The intricate dance of ancient technologies often leaves modern observers in awe, particularly when encountering devices that suggest a level of engineering sophistication seemingly out of place in their historical context. Among these marvels, differential gears and early forms of mechanical memory stand as testaments to the ingenuity of ancient civilizations. These mechanisms, far from being mere curiosities, represent fundamental principles of computation and mechanical control, illuminating pathways for understanding the evolution of technology itself. Their study is not merely an archaeological exercise but a deep dive into the very roots of mechanical intelligence.

The Antikythera Mechanism, an unparalleled example of ancient Greek engineering, serves as the prime exhibit when discussing ancient differential gears. Discovered in a shipwreck off the coast of the Greek island of Antikythera in 1901, this corroded bronze device has confounded and fascinated researchers for over a century. Its complexity, initially underestimated, has since been revealed through meticulous X-ray tomography and astronomical modeling, showcasing an astonishing level of mechanical sophistication.

Unveiling the Mechanism’s Purpose

Initially, the device’s function was a mystery, its gears and plates fused by centuries of calcification. However, as layers of marine accretion were peeled back, and internal structures were gradually revealed, its true purpose began to crystallize. The Antikythera Mechanism was not merely an astronomical clock but a sophisticated analog computer, designed to predict astronomical positions and eclipses with remarkable accuracy. It integrated knowledge of the movements of the Sun, Moon, and planets known at the time into a complex, interlinked system of gears.

The Role of Differential Gearing

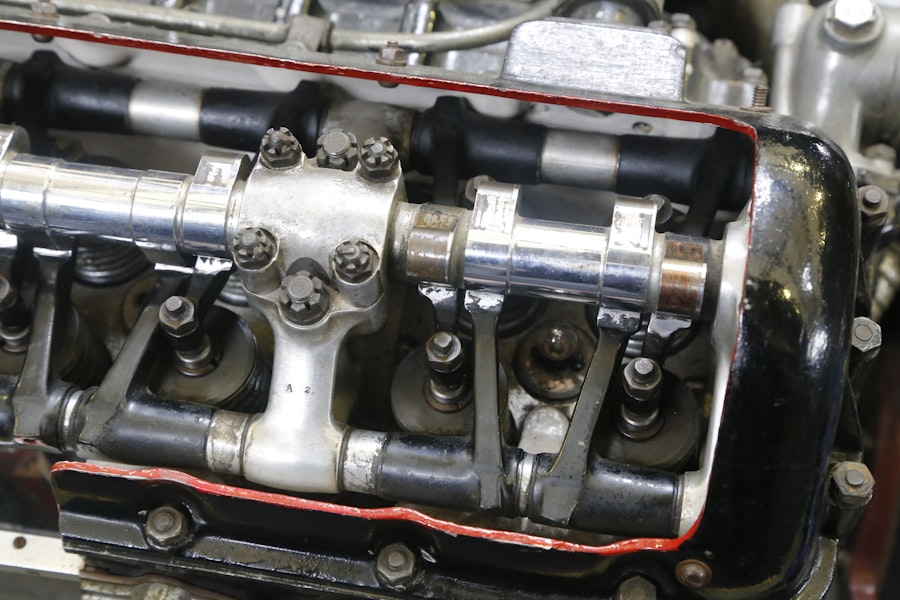

At the heart of the Antikythera Mechanism’s predictive capabilities lies a sophisticated differential gear system. This system, unlike simple gear trains that transmit motion in a fixed ratio, allows for the addition or subtraction of rotational inputs, resulting in an output that reflects the sum or difference of these inputs. In the context of the Antikythera Mechanism, this was crucial for modeling the anomalous motion of the Moon.

