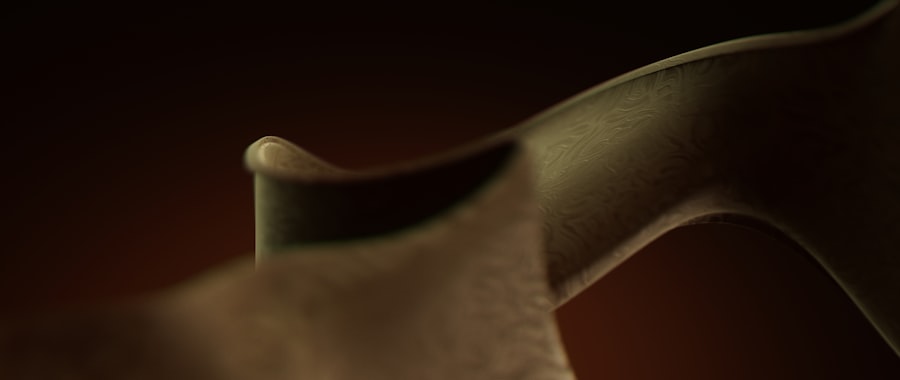

The legendary bloom of Damascus steel, with its mesmerizing swirling patterns, has captivated swordsmiths and warriors for centuries. Yet, the secrets of its creation, and more specifically, the reasons behind the loss of these distinctive patterns, remain a subject of intense study and debate. This article delves into the enigmatic phenomenon of Damascus steel pattern loss, exploring the scientific and historical factors that contribute to this fascinating metallurgical puzzle.

Before one can comprehend the loss of Damascus steel’s signature aesthetic, a foundational understanding of its creation is paramount. The original, true Damascus steel, also known as Wootz steel, was a crucible steel produced in India and the Middle East from around 300 BCE to the 18th century CE. Its hallmark was its exceptional strength, sharpness, and the indelible visual patterns that graced its surface. These patterns were not mere decoration; they were intrinsic to the steel’s microstructure and, by extension, its superior performance.

The Crucible Process: A Black Box of Innovation

The production of Wootz steel was a closely guarded secret, passed down through generations of smiths. While the precise recipe and techniques were lost to time, archaeological and scientific investigations have shed considerable light on the process. It involved smelting iron ore with carbon-rich plant materials in a sealed crucible, a ceramic container, for extended periods at high temperatures. This controlled heating and cooling process was the crucible, quite literally, for the formation of the unique microstructures.

Microstructural Marvels: The Role of Carbides

The distinctive patterns of true Damascus steel are attributed to the presence of specific carbide structures within the steel matrix. These carbides, primarily iron carbides (cementite), precipitate out of the molten steel during the cooling process. The rate and manner of cooling, along with the specific chemical composition of the bloom, dictated the size, distribution, and morphology of these carbide particles.

Banded Microstructures: The Foundation of the Pattern

The characteristic “watered” or “webbed” appearance of Damascus steel arises from the segregation of carbon and alloying elements. During the slow cooling of the crucible, higher carbon content regions would lead to the formation of a greater density of carbides. This segregation, coupled with the anisotropic properties of the ferrite and pearlite phases, resulted in banded microstructures that, when etched, revealed the intricate patterns. Think of it as layers of varying density, where light and shadow play to highlight the underlying structure.

Inclusions and Impurities: Unintended Architects of Ornamentation

While modern metallurgy strives for purity, the Wootz steel of antiquity often contained impurities. Certain non-metallic inclusions, such as slag and oxides, were also found within the steel. Surprisingly, some of these impurities may have played a role in further accentuating the visible patterns. Their presence could disrupt the uniform precipitation of carbides, leading to localized variations that enhanced the visual complexity. It’s akin to a painter adding subtle textures to a canvas to create depth.

The Metallurgy of Performance: Beyond Aesthetics

It is crucial to reiterate that the patterns on true Damascus steel were never merely for show. The microstructural features responsible for the visual patterns were also directly linked to the steel’s exceptional metallurgical properties. The high carbon content and the presence of uniformly distributed carbides contributed to its remarkable hardness and edge retention, while the surrounding ferrite matrix provided toughness. This dual nature made these blades formidable weapons.

The mystery surrounding the loss of the distinctive patterns in Damascus steel has intrigued metallurgists and historians alike for centuries. Recent studies have shed light on the techniques used by ancient craftsmen, revealing that the unique patterns were not merely aesthetic but also indicative of the steel’s composition and properties. For those interested in delving deeper into this fascinating topic, a related article can be found at this link, which explores the historical significance and modern implications of Damascus steel’s pattern loss.

The Forging and Manipulation of Damascus Steel

The creation of a finished Damascus steel blade involved more than just the initial crucible process. The subsequent hot working, or forging, of the bloom was just as critical in shaping both the form and the visible patterns of the steel. This stage offered smiths a degree of control over the final appearance, allowing them to coax out and refine the inherent patterns.

Heat Treatment: The Sculptor’s Touch

The thermal cycling applied during forging and subsequent heat treatments were crucial in manipulating the carbide distribution and crystallographic orientation, which in turn influenced the visibility and coarseness of the damask pattern. The smith’s skill in controlling temperatures and the number of forging cycles was a masterful dance with the metal. Each hammer blow, each dip into the quenching medium, was a deliberate stroke shaping the destiny of the steel.

Quenching and Tempering: The Art of Precision

The specific quenching and tempering processes employed by ancient smiths are still subjects of investigation. Different cooling rates and tempering temperatures would have resulted in varying amounts of martensite, pearlite, and bainite in the microstructure, each contributing to the overall characteristics and pattern visibility of the Damascus steel. This was a precise chemical and physical ballet, where time and temperature were the conductors.

Differential Etching: Revealing the Hidden Depths

Once forged and heat-treated, the surface of a Damascus steel blade would be subjected to differential etching. This process uses acids to selectively attack different microstructural components of the steel. The harder, more carbide-rich areas would resist the acid longer, appearing lighter, while the softer, ferrite-rich areas would be etched more deeply, appearing darker. It was through this selective corrosion that the intricate patterns were finally brought to light, like a revelation from the depths of the material.

The Role of the Etchant: A Revealing Agent

The choice of etchant and the duration of the etching process were critical in achieving the desired pattern definition. Different acids would interact with the microstructures in varying ways, revealing nuances and details that might otherwise remain hidden. The etchant acted as a wise storyteller, drawing out the narrative of the steel’s creation.

Factors Contributing to Damascus Steel Pattern Loss

The loss of the distinctive patterns in Damascus steel, while seemingly a metallurgical tragedy, is a phenomenon that can occur due to a confluence of factors. These can range from the inherent nature of the steel itself to the stresses and environments it has endured over time. Understanding these causes is key to appreciating why some blades retain their luster while others fade into obscurity.

Thermal Degradation: The Slow Burn of Time

One of the most significant contributors to Damascus steel pattern loss is thermal degradation. Prolonged exposure to elevated temperatures, even below the steel’s melting point, can cause the carbide structures to coarsen and spheroidize. This process, known as annealing, essentially breaks down the fine, elongated carbide structures into rounded particles.

Carbide Coarsening: Blurring the Edges

As carbide particles coarsen, they become less distinct and their banding becomes less pronounced. The sharp contrast that once defined the pattern begins to blur, leading to a more uniform appearance. Imagine the sharp lines of a drawing slowly softening and becoming smudged.

Spheroidization: A Homogenizing Effect

Spheroidization is a further stage of carbide coarsening where the carbides transform into near-spherical shapes. This greatly reduces their visibility within the ferrite matrix, and if this process becomes widespread, the characteristic pattern can be effectively erased. The formerly distinct architectural elements are reduced to a homogenous, less visually interesting paste.

Mechanical Stress and Deformation: Hammering Away the Memories

While forging is essential to reveal the patterns, excessive or improper mechanical stress can also lead to their degradation. Severe plastic deformation, such as can occur through repeated impacts or aggressive grinding, can disrupt the carbide distribution and alter the crystallographic orientation of the grains.

Recrystallization and Grain Growth: Reshaping the Landscape

Under significant mechanical stress and elevated temperatures (such as during prolonged grinding), recrystallization can occur. This process involves the formation of new, strain-free grains. Subsequent grain growth can then lead to a larger, more uniform grain structure, which can obscure the original banding and carbide patterns. The intricate tapestry of the old is replaced by a coarser, more uniform weave.

Surface Grinding and Polishing: The Double-Edged Sword

Aggressive surface grinding and polishing, while intended to refine the surface finish, can inadvertently remove or distort the delicate microstructural features responsible for the damask pattern. If the grinding depth is too great, it can reach below the original patterned layer, revealing a flatter, less decorated microstructure. This is a delicate act of balance; too much pressure can erase the masterpiece.

Chemical Attack and Corrosion: The Slow Erosion of Detail

The surface of any metal is susceptible to chemical attack and corrosion. For Damascus steel, this can lead to the selective removal of material, altering the pattern or even causing pitting. Overt exposure to corrosive environments or aggressive cleaning agents can have a detrimental effect.

Rusting and Oxidation: The Unwanted Patina

The formation of rust and other oxides on the surface can obscure the underlying patterns. While some patina can add character, excessive or uneven corrosion can definitely degrade the visual appeal. Think of a grand old building whose intricate carvings are slowly being eroded by the elements.

Etching Mishaps: Overzealous Revelations

As mentioned earlier, etching is crucial for revealing the patterns. However, improper or overly aggressive etching can lead to excessive material removal, the rounding of carbide structures, and the obliteration of fine details. An overzealous historian might accidentally erase crucial details in their attempt to bring the past to light.

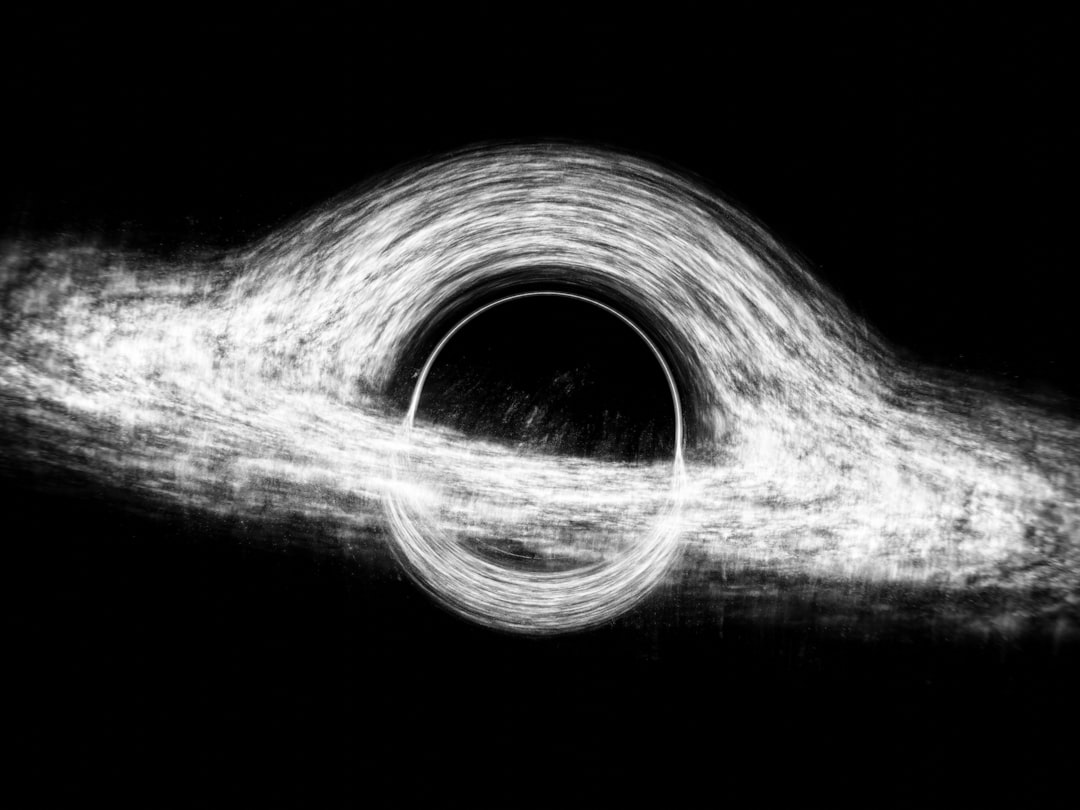

The Modern Quest for Authentic Damascus Steel and its Patterns

The mystery surrounding the original Damascus steel and its unparalleled performance has spurred a modern revival of its production. However, the term “Damascus steel” today often refers to a different metallurgical process than the historical Wootz steel. This has led to a distinction between “true” Damascus steel and modern “pattern-welded” steel.

Pattern-Welded Steel: A Modern Interpretation

Modern pattern-welded steel is created by forge-welding together layers of different steels with varying compositions and carbon content. These layers are then manipulated through folding, twisting, and other decorative techniques before being etched to reveal the created patterns. While often aesthetically pleasing, the microstructural origins of these patterns differ from those of ancient Wootz steel.

Differences in Carbide Formation: The Fundamental Divide

In pattern-welded steel, the patterns are largely a result of the visible boundaries between the different welded layers, which have been differentially etched. The carbide structures within these layers are generally not as inherently banded or as precisely controlled as in true Damascus steel. This means that while visually striking, the performance characteristics may not fully replicate the historical marvel.

The Challenge of Mimicking Wootz: An Unfinished Symphony

Replicating the precise crucible process and the resulting unique carbide structures of true Damascus steel remains an ongoing challenge for metallurgists. The exact combination of raw materials, furnace atmosphere, and thermal cycles required to produce the signature Wootz microstructure is still not fully understood or consistently reproducible. It is like trying to recreate a lost masterpiece without the original blueprints.

Identifying True Damascus Steel: A Detective’s Pursuit

Distinguishing between true historical Damascus steel and modern pattern-welded steel relies on a combination of visual inspection, metallurgical analysis, and sometimes, historical provenance. Microstructural examination is often the most definitive method.

Microstructural Analysis: The Microscopic Microscope

Techniques such as optical microscopy, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) can reveal the characteristic banded carbides of real Damascus steel and differentiate them from the layered structures of pattern-welded steel. This is where the detective dons their magnifying glass to uncover the truth.

Hardness and Performance Testing: The Ultimate Verdict

The metallurgical properties, such as hardness, toughness, and edge retention, can also provide clues. True Damascus steel was renowned for its exceptional balance of these attributes. While modern pattern-welded steels can be excellent blades, they may not always achieve the same unique combination of properties as their ancient counterparts.

The mystery surrounding the loss of the distinctive patterns in Damascus steel has intrigued historians and metallurgists alike, leading to various theories about its production techniques. A fascinating article that delves deeper into this topic can be found at Real Lore and Order, where it explores the historical significance and the modern implications of this ancient craftsmanship. Understanding the reasons behind the fading patterns not only sheds light on the artistry of the past but also informs current practices in metalworking.

Preservation and Restoration of Damascus Steel Patterns

| Aspect | Description | Known Data / Metrics | Current Theories |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pattern Formation | Distinct wavy or watery patterns on Damascus steel blades | Patterns result from layering and folding of steel alloys | Microstructure of carbon and iron layers creates pattern |

| Original Damascus Steel | Steel produced in the Near East from 300 BC to 1700 AD | Wootz steel ingots imported from India and Sri Lanka | Unique impurities and forging techniques caused pattern |

| Pattern Loss Mystery | Inability to reproduce original Damascus steel patterns today | No exact modern replication of original microstructure | Loss of original ore sources and forging knowledge |

| Material Composition | Carbon content and trace elements in steel | Original Wootz steel had 1-2% carbon, with vanadium traces | Vanadium may have contributed to pattern formation |

| Forging Techniques | Folding, hammering, and heat treatment methods | Ancient methods involved repeated folding and controlled cooling | Exact temperature control and timing critical but lost |

| Modern Attempts | Recreation of Damascus steel using modern metallurgy | Pattern-welded steels mimic appearance but differ microstructurally | Modern steels lack original impurities and forging nuances |

| Scientific Studies | Analysis of ancient blades using microscopy and spectroscopy | Revealed carbide networks and microsegregation patterns | Supports theory of unique carbon diffusion and alloying |

For collectors and enthusiasts of historical Damascus steel, the preservation and, in some cases, restoration of its distinctive patterns are of paramount importance. Understanding how to protect these artifacts from further degradation is as vital as understanding the causes of their loss.

Environmental Controls: Creating a Sanctuary

Proper storage and display are crucial for preventing environmental damage. Damascus steel artifacts should be kept in stable environments with controlled humidity and temperature, away from direct sunlight and corrosive agents. Creating a protected microclimate can be the shield that guards against the ravages of time.

Humidity and Temperature: The Unseen Enemies

Fluctuations in humidity and temperature can accelerate corrosion and thermal degradation. Maintaining a consistent environment minimizes these risks. Like a delicate manuscript needing protection from dampness, Damascus steel requires a carefully managed habitat.

Exposure to Light and Chemicals: Avoiding Damaging Influences

Bright lights can contribute to material degradation over long periods, and exposure to chemicals, even cleaning agents, can be detrimental. It is best to handle these artifacts with clean hands and to avoid any abrasive or chemically aggressive cleaning methods.

Gentle Cleaning and Maintenance: A Light Touch

When cleaning is necessary, it should be done with the utmost care. Soft brushes and mild, non-abrasive cleaning agents are recommended. The goal is to remove surface contaminants without damaging the underlying microstructure. A gentle pat on the back is more effective than a harsh reprimand.

Non-Abrasive Materials: Tools of Preservation

Using lint-free cloths, soft bristle brushes, and specialized conservation waxes can help maintain the surface without causing abrasion. The right tools are key to a sympathetic touch.

Avoiding Harsh Chemicals: The Perils of Potency

Strong acids, abrasives, and industrial cleaners should be strictly avoided. These can easily etch or damage the delicate patination and microstructures. A strong dose of the wrong medicine can be more harmful than the ailment.

Professional Conservation: Expert Interventions

For valuable or significantly degraded Damascus steel artifacts, professional conservation by experienced conservators is often the best course of action. These experts possess the knowledge and techniques to assess damage and undertake delicate restoration work. Their keen eyes can often discern the original intent of the smith and guide the preservation efforts.

Metallurgical Assessment: Diagnosing the Distress

A conservator will first perform a thorough metallurgical assessment to understand the current state of the steel and the nature of any degradation. This diagnosis is the first step towards effective treatment. It’s like a doctor examining a patient before prescribing a cure.

Delicate Restoration Techniques: Surgical Precision

Restoration techniques may involve carefully controlled mechanical cleaning, microscopic adjustments to surface irregularities, or chemical treatments applied with extreme precision. The aim is always to stabilize the artifact and reveal its inherent beauty without compromising its integrity. This is not brute force; it is surgical precision, guided by deep understanding.

The mystery of Damascus steel pattern loss is a multifaceted puzzle, weaving together the ingenuity of ancient metallurgy, the subtle workings of material science, and the inexorable march of time. While the secrets of original Wootz production may never be fully unveiled, ongoing research and dedicated conservation efforts continue to illuminate our understanding of this legendary material, ensuring that its mesmerizing patterns, and the stories they tell, endure.

SHOCKING: 50 Artifacts That Prove History Was Erased

FAQs

What is Damascus steel?

Damascus steel refers to a type of steel known for its distinctive wavy or patterned surface, historically used in sword and knife making. It is renowned for its strength, durability, and unique aesthetic patterns.

Why is the pattern in Damascus steel considered a mystery?

The pattern in Damascus steel is considered a mystery because the original methods used to create the distinctive layered and wavy designs were lost over time. Modern metallurgists and blacksmiths have tried to replicate the patterns, but the exact ancient techniques remain uncertain.

How was Damascus steel originally made?

Historically, Damascus steel was made using a process involving the forging and folding of different types of steel and iron, often incorporating wootz steel ingots from India. This process created layers and patterns, but the precise details and materials used have not been fully documented.

What causes the unique patterns in Damascus steel?

The unique patterns in Damascus steel are caused by variations in carbon content and the layering of different steels during forging. The folding and hammering process creates contrasting bands of hard and soft metal, resulting in the characteristic wavy or watery appearance.

Is modern Damascus steel the same as historical Damascus steel?

Modern Damascus steel is often made using pattern welding techniques that mimic the appearance of historical Damascus steel. While visually similar, the chemical composition and manufacturing processes may differ from the original wootz steel methods, meaning modern Damascus steel is not always identical to the ancient material.