The annals of human history, as presented to the masses, often serve as a carefully curated narrative, a mosaic built with select tiles while countless others lie shattered beneath the surface. This article delves into the concept of “Suppressed Facts: History’s Lies,” exploring how historical accounts can be manipulated, selectively presented, or outright fabricated to serve various agendas. It encourages a critical examination of widely accepted truths and invites the reader to consider the implications of an incomplete or distorted past.

History, in its purest form, endeavors to reconstruct past events based on available evidence. However, this reconstruction is rarely a neutral process. The very act of selecting what to record, what to highlight, and what to disregard introduces inherent biases.

The Power of the Pen: Who Writes History?

The adage “History is written by the victors” encapsulates a fundamental truth. Those in power, whether conquerors, ruling elites, or dominant ideological factions, frequently shape the historical narrative to legitimize their authority, glorify their actions, and demonize their adversaries. This power extends to the control of archives, educational institutions, and media, effectively monopolizing the dissemination of historical knowledge. Consider, for instance, the historical accounts of colonial expansion. Often, these narratives focus on the “civilizing mission” and technological advancements of the colonizers, while minimizing or entirely omitting the brutality, exploitation, and cultural destruction inflicted upon indigenous populations.

The Echo Chamber of Belief: Ideological Filters

Ideology acts as a powerful filter through which historical events are interpreted. Political, religious, and economic ideologies often necessitate a specific historical trajectory to validate their contemporary claims. For example, nationalist histories frequently emphasize a nation’s heroic origins and inevitable destiny, downplaying internal divisions or less flattering episodes. Similarly, certain religious histories may focus on miracles and divine intervention, sometimes at the expense of secular explanations or alternative interpretations of events. This ideological framing can transform complex realities into simplified morality plays, where certain groups are perpetually virtuous and others inherently villainous.

The Selective Spotlight: What Gets Remembered?

Memory itself is a selective process, both individually and collectively. Societies tend to remember events that reinforce their identity, celebrate their triumphs, and mourn their losses in a way that aligns with their self-perception. Conversely, uncomfortable truths, embarrassing defeats, or instances of injustice perpetrated by one’s own group can be pushed into the shadows, either actively suppressed or simply allowed to fade from collective memory. The Armenian Genocide, for example, remains a contentious historical event, with some nations actively denying or downplaying its scale despite overwhelming evidence. This suppression highlights the political motivations behind historical remembrance and forgetting.

In exploring the theme that history is often a lie, suppressed facts play a crucial role in shaping our understanding of the past. A related article that delves into this topic is available at Real Lore and Order, where it discusses how narratives are constructed and the importance of questioning established historical accounts. This resource encourages readers to critically examine the information presented to them and to seek out the hidden truths that may have been overlooked or deliberately obscured.

The Architecture of Erasure: Destroying and Suppressing Evidence

Beyond mere selective interpretation, history can be actively twisted through the physical destruction of evidence or the systematic silencing of dissenting voices. This is not merely a matter of omission, but an active campaign to obliterate alternative narratives.

The Pyres of Knowledge: Book Burning and Archive Destruction

Throughout history, regimes and movements have resorted to destroying books, documents, and artifacts that contradict their preferred narratives. The burning of the Library of Alexandria, though its scale is debated, serves as a poignant metaphor for the loss of invaluable knowledge due to ideological fervor or political upheaval. More recently, the destruction of historical sites and cultural heritage by extremist groups demonstrates a conscious effort to erase the past and impose a singular, unchallengeable worldview. When physical evidence is eradicated, the task of historical reconstruction becomes exponentially more challenging, often leaving future generations reliant on incomplete or biased accounts.

The Silence of the Dissident: Suppressing Alternative Voices

Another insidious method of historical manipulation is the suppression of dissenting voices. Historians, scholars, or witnesses who present alternative interpretations or uncomfortable facts can face professional ostracization, censorship, imprisonment, or even execution. During totalitarian regimes, official histories are often the only ones permitted, with any deviation considered a threat to state power. Imagine, for a moment, a vast forest where only certain trees are allowed to bear fruit, while all others are systematically cut down. The resulting narrative, though appearing cohesive, is ultimately barren of true diversity and depth.

The Forgery and Fabrication: Inventing the Past

In some extreme cases, history is not merely distorted or suppressed, but outright fabricated. Forged documents, altered photographs, and manufactured testimonies can be used to create an entirely fictional past that serves contemporary political ends. The “Protocols of the Elders of Zion,” a notorious anti-Semitic forgery, successfully fueled prejudice and persecution for decades by fabricating a Jewish plot for world domination. These instances demonstrate the audacious lengths to which some will go to construct a past that underpins their agendas, transforming history from a pursuit of truth into a weapon of deception.

The Blind Spots of Progress: When “Enlightenment” Casts Shadows

Even in periods of perceived enlightenment and scientific advancement, historical narratives can be subject to profound biases that obscure uncomfortable truths or perpetuate deeply ingrained prejudices.

The Veil of Progress: Colonial Narratives and Western Centrism

For centuries, much of global history has been written through a distinctly Western-centric lens. Non-Western civilizations were often portrayed as primitive, static, or merely as backdrops for European expansion. This perspective frequently overlooked the rich intellectual traditions, sophisticated social structures, and significant scientific contributions of cultures outside of Europe. The “discovery” of new lands, for instance, glosses over the pre-existing vibrant civilizations that thrived there. This historical bias, often implicitly rather than explicitly stated, perpetuates a narrative of Western exceptionalism and can subtly devalue the experiences and achievements of the majority of humanity.

The Unseen Woman: Gendered Histories

Traditional historical accounts have predominantly focused on the actions and achievements of men, often relegating women to secondary roles or omitting their contributions entirely. The “great man” theory of history, which emphasizes the impact of influential male figures, has long dominated narratives of political, scientific, and artistic development. Consequently, the roles of women as leaders, innovators, caregivers, and cultural architects have often been minimized or overlooked, creating a historical record that is profoundly incomplete and gender-biased. The reader is encouraged to consider the wealth of stories and perspectives that remain untold due to this historical blind spot, like a vast continent yet to be fully charted.

The Voices from the Margins: Race and Class in Historiography

Similarly, the histories of marginalized groups, such as racial minorities, indigenous peoples, and the working class, have often been excluded or presented through the lens of dominant groups. Their struggles, resilience, and contributions have been systematically downplayed or ignored, leading to a distorted view of social dynamics and power structures. The history of slavery, for example, is often presented from the perspective of abolitionists or enslavers, with the lived experiences and agency of the enslaved given insufficient voice. Rectifying these historical omissions requires actively seeking out and amplifying the voices that have long been silenced, offering a more nuanced and just understanding of the past.

The Weaponization of the Past: Propaganda and Control

When history is manipulated, it cease to be a neutral record and transforms into a potent tool for propaganda, social control, and the perpetuation of existing power structures.

The Justification of Power: Historical Precedents

Rulers and political movements frequently invoke historical precedents to legitimize their actions and policies. By selectively citing past events or misrepresenting historical figures, they attempt to create an illusion of continuity and inevitability. A leader might claim a divine or ancient mandate for their rule, or a nation might justify territorial expansion by referencing historical claims that might be tenuous or selectively interpreted. This use of history as a “propaganda shield” deflects criticism and instills a sense of historical imperative in the populace. The past, in this context, becomes a malleable clay, sculpted to fit the present’s demands.

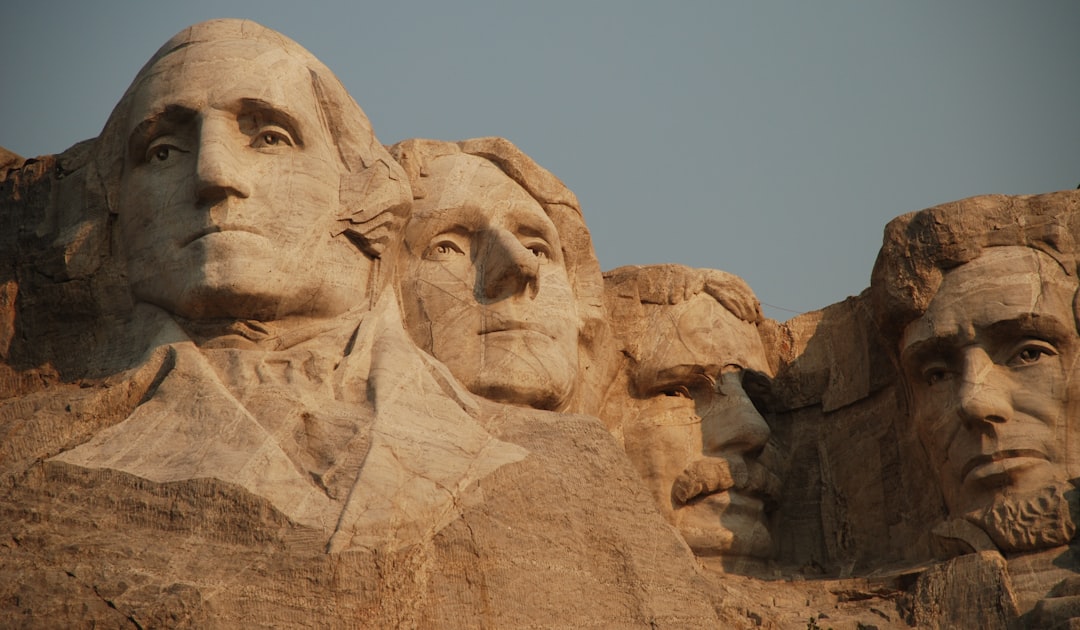

The Construction of Identity: National Myths and Collective Memory

National identity is often built upon a foundation of shared historical narratives, known as national myths. These myths, while often serving to foster unity and pride, can also simplify complex historical realities, demonize external “others,” and perpetuate a sense of victimhood or exceptionalism. The construction of a national hero, for example, might involve overlooking their flaws or controversial actions to present a pristine image that inspires patriotic fervor. While a sense of national identity can be a positive force, when built on selectively curated or fabricated historical accounts, it can lead to dangerous levels of chauvinism and an inability to critically assess a nation’s own past actions.

The Manipulation of Emotion: History as a Tool for Conflict

History, particularly when presented with strong emotional framing, can be a powerful catalyst for conflict. Narratives of past grievances, historical injustices, or perceived existential threats can be resurfaced and exploited to inflame passions, mobilize populations, and justify aggression. Consider the role of historical narratives in ethnic conflicts, where ancient feuds and injustices are rehashed and amplified to generate animosity and violence. The manipulation of historical memory in such cases transforms the past from a source of learning into a perpetual wound, constantly reopened for political advantage.

In exploring the theme that history is often a lie, suppressed facts can reveal a different narrative that challenges mainstream perspectives. A thought-provoking article that delves into this idea is available at this link, where various instances of overlooked historical events are discussed. By examining these suppressed truths, we can gain a deeper understanding of how history is shaped and the importance of questioning accepted narratives.

Towards a More Honest Past: Deconstructing and Reconstructing

| Aspect | Description | Example | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suppressed Facts | Information intentionally omitted or hidden from mainstream historical narratives. | The role of indigenous peoples in early American history often minimized. | Leads to incomplete or biased understanding of history. |

| Historical Revisionism | Re-examining and reinterpreting historical records, sometimes challenging accepted views. | Reevaluating causes of major wars or colonial impacts. | Can correct inaccuracies but sometimes used to distort facts. |

| Propaganda Influence | Use of biased or misleading information to promote a political cause or point of view. | State-controlled histories in authoritarian regimes. | Shapes public perception and national identity. |

| Oral Traditions | Historical accounts passed down verbally, often excluded from written history. | Indigenous stories explaining historical events. | Preserves alternative perspectives but may lack documentation. |

| Access to Archives | Availability of historical documents and records to researchers and the public. | Declassification of government files revealing new facts. | Enables more accurate and comprehensive history writing. |

The challenge of confronting “history’s lies” is not to dismiss all historical narratives, but to approach them with a healthy skepticism and a commitment to critical inquiry. The goal is not to erase the past, but to paint a more accurate and comprehensive picture.

The Historian’s Imperative: Critical Source Analysis

The foundation of historical deconstruction lies in rigorous source analysis. This involves questioning the origins, biases, and intentions of historical documents, eyewitness accounts, and archaeological findings. Who created this source? What was their agenda? What might they have omitted or emphasized? By interrogating sources, historians can move beyond surface narratives and uncover the complex layers of truth and interpretation. This is akin to a detective examining every piece of evidence, not merely accepting it at face value, but searching for clues about its provenance and reliability.

The Multiplicity of Perspectives: Seeking Diverse Voices

A critical approach to history necessitates actively seeking out and incorporating diverse perspectives. This means moving beyond dominant narratives and exploring the histories of marginalized groups, dissenting voices, and alternative interpretations. Ethnography, oral histories, and subaltern studies offer valuable tools for reconstructing narratives that have long been excluded from mainstream historical accounts. By embracing a multiplicity of perspectives, the panorama of the past widens, revealing details and nuances previously obscured.

The Ongoing Conversation: History as a Dynamic Process

History is not a static monolith, but rather an ongoing conversation, constantly re-evaluated and reconstructed as new evidence emerges and new interpretations gain traction. It is a continuous process of inquiry, debate, and revision. The reader should understand that historical “truth” is rarely absolute and often provisional, subject to change in light of new discoveries or evolving understandings. Embracing this dynamic nature of history allows for correction, reconciliation with uncomfortable truths, and ultimately, a more mature and responsible engagement with our collective past. The journey towards an honest past is an endless one, a perpetual excavation of meaning from the shifting sands of time.

FAQs

What does the phrase “history is a lie” mean?

The phrase “history is a lie” suggests that commonly accepted historical narratives may be incomplete, biased, or intentionally altered. It implies that some facts have been suppressed or omitted, leading to a distorted understanding of past events.

Why are some historical facts suppressed or overlooked?

Historical facts may be suppressed due to political agendas, cultural biases, or the desire to maintain certain power structures. Governments, institutions, or dominant groups might control historical narratives to influence public perception or national identity.

How can we identify suppressed facts in history?

Identifying suppressed facts involves critical examination of multiple sources, including primary documents, alternative perspectives, and marginalized voices. Cross-referencing accounts and consulting academic research can help uncover overlooked or hidden information.

Is all history unreliable or fabricated?

No, not all history is unreliable or fabricated. While some historical accounts may be biased or incomplete, many historians strive for accuracy and objectivity. History is a discipline that evolves as new evidence emerges and interpretations are reassessed.

What is the importance of acknowledging suppressed historical facts?

Acknowledging suppressed historical facts is important for a more accurate and inclusive understanding of the past. It helps address historical injustices, promotes critical thinking, and fosters a more informed and equitable society.