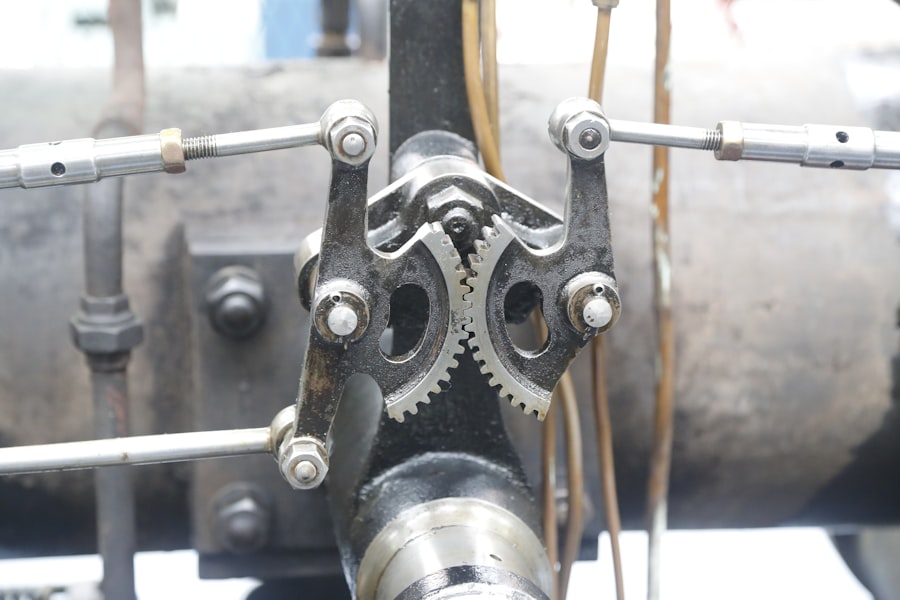

- Lunar Anomaly: The Moon’s orbital speed is not constant; it accelerates and decelerates due to its elliptical orbit. Ancient Greek astronomers, notably Hipparchus, were aware of this phenomenon. The Antikythera Mechanism incorporated an ingenious differential gear train to simulate this varying speed, driving a pointer that accurately displayed the Moon’s changing position against the background stars. This particular differential arrangement involved a series of gears that effectively added two rotations, one representing the average lunar motion and another representing the periodic fluctuation, to produce a composite output that mirrored the Moon’s observed non-uniform motion. This was a triumph of mechanical ingenuity, anticipating concepts that would not be formally explored in mechanical engineering for another millennium and a half.

- Mercury’s Inferior Conjunction: While the primary and most clearly understood application of the differential gear in the Antikythera Mechanism was the lunar anomaly, some researchers speculate about its potential use in modeling the more complex, retrograde motions of other planets. The intricate interconnections of the gears suggest a capacity for handling multiple astronomical phenomena, presenting a compelling argument for its advanced design. The exact replication of every known planetary anomaly within the surviving fragments remains a subject of ongoing debate, yet the presence of this foundational computational element is undeniable.

Ancient differential gears and mechanical memory are fascinating topics that highlight the ingenuity of early engineering. A related article that delves deeper into these subjects can be found at Real Lore and Order, where the intricate designs and applications of ancient mechanisms are explored. This resource provides valuable insights into how these early inventions laid the groundwork for modern technology, showcasing the remarkable capabilities of ancient civilizations in creating complex mechanical systems.

Mechanical Memory: Storing and Retrieving Information

Beyond predictive calculations, ancient engineers also grappled with the problem of storing and retrieving information mechanically – a nascent form of what we now call mechanical memory. While not as explicit as modern digital memory, these systems encoded data within their physical structure, allowing for complex sequences or pre-programmed responses.

Pre-programmed Automation: Ctesibius’s Water Clocks

Ctesibius of Alexandria, a Hellenistic inventor from the 3rd century BCE, spearheaded advancements in pneumatics and hydraulics, among which his elaborate water clocks stand out. These devices were not merely timekeepers but often incorporated intricate internal mechanisms that could trigger events and display complex information, demonstrating a form of mechanical memory.

- Automata and Timed Sequences: Ctesibius’s water clocks were renowned for their automata, which could be programmed to perform specific actions at predetermined intervals. These might include figures rising or falling, trumpets sounding, or even water pouring from spouts. The programming was achieved through the careful shaping of cams, the arrangement of pegs on rotating drums, or the calibrated flow of water, all of which encoded a sequence of events into the clock’s physical architecture. This encoding was essentially a form of mechanical memory, where the physical configuration of the device itself stored the instructions for its operation.

- Displaying Astronomical Data: Some of these sophisticated water clocks also displayed astronomical phenomena or calendrical information. This required internal mechanisms that could “remember” the relationships between different celestial cycles. For instance, a dial that showed the constellations visible at a particular hour would have its rotation tied to the main timekeeping mechanism, with the constellations themselves engraved onto the dial, effectively a static form of memory. The continuous interaction of gears and levers within these clocks was a testament to the fact that even seemingly simple mechanical principles could be combined to store and recall complex information.

The Automata of Heron of Alexandria

Heron of Alexandria, who lived in the 1st century CE, built upon Ctesibius’s foundations, developing an extraordinary range of automata described in his treatise Automata. These devices featured ingenious mechanisms that relied heavily on pre-programmed sequences and mechanical feedback, embodying a more dynamic form of mechanical memory.

- Cam-Driven Sequences: Many of Heron’s automata, such as his self-opening temple doors or his mechanical theatrical productions, utilized elaborate cam-driven mechanisms. Cams, precisely shaped rotating or sliding pieces, would interact with levers to trigger a sequence of actions. The shape of each cam effectively “remembered” the desired motion, translating rotational input into complex linear or oscillating movements. This was a direct form of mechanical programming, where the physical geometry of the cam dictated the output sequence.

- Weight-Driven Automation: Heron also employed falling weights and siphons to power his automata, creating mechanisms that could sustain operations over a period of time, with internal components managing the sequence of events. For example, his temple doors, which opened and closed automatically when a fire was lit on an altar, involved a complex interplay of air pressure, levers, and water displacement, all orchestrated by a precisely calibrated system. The arrangement of these components constituted the device’s memory, guiding its actions in response to external stimuli. In essence, the entire system “recalled” its pre-programmed behavior as various triggers were met.

Beyond the Greek World: Other Early Forms

While the Antikythera Mechanism firmly establishes the Greeks’ prowess in differential gearing, and Ctesibius and Heron demonstrate early mechanical memory, it is important to acknowledge that the seeds of such ingenuity were sown across various ancient civilizations. The independent development of similar concepts showcases a shared human drive to understand and control the environment through mechanical means.

Chinese Mechanical Clocks and Astronomical Instruments

In ancient China, sophisticated mechanical clocks emerged during the Tang and Song dynasties, most notably exemplified by the clock tower built by Su Song in the 11th century. This massive astronomical clock featured an escapement mechanism and drove various display panels and automata, illustrating an independent trajectory in mechanical design.

- Water-Powered Escapements: Su Song’s clock tower employed a complex water-powered escapement system that regulated the flow of time. This system, itself an intricate dance of weights, levers, and scoops, controlled a series of display mechanisms that showed the time of day, the phases of the moon, and the positions of celestial bodies. The construction of the escapement and the interconnected astronomical displays presented a large-scale example of integrated mechanical memory, where the components collectively remembered and presented temporal and celestial information.

- Automated Figures: The clock tower also featured automated figures that would emerge from doors at specific times, striking drums and bells to announce the hour. This was a direct parallel to the automata of Heron and Ctesibius, showcasing a similar conceptual approach to engineering pre-programmed mechanical sequences. The cam-like structures and lever systems that controlled these figures again embodied a form of stored mechanical information.

Islamic Golden Age Astronomical Instruments

During the Islamic Golden Age, scholars and engineers made significant contributions to astronomy and instrumentation. Their astrolabes, quadrants, and celestial globes were highly advanced, often incorporating intricate gearing and computational aids that approached the sophistication seen in the Antikythera Mechanism, albeit with different design philosophies.

- Planetary Equatoria: Islamic astronomers developed planetary equatoria, mechanical analog computers designed to determine the longitudes of planets. While direct evidence of differential gearing replicating the complexity of the Antikythera Mechanism is less clear-cut, these devices demonstrated incredibly precise gear trains and computational techniques to model celestial movements. The intricate layouts and connections within these equatoria represented a sophisticated form of data storage, where the physical configuration of the instrument itself embodied astronomical knowledge, acting as a form of analog memory.

- Automated Calendar Devices: Some Islamic scholars also created elaborate calendar devices that could display temporal information, lunar phases, and astrological data. These mechanisms, often driven by water or weights, embedded calendrical rules and astronomical cycles into their mechanical structure. The positioning of gears and the design of rotating plates inherently “remembered” the relationships between different temporal units and celestial events, making them powerful tools for both prediction and display.

Engineering Principles and Modern Resonances

The study of ancient differential gears and mechanical memory is not merely a historical curiosity. It offers profound insights into fundamental engineering principles that continue to resonate in contemporary technology. These ancient devices, in their essence, were analog computers, demonstrating solutions to complex problems using purely mechanical means.

The Foundation of Analog Computing

The differential gear, as exemplified by the Antikythera Mechanism, is a cornerstone of analog computing. It allows for the real-time addition and subtraction of physical quantities (in this case, rotations), laying the groundwork for more complex analog calculators and control systems. Its existence in antiquity challenges the common perception that sophisticated computational machinery is a relatively recent invention, revealing a continuous lineage of innovation stretching back millennia.

- Beyond Simple Gearing: The conceptual leap from a simple gear train (which enforces a fixed ratio of motion) to a differential gear (which allows for dynamic input addition/subtraction) is significant. It represents a move from mere transmission of motion to actual computation with motion. This distinction is crucial for understanding the intellectual gravity of the Antikythera Mechanism, as it embodies a true computational engine.

- Precursor to Control Systems: Differential gears are also fundamental components in many modern control systems, from the differentials in automobiles that allