Here is an article exploring the religious suppression of ancient science, presented in a factual style, using third-person point of view, and adhering to your structural and stylistic requirements:

The annals of intellectual history are not a smooth, unbroken ascent toward enlightenment. Instead, they are a complex tapestry woven with threads of discovery, progress, and, at times, significant setbacks. One recurring theme that emerges from this intricate weave is the phenomenon of religious suppression of scientific inquiry in ancient civilizations. This suppression, often driven by a desire to maintain established doctrines, preserve social hierarchies, or control the flow of knowledge, acted as a potent dam, diverting the river of scientific understanding from its natural course and, in some instances, threatening to dry up its very springs.

Before examining instances of suppression, it is crucial to understand the fertile ground upon which ancient science once grew. Early civilizations, driven by practical needs and a deep curiosity about the cosmos and the natural world, laid the groundwork for scientific thought. These nascent disciplines were not always distinct from religious or philosophical pursuits, often existing in a fluid, intertwined state.

Early Observations and Practical Applications

The earliest forms of scientific endeavor were deeply rooted in the exigencies of daily life. Agriculture, architecture, navigation, and medicine all demanded a sophisticated understanding of natural phenomena.

Astronomy and Calendar Development

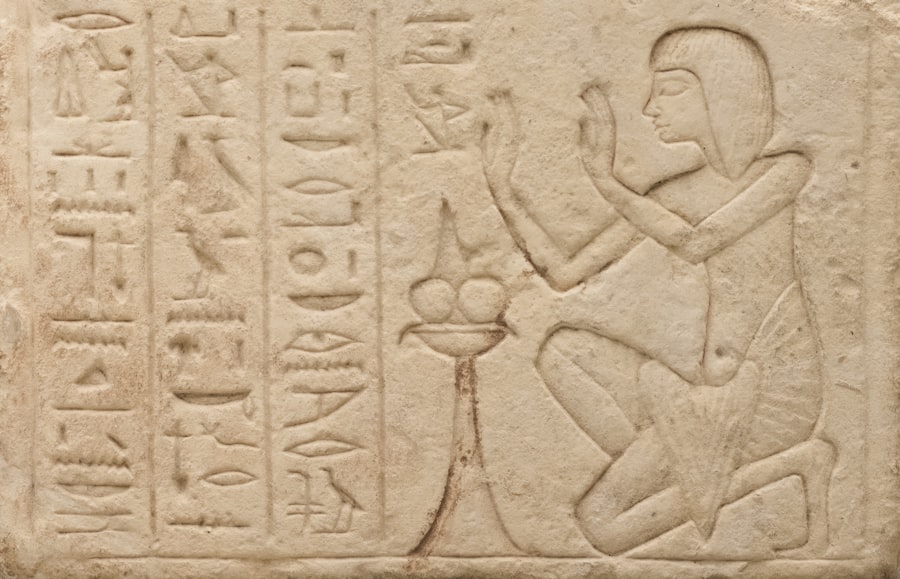

The predictable cycles of the sun, moon, and stars were not merely objects of wonder; they were vital for agriculture, guiding planting and harvesting seasons. Ancient Egyptians, for instance, meticulously observed the heliacal rising of Sirius, which coincided with the annual flooding of the Nile, a lifeblood for their civilization. Mesopotamian astronomers developed complex lunar calendars, essential for religious observances and civil administration. These early astronomical observations, while serving practical purposes, also fostered a nascent desire to understand the underlying order of the cosmos.

Mathematics and Engineering

The construction of monumental structures like the pyramids of Egypt and the ziggurats of Mesopotamia demanded advanced mathematical knowledge and engineering prowess. Understanding geometry was crucial for surveying land and designing stable edifices. Early forms of algebra and arithmetic were employed for accounting, resource management, and trade. The practical application of these disciplines demonstrated a capacity for abstract thought and problem-solving, hallmarks of scientific inquiry.

Medicine and Physiology

Ancient medical traditions, though often imbued with spiritual explanations for illness, also involved systematic observation and rudimentary experimentation. The Edwin Smith Papyrus, dating to ancient Egypt, offers a remarkable compendium of surgical procedures and anatomical observations, treating medical conditions with a degree of pragmatism. Similarly, Hippocratic medicine in ancient Greece, while acknowledging divine influences, emphasized clinical observation, diagnosis, and prognosis.

The Interplay of Science, Philosophy, and Religion

In many ancient societies, science, philosophy, and religion were not separate domains. Instead, they often formed a tripartite unity, each informing and influencing the others. The search for understanding the universe was intrinsically linked to understanding humanity’s place within it and the divine forces believed to govern existence.

Cosmological Models and Divine Order

Ancient cosmologies were elaborate narratives that sought to explain the origin, structure, and sustenance of the universe. These models frequently attributed cosmic phenomena to the actions of deities or the manifestation of a divine will. For example, the geocentric model, prevalent for centuries, with Earth at the center, was often congruent with religious doctrines that placed humanity at the pinnacle of creation.

Early Natural Philosophy

Greek philosophers like Thales, Anaximander, and Empedocles, often labeled as “natural philosophers,” began to seek rational explanations for natural phenomena, attempting to move beyond purely mythological accounts. They proposed fundamental elements and forces that governed the universe, challenging traditional explanations and laying the groundwork for more empirical approaches. This shift, however, did not necessitate a complete rejection of the divine, but rather sought to understand the mechanisms through which the divine operated.

Throughout history, the suppression of ancient scientific knowledge by religious institutions has significantly impacted the progress of human understanding. An insightful article that delves into this topic is available at Real Lore and Order, which explores how various religious doctrines have often conflicted with emerging scientific ideas, leading to the stifling of intellectual inquiry and the persecution of those who dared to challenge established beliefs. This historical tension between faith and reason continues to resonate in contemporary discussions about the role of religion in science and education.

Emerging Tensions: The Seeds of Suppression

As scientific inquiry began to develop its own methodologies and to generate conclusions that sometimes diverted from established religious narratives, tensions arose. These tensions were not always overt or immediately destructive, but they represented the brewing storm that could, and often did, lead to suppression.

Challenging Anthropocentric and Theocentric Worldviews

The scientific pursuit of understanding the natural world, driven by observation and reason, occasionally produced findings that disturbed the established order of how humans perceived their place in the universe or the nature of the divine.

Heliocentric Theories and the Earthly Realm

The idea that the Earth was not the static, central point of the cosmos, as proposed by some early thinkers like Aristarchus of Samos, directly challenged the prevailing geocentric model. This model was not merely a scientific hypothesis; it was deeply interwoven with theological understandings that elevated humanity and Earth to a privileged, central position in God’s creation. To suggest otherwise could be interpreted as an affront to divine wisdom and human significance.

Questions of Divine Intervention and Natural Law

As natural philosophers began to identify patterns and regularities in the universe, suggesting the existence of natural laws, this could be seen as diminishing the role of constant divine intervention. If events could be explained by predictable processes, the need for ongoing supernatural action might appear less pronounced, potentially undermining a faith system that relied heavily on divine providence and miracles.

The Power of Established Religious Institutions

Religious institutions, by their very nature, invested heavily in maintaining their authority and the coherence of their doctrines. When scientific ideas threatened this coherence, institutions often acted to protect their position.

Guardians of Orthodoxy and Truth

Religious authorities often saw themselves as the ultimate custodians of truth and morality. Any knowledge that contradicted their sacred texts or pronouncements was viewed as heretical and potentially dangerous to the spiritual well-being of the populace. This sense of responsibility, however well-intentioned, could manifest as a rigid adherence to dogma, leaving little room for dissenting scientific ideas.

Maintaining Social and Political Control

In many ancient societies, religious authority was intertwined with political power. The clergy often held significant influence in governance, and the established religious order was a cornerstone of social stability. Scientific ideas that questioned fundamental tenets could destabilize this order, and therefore, faced opposition not just on theological grounds, but also as a threat to the existing power structures.

Case Studies of Religious Suppression

While the complexities of ancient societies make definitive pronouncements difficult, several historical examples offer compelling evidence of religious suppression impacting scientific advancement. These instances serve as cautionary tales, illustrating the human tendency to resist change when it challenges deeply held beliefs.

The Fate of Greek Natural Philosophy

The intellectual ferment of ancient Greece, a cradle of both philosophy and early scientific thought, was not immune to the forces of suppression, albeit often more subtle than outright persecution.

The Case of Anaxagoras

Anaxagoras, a pre-Socratic philosopher, was exiled from Athens around 450 BCE. While the precise reasons are debated, a significant factor cited by ancient sources was his controversial assertion that the sun was a molten mass and the moon was made of earth. These ideas conflicted with prevailing mythological explanations and possibly threatened the religious sensibilities of a city that venerated celestial bodies as divine. His view that celestial objects were neither gods nor divine beings, but rather natural phenomena, was a profound challenge.

The Trial of Socrates

Although Socrates was primarily a philosopher, his relentless questioning of accepted norms, including religious and ethical beliefs, ultimately led to his condemnation and execution. While his condemnation was officially for impiety and corrupting the youth, his critiques of traditional religious beliefs and his insistence on reason over superstition likely played a significant role. His method, an intellectual probe, was perceived as a threat to the established order, much like an unwelcome scientific discovery.

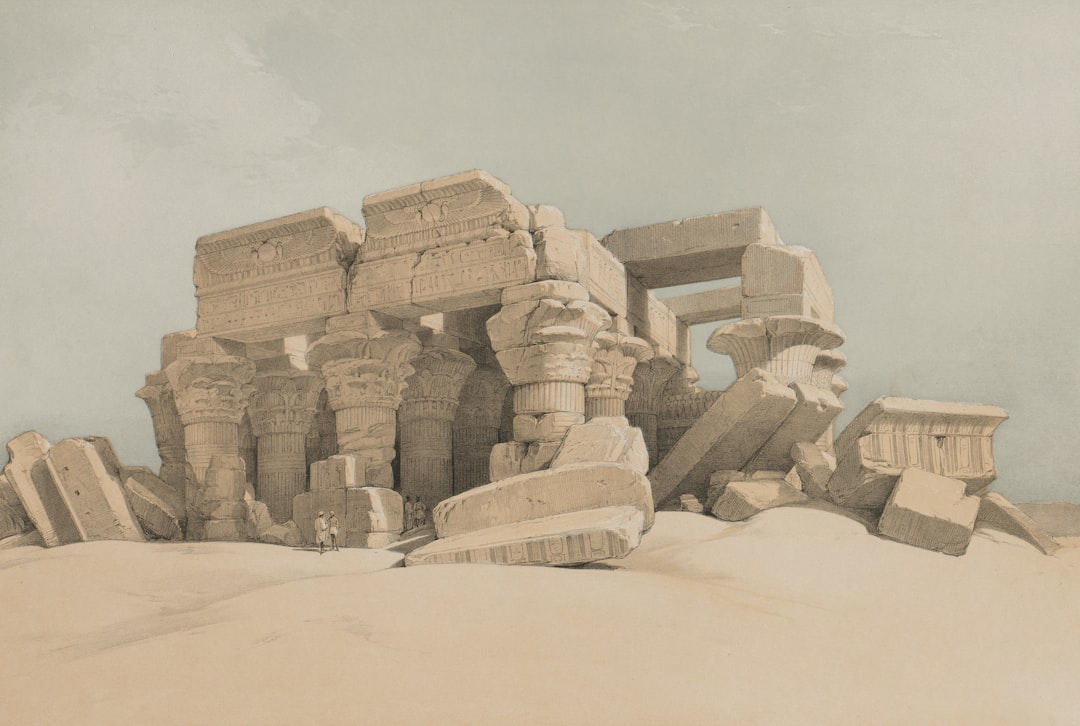

The Bibliotheca Alexandrina and its Decline

The Bibliotheca Alexandrina, a beacon of ancient knowledge, represented a monumental effort to collect and preserve scientific and literary works. Its eventual decline, however, can be linked to the shifting religious and political landscape, creating an environment less conducive to secular scientific pursuits.

The Burning of the Library

The destruction and decline of the Bibliotheca Alexandrina are attributed to various events over centuries, including accidental fires and deliberate acts of destruction. While the exact causes and the extent of the damage are debated among historians, some accounts link its demise to religious-political upheaval. The rise of Christianity and later the rise of Islam, as dominant religious forces, created an environment where the vast collection of pagan and scientific texts within the library may have been viewed with suspicion or hostility by certain factions.

The Shift in Intellectual Focus

As Christianity gained prominence in the Roman Empire, and later as Islamic empires fostered their own intellectual traditions, the emphasis within centers of learning began to shift. While these new traditions were often rich in scientific discovery, they also emerged from distinct religious frameworks. The secular, encyclopedic ambition of the Alexandrian library, which sought to encompass all knowledge regardless of its origin, may have been less valued in a world increasingly defined by religious allegiance. The library’s treasures, containing vast amounts of non-Christian knowledge, became vulnerable in an era where religious orthodoxy was paramount.

Suppression in the Context of Religious Conversion

The widespread adoption of new religions often involved a forceful suppression of pre-existing beliefs and practices, which naturally included the scientific knowledge associated with those traditions.

The Demise of Hellenistic Science under Christianity

The late Roman Empire witnessed the ascendant power of Christianity. As Christianity became the dominant religious ideology, pagan temples were destroyed, and pagan intellectual traditions, often intertwined with scientific inquiry, were actively suppressed. The Neoplatonist Academy in Athens, a significant center of scientific and philosophical learning, was closed by the Christian Emperor Justinian in 529 CE, marking a symbolic end to a long era of ancient philosophical and scientific inquiry. The logic here was simple: if the old gods and their attendant explanations were false, then the knowledge derived from them was also suspect.

The Abbasid Caliphate and the “Golden Age” of Islam

While the Islamic world is often celebrated for its “Golden Age” of scientific advancement, this era was not without its internal tensions between religious doctrine and scientific exploration. The translation movement, which brought vast amounts of Greek, Persian, and Indian scientific texts into Arabic, initially fostered a period of immense scientific progress. However, later theological debates, particularly concerning the Mu’tazila school of rationalist theology and its subsequent suppression, illustrate the inherent challenge of reconciling revealed truth with empirical observation. The Ash’ari school, which gained prominence, emphasized divine omnipotence in a way that sometimes saw natural causation as secondary to God’s will, potentially hindering a fully mechanistic understanding of the universe. This wasn’t a complete halt to science, but a subtle redirection and a reinforcement of theological boundaries.

Mechanisms and Motivations for Suppression

The forces that drove religious suppression of ancient science were varied and often interwoven. Understanding these mechanisms and motivations is key to comprehending the phenomenon.

Appeals to Authority and Dogma

The established religious texts and the pronouncements of religious leaders served as potent tools for silencing dissenting scientific voices.

Scripture as the Ultimate Arbiter

In many societies, sacred scriptures were considered the ultimate source of truth, divinely revealed. Any scientific hypothesis that contradicted these texts was not merely an intellectual disagreement; it was a challenge to divine authority. The Bible, the Quran, and other religious texts provided cosmologies, historical accounts, and explanations of natural phenomena that, when interpreted literally, could conflict with scientific observation.

The Power of the Priesthood

Religious leaders, as interpreters of sacred texts and mediators between humanity and the divine, wielded considerable influence. Their pronouncements could validate or invalidate new ideas. When scientific inquiry threatened their authority or the established worldview they propagated, they possessed the means and motivation to actively suppress it, acting as gatekeepers of acceptable knowledge.

Fear of the Unknown and the Loss of Control

New scientific ideas, especially those that challenged deeply ingrained beliefs, could evoke significant fear and anxiety within a population. This fear often translated into a demand for control and the suppression of potentially disruptive knowledge.

The Unsettling Nature of New Discoveries

The heliocentric model, for example, was deeply unsettling. It displaced humanity from the center of the cosmos, a position that provided a sense of purpose and importance. Such a shift in understanding was akin to pulling the rug out from under a familiar and comforting reality. Similarly, the identification of natural causes for phenomena previously attributed to divine wrath or intervention could undermine a sense of divine control and predictability that many found reassuring.

Maintaining Social Order and Stability

Religious dogma often served as the glue that held societies together, providing a shared moral framework and a sense of collective identity. Scientific ideas that promised to dismantle this framework, even if they offered greater accuracy, were often viewed as a threat to social cohesion and stability. The desire to maintain the status quo and prevent social upheaval could be a powerful motivator for religious authorities to suppress scientific challenges.

Throughout history, the suppression of ancient science by religious institutions has often stifled intellectual progress and innovation. A compelling examination of this phenomenon can be found in an article that discusses how various religious doctrines have historically clashed with scientific inquiry, leading to the marginalization of groundbreaking ideas. For those interested in exploring this topic further, the article offers valuable insights into the complex relationship between faith and reason. You can read more about it in this detailed analysis.

The Long Shadow of Suppression

| Aspect | Description | Example | Impact on Science |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time Period | Medieval Era (5th to 15th century) | European Middle Ages | Delayed scientific progress in Europe |

| Religious Institution | Roman Catholic Church | Inquisition and censorship | Suppression of heliocentric theory and other ideas |

| Suppressed Science | Astronomy, Anatomy, and Natural Philosophy | Galileo Galilei’s heliocentrism | Hindered acceptance of scientific methods |

| Methods of Suppression | Censorship, Trials, Book Burnings | Trial of Galileo (1633) | Discouraged open scientific inquiry |

| Long-term Effects | Shift of scientific centers to Islamic world and later Renaissance Europe | Preservation of Greek texts by Islamic scholars | Delayed but eventual revival of science |

The religious suppression of ancient science did not merely represent a temporary halt to progress; it cast a long shadow, influencing the trajectory of intellectual development for centuries. The impact of these suppressive forces is a crucial, albeit often uncomfortable, chapter in the story of human knowledge.

The Loss of Knowledge and Innovation

When scientific inquiry is stifled, the natural consequence is the loss of valuable knowledge and the impediment of potential innovation. Entire fields of study can be marginalized, and promising lines of research may be abandoned.

The Destruction of Texts and Laboratories

The deliberate destruction of ancient libraries, the burning of scientific texts, and the persecution of scholars represent a direct and devastating form of suppression. Each act of destruction is akin to extinguishing a unique star in the night sky of human understanding, leaving a void that may never be filled. The loss of the Antikythera mechanism, a complex astronomical calculator from ancient Greece, or the detailed anatomical studies that may have been lost in the destruction of the Library of Alexandria, are poignant examples of what can be lost.

Stifled Curiosity and the Chilling Effect

Beyond outright destruction, the oppressive climate created by religious suppression could engender a profound chilling effect on intellectual curiosity. Scholars might self-censor, fearing persecution or ostracization. This fear could lead to a stagnation of thought, where minds accustomed to questioning and exploring new avenues are instead channeled into safer, more orthodox avenues of inquiry, if at all. The vibrant intellectual life of certain periods could be replaced by a more muted, conformist intellectual environment.

Cycles of Rediscovery and Re-engagement

The story of science is also one of resilience and rediscovery. Despite periods of suppression, the human drive to understand has often found ways to resurface, leading to the re-engagement with lost knowledge and the eventual overcoming of dogmatic barriers.

The Role of Preservation and Translation

Remarkably, some ancient scientific knowledge survived suppression through careful preservation and translation by scholars in different cultures and eras. The Islamic world, for instance, played a crucial role in preserving and building upon Greek scientific traditions during periods when such knowledge was less accessible or even actively suppressed in parts of Europe. This act of intellectual custodianship allowed crucial ideas to endure, waiting for the right intellectual climate for their revival.

The Eventual Triumph of Reason and Evidence

Ultimately, the power of empirical observation and logical reasoning has often proven more enduring than rigid dogma. While religious suppression could delay progress, it could rarely extinguish the flame of inquiry permanently. Over time, as societies evolved and new intellectual paradigms emerged, the evidence-based approach of science gradually gained recognition, leading to the dismantling of age-old doctrines and the re-establishment of scientific inquiry on firmer footing. The Renaissance and the Scientific Revolution in Europe are testaments to this cyclical triumph of reason over imposed limitations.

The history of religious suppression of ancient science is a somber reminder that the pursuit of knowledge is not always a smooth, unfettered journey. It is a narrative of courage by those who dared to question, resilience in the face of opposition, and the enduring power of human curiosity to illuminate the darkest corners of ignorance. Understanding these historical struggles is not merely an academic exercise; it is crucial for safeguarding the present and future of scientific endeavor, ensuring that the rivers of discovery are allowed to flow freely, unburdened by the dams of dogma and fear.

FAQs

What is meant by the suppression of ancient science by religious institutions?

The suppression of ancient science by religious institutions refers to historical instances where religious authorities opposed, censored, or restricted scientific ideas, discoveries, or teachings that conflicted with their doctrines or beliefs.

Which ancient scientific ideas were commonly suppressed by religious institutions?

Ideas such as heliocentrism (the Sun-centered solar system), evolutionary theory, and certain medical or astronomical knowledge were often suppressed because they challenged prevailing religious views about the universe and human existence.

Can you provide examples of religious institutions suppressing scientific knowledge?

One notable example is the Catholic Church’s opposition to Galileo Galilei’s support of heliocentrism in the 17th century. Similarly, some religious authorities rejected or censored works by ancient scientists like Aristarchus or early evolutionary thinkers.

Did all religious institutions suppress ancient science?

No, not all religious institutions suppressed scientific knowledge. In some cases, religious scholars preserved and advanced scientific understanding, such as during the Islamic Golden Age when Muslim scholars translated and expanded upon ancient Greek scientific texts.

What impact did the suppression of ancient science have on scientific progress?

Suppression often delayed the acceptance and development of scientific ideas, limiting open inquiry and debate. However, despite these challenges, many scientific concepts eventually gained acceptance and contributed to modern science.