable insights into their sophisticated understanding of the cosmos.

- Zodiacal system and celestial omens: Mesopotamian astronomers, particularly the Babylonians, developed a sophisticated zodiacal system. They divided the ecliptic into twelve segments, each associated with a specific constellation. This system was not merely for mapping the sky but also for predicting events and interpreting omens. Their detailed astronomical tablets, such as the Enūma Anu Enlil, meticulously record celestial phenomena and their perceived terrestrial implications, intertwining astronomy with divination and statecraft. The predictable cycles of the heavenly bodies were seen as reflections of divine will, offering guidance to rulers and ordinary people alike.

- Nile calendar and stellar alignments: Ancient Egyptians, driven by the need to predict the annual flooding of the Nile, developed a solar calendar based on the heliacal rising of Sirius (Sopdet). The reappearance of Sirius in the morning sky just before sunrise, after a period of invisibility, signaled the imminent inundation of the Nile, a crucial event for their agricultural society. Their calendar, initially lunar-based, transitioned to a 365-day solar calendar, demonstrating their accurate tracking of solar cycles. Egyptian temples, such as Denderah, feature intricate astronomical ceilings depicting constellations and planetary movements, indicating a rich celestial iconography alongside practical calendrical applications.

These cultures viewed the heavens not as distant, unfeeling spheres, but as vital, interactive elements that governed earthly existence. The stars were both a clock and a compass, dictating agricultural cycles and guiding spiritual beliefs.

Ancient China: Precision and Persistence

Ancient China boasts an unbroken tradition of astronomical observation spanning millennia, characterized by rigorous record-keeping and sophisticated instrumentation. Their astronomers meticulously documented celestial events, contributing significantly to humanity’s understanding of the cosmos.

- Star charts and celestial atlases: Chinese astronomers compiled some of the earliest and most comprehensive star charts. The Dunhuang Star Chart, dating to the Tang Dynasty (circa 700-750 CE), depicts over 1,300 stars alongside constellations and the celestial equator. This meticulously drawn chart demonstrates advanced observational techniques and a systematic approach to cataloging the heavens. These charts were not merely theoretical constructs; they were practical tools for navigation, timekeeping, and astrological predictions.

- Recording of supernovae and comets: Chinese astronomical records are legendary for their unparalleled detail and continuity. They contain some of the earliest and most accurate accounts of supernovae, such as the guest star of 1054 CE, which is now understood to be the Crab Nebula. Their records of comets, meteors, and eclipses provided crucial data points for understanding celestial mechanics and served as vital historical references for astronomical research even today. This persistent recording across dynasties provided a long-term cosmic weather report, allowing for the identification of patterns and anomalies that might have escaped cultures with less continuous documentation.

- Calendrical systems and gnomons: Chinese calendrical systems were highly sophisticated, incorporating both solar and lunar cycles. They utilized instruments like gnomons (a simple stick casting a shadow) to precisely measure the sun’s position and track the seasons. The accuracy of their calendars was paramount for agricultural planning and imperial administration, underscoring the practical application of their astronomical expertise.

The Chinese astronomical tradition exemplifies a long-term commitment to empirical observation and systematic documentation, forming a bedrock of global astronomical knowledge. Their star maps were not just visual representations, but also statistical databases, invaluable for both immediate practical needs and long-term scientific inquiry.

The Hellenistic and Roman Worlds: Geocentric Models and Planetary Theories

The intellectual ferment of the Hellenistic and Roman periods led to significant advances in theoretical astronomy, culminating in comprehensive geocentric models that dominated Western thought for over a millennium.

Greek Astronomy: From Anaximander to Ptolemy

Greek philosophers and mathematicians fundamentally shaped astronomical thought, moving from mythological explanations to more structured, mathematical models of the universe.

- Early cosmological models: Early Greek thinkers, such as Anaximander, proposed cosmologies that sought to explain the arrangement and movement of celestial bodies. While often speculative, these initial attempts to rationalize the cosmos laid the groundwork for more scientific approaches. The concept of an Earth-centered universe, held aloft in a void or supported by water, gave way to more sophisticated models of nested spheres.

- **Ptolemy’s Almagest and geocentric dominance:** Claudius Ptolemy, in the 2nd century CE, consolidated and expanded upon centuries of Greek astronomical observations and theories in his monumental work, the Almagest. This treatise presented a comprehensive geocentric model of the universe, with the Earth at its center and the Sun, Moon, and planets orbiting it on complex epicycles and deferents. The Almagest was not merely a descriptive work; it provided a mathematical framework that could accurately predict planetary positions, making it the authoritative text on astronomy for over 1400 years. His work was both a culmination and a ceiling for astronomical thought in the West for a significant period.

- Eratosthenes’ measurement of Earth’s circumference: Eratosthenes, in the 3rd century BCE, famously calculated the circumference of the Earth with remarkable accuracy using simple geometry and observations of shadows cast by the sun at different locations. This intellectual feat demonstrated the power of scientific inquiry and the ability to deduce large-scale cosmic properties from local observations, pushing beyond mere description to quantitative analysis.

The Greeks, through their emphasis on geometry and logical deduction, transformed astronomy into a more rigorous scientific discipline, albeit within the confines of a geocentric worldview. Their models, while ultimately superseded, represented a pinnacle of ancient scientific achievement.

Roman Calendar Reform: Julian to Gregorian

While not known for groundbreaking theoretical astronomy, the Romans excelled in the practical application of calendrical systems, particularly for administrative and religious purposes.

- The Julian Calendar: The Roman Republic’s ancient lunar calendar was notoriously unwieldy and often fell out of sync with the seasons. Julius Caesar, in collaboration with the astronomer Sosigenes of Alexandria, initiated a major calendar reform in 45 BCE, resulting in the Julian Calendar. This solar calendar featured a year of 365 days, with an extra leap day every four years, closely approximating the tropical year. The Julian Calendar was a monumental achievement in practical timekeeping, providing a stable and accurate system that endured across Europe for over 1600 years. Its adoption standardized timekeeping across a vast empire, facilitating administration and accurate record-keeping.

- Need for the Gregorian reform: Despite its widespread adoption, the Julian Calendar contained a slight error: it overestimated the length of the tropical year by approximately 11 minutes. Over centuries, this accumulated error caused the date of the vernal equinox to drift, impacting the accurate calculation of Easter. This slow divergence, a cosmic clock that had begun to trickle out of sync, necessitated further reform.

- The Gregorian Calendar’s precision: By the 16th century, the Julian Calendar’s inaccuracy became a significant concern for the Catholic Church. Pope Gregory XIII, in 1582, introduced the Gregorian Calendar, which refined the leap year rule, omitting three leap years every 400 years. This adjustment brought the calendar into much closer alignment with the tropical year, achieving a precision still largely in use today. The adoption of the Gregorian Calendar, though initially met with resistance, ultimately provided humanity with a highly accurate and globally recognized system for tracking time, a testament to the ongoing refinement of our cosmic chronometers.

These developments highlight a crucial theme: the continuous process of observation, calculation, and refinement that defines the scientific pursuit of knowledge, a journey from rudimentary mapping to increasingly precise measurement.

Indigenous Celestial Knowledge: A Rich and Diverse Tapestry

Beyond the Eurasian and North African narratives, indigenous cultures around the world developed intricate and deeply spiritual connections with the cosmos, weaving astronomical knowledge into their social structures, rituals, and mythology.

North American Indigenous Astronomy: Oral Traditions and Sacred Sites

Indigenous peoples of North America possessed sophisticated astronomical knowledge, often passed down through generations via rich oral traditions and encoded within their sacred sites.

- Chaco Canyon and celestial alignments: The Ancestral Puebloan people of Chaco Canyon in New Mexico designed structures such as Fajada Butte and Casa Rinconada with precise astronomical alignments. The “Sun Dagger” on Fajada Butte, where three slabs of rock channel sunlight to create a dagger-like image that bisects a spiral petroglyph at the summer solstice, demonstrates advanced understanding of solar cycles. These sites served not only as observatories but also as ceremonial spaces, melding scientific observation with spiritual practice. They acted as living calendars, marking the passage of seasons and the rhythm of life.

- Pawnee star lore: The Pawnee people of the Great Plains had an extensive cosmology centered around the stars. Their ceremonies and agricultural practices were deeply intertwined with celestial observations, particularly the rising and setting of specific stars and constellations. They viewed the stars as ancestors and deities, their positions guiding everything from planting times to spiritual journeys. Their star charts were not just visual aids but integral parts of their worldview.

- Medicine wheels as astronomical observatories: Medicine wheels, stone structures found across the Great Plains, are often interpreted as astronomical observatories. The Bighorn Medicine Wheel in Wyoming, for instance, has spokes radiating from a central cairn, aligning with solstices and the rising points of significant stars like Aldebaran and Sirius. These structures represent a communal effort to track celestial movements and mark important seasonal and ceremonial dates.

These examples illustrate the profound integration of astronomy into the daily lives and spiritual beliefs of North American indigenous cultures, where the sky was not just a backdrop but an active participant in their existence. Their knowledge systems represent a unique convergence of scientific observation and profound cultural meaning.

Mesoamerican Calendars: The Maya and Aztec Complexities

Mesoamerican civilizations, particularly the Maya and Aztec, developed extraordinarily complex and accurate calendrical systems, demonstrating unparalleled sophistication in long-term timekeeping and astronomical prediction.

- Maya Long Count and Tzolkin/Haab’ cycles: The Maya civilization developed multiple interconnected calendars. The Tzolkin, a 260-day sacred calendar, and the Haab’, a 365-day civil calendar, intermeshed to form a 52-year “Calendar Round.” Beyond this, the Maya employed the Long Count calendar, a vast chronological system that counts days from a mythical starting point, allowing for the tracking of immense spans of time. This system enabled them to record and predict astronomical phenomena over millennia, revealing an obsession with the precise measurement of time, akin to a cosmic odometer.

- Venus cycle and its significance: The Maya were meticulous observers of Venus, tracking its 584-day cycle with remarkable precision. Their Dresden Codex contains detailed ephemerides for Venus, including calculations for its rising and setting phases. The motion of Venus held profound astrological and mythological significance for the Maya, influencing warfare, agricultural cycles, and religious ceremonies. Their predictions were so accurate that they rivalled, and in some cases surpassed, those of contemporary European astronomers.

- Aztec calendar stone: The iconic Aztec Calendar Stone, or “Sun Stone,” while often referred to as a calendar, functions more as a cosmic map and mythological compendium. It depicts the Aztec cosmos, including their creation myths, previous world eras, and astronomical cycles. It represents a synthesis of their calendrical knowledge, cosmology, and religious beliefs, providing a tangible representation of their understanding of time and the universe.

The Mesoamerican calendars stand as towering achievements in ancient astronomy, demonstrating an intellectual rigor and a dedication to understanding the cosmos that few other cultures matched. Their systems were not merely tools for tracking time but blueprints for comprehending the very fabric of existence.

Polynesian Navigation: Wayfinding by the Stars

The Polynesian navigators, often hailed as the greatest seafarers in history, mastered the art of long-distance canoe voyaging across vast stretches of the Pacific Ocean using an intricate knowledge of stars, currents, and swell patterns.

- Star compass and stellar pathways: Polynesian navigators employed a sophisticated “star compass,” a mental map of the horizon divided into points where specific stars and constellations would rise and set. They memorized hundreds of these stellar pathways, enabling them to pinpoint their location and maintain their course across thousands of miles of open ocean. The sky was their primary navigational instrument, its predictable rhythms their guide.

- Celestial memory systems: This vast body of astronomical knowledge was not recorded in written texts but maintained through elaborate oral traditions, chants, and mnemonic devices. Young navigators spent years learning the movements of celestial bodies, the direction of ocean swells, and the location of islands relative to those cosmic markers. This living database of celestial information was meticulously passed down from generation to generation, ensuring the perpetuation of their extraordinary navigational skills.

- Return voyages and precise landfalls: The ability of Polynesian navigators to make precise landfalls on small, distant islands, often after voyages lasting months, stands as a testament to their exceptional astronomical expertise. They effectively used the entire night sky as a grand, ever-present map, knowing that each star held a specific address on the horizon.

The Polynesian tradition exemplifies how highly practical astronomical knowledge can be developed and maintained without formal written systems, proving that the human mind can serve as a powerful and sophisticated celestial database. Their celestial knowledge was not just academic; it was existential, enabling the very survival and expansion of their culture.

Ancient star maps and celestial calendars have long fascinated historians and astronomers alike, revealing the intricate ways in which early civilizations understood and interacted with the cosmos. For a deeper exploration of this topic, you might find the article on celestial navigation particularly enlightening. It discusses how ancient cultures used the stars for navigation and timekeeping, showcasing their remarkable knowledge of astronomy. To read more about this fascinating subject, check out the article here.

Legacy and Modern Interpretations

| Culture | Time Period | Type of Star Map | Purpose | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Babylonian | c. 1800 BCE – 500 BCE | Clay tablets with star catalogues | Astronomical observations, calendar regulation | Detailed constellations, zodiac signs |

| Ancient Egypt | c. 3000 BCE – 1000 BCE | Ceiling star maps in tombs | Religious and funerary purposes, timekeeping | Decans system, alignment with Nile flooding |

| Chinese | c. 1000 BCE – 1600 CE | Star charts on silk and paper | Astronomy, astrology, calendar creation | 28 lunar mansions, precise star positions |

| Mayan | c. 300 BCE – 900 CE | Codices with celestial calendars | Religious ceremonies, agricultural cycles | 260-day Tzolk’in calendar, Venus cycles |

| Greek | c. 500 BCE – 200 CE | Star catalogues and celestial globes | Navigation, mythology, timekeeping | Constellation system, Ptolemy’s Almagest |

The ancient star maps and celestial calendars we have discussed are not mere relics of the past. They represent foundational scientific and cultural achievements that continue to inform and inspire us today.

Enduring Influence on Modern Astronomy and Culture

The astronomical observations and calendrical innovations of ancient civilizations form the bedrock upon which modern astronomy was built. Concepts such as the zodiac, the division of the year, and an understanding of planetary movements, however refined, all trace their lineage back to these pioneers.

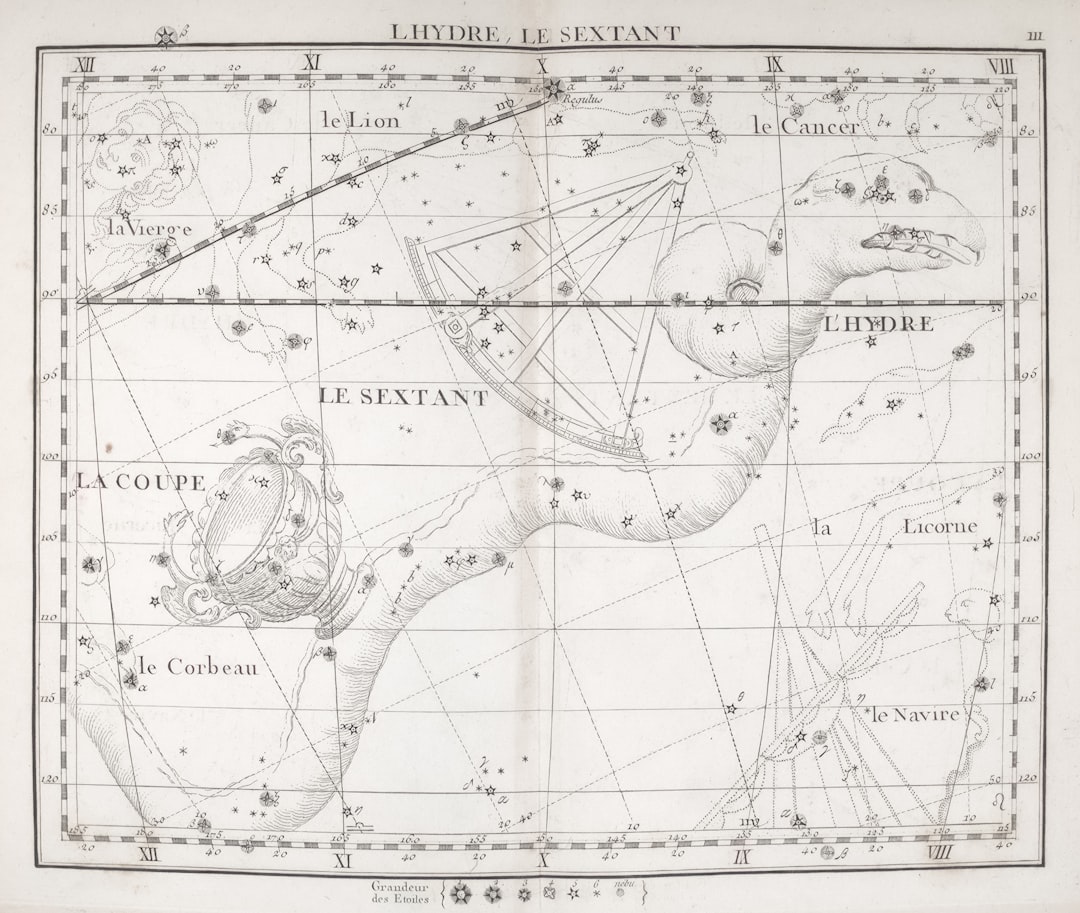

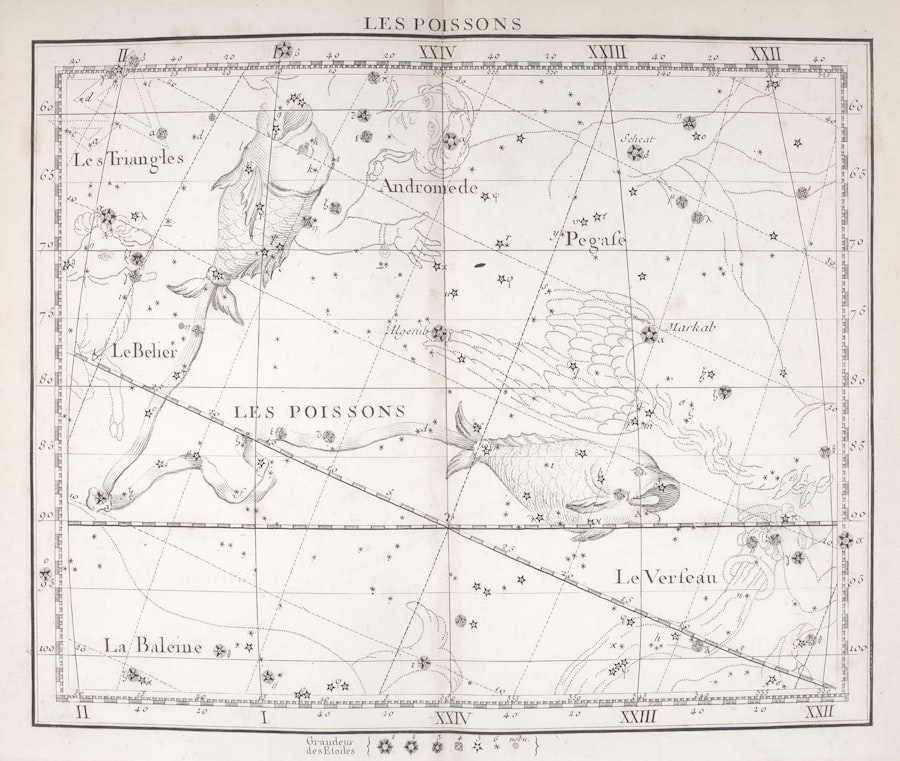

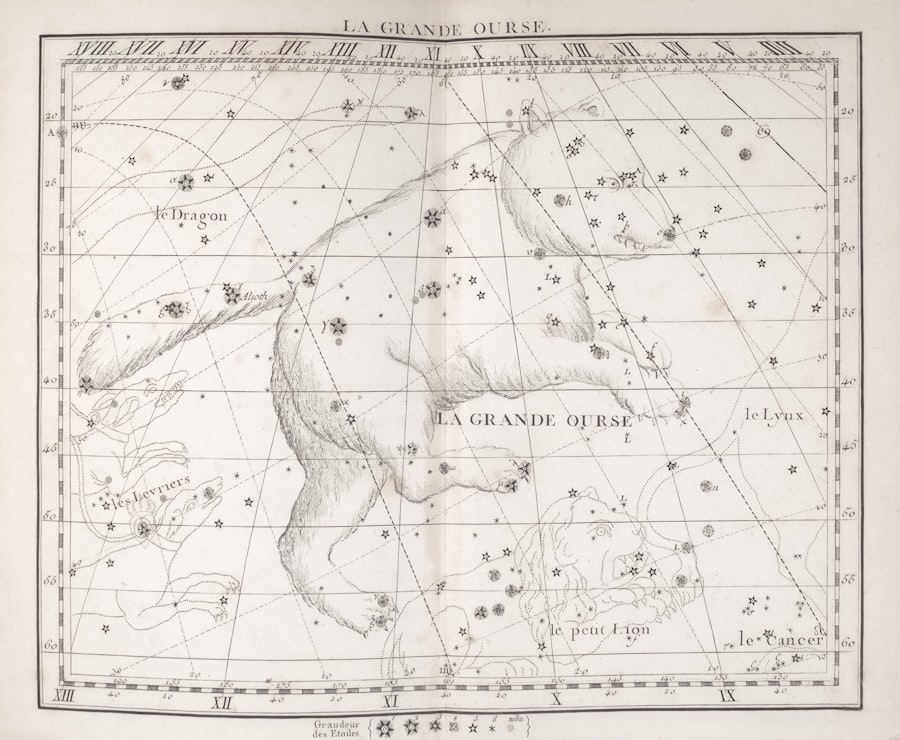

- Foundations of astronomical charting: Modern star charts, while vastly more detailed and precise due to telescopic observations and computational power, fundamentally build upon the ancient practice of mapping celestial objects and grouping them into constellations. The very names of many stars and constellations we use today carry echoes of ancient mythologies and observations. Ancient maps provided the initial coordinates, a cosmic grid laid out by prior generations.

- Calendrical systems worldwide: The Gregorian Calendar, dominant globally, is a direct descendant of the Roman Julian Calendar, which itself drew upon Egyptian solar reckoning. The principles of tracking solar and lunar cycles, of incorporating leap days, and of aligning human activity with seasonal change, are ancient intellectual inheritances. Our modern sense of time is implicitly linked to these ancient rhythms.

- Cultural and mythological connections: The stars continue to capture our imagination, inspiring literature, art, and film. Many constellations derive from Greek and Mesopotamian myths, weaving ancient narratives into the fabric of our contemporary understanding of the night sky. The celestial sphere still operates as a vast canvas for our stories, connecting us to deep human intellectual and spiritual heritage.

These ancient endeavors remind us that the human quest for understanding the cosmos is a continuous journey, a persistent effort to read the grand celestial clock and compass that governs our existence. The wisdom encoded in these ancient maps and calendars, whether carved into stone or held in memory, provides a profound connection to the intellectual spirit of our ancestors and underscores the enduring power of human curiosity. To look up at the night sky is, in a very real sense, to engage in a conversation across millennia with those who first began to chart its mysteries.

STOP: Why They Erased 50 Impossible Inventions From Your Textbooks

FAQs

What are ancient star maps?

Ancient star maps are historical representations of the night sky created by early civilizations. They depict the positions of stars, constellations, and other celestial objects as observed from Earth, often used for navigation, timekeeping, and religious purposes.

How were celestial calendars used in ancient times?

Celestial calendars were used to track time based on the movements of the sun, moon, stars, and planets. Ancient cultures used these calendars to determine agricultural cycles, religious festivals, and important societal events by observing celestial patterns.

Which civilizations are known for creating ancient star maps?

Several ancient civilizations created star maps, including the Babylonians, Egyptians, Greeks, Chinese, and Mayans. Each culture developed unique methods and symbols to represent the night sky according to their astronomical knowledge and cultural beliefs.

What materials were used to create ancient star maps?

Ancient star maps were made using various materials such as stone, clay tablets, papyrus, parchment, and wood. Some were carved, painted, or inscribed with symbols and drawings to illustrate celestial bodies and constellations.

How accurate were ancient star maps and celestial calendars?

While not as precise as modern astronomical tools, many ancient star maps and celestial calendars were remarkably accurate for their time. They allowed early astronomers to predict celestial events like solstices, eclipses, and planetary movements with considerable reliability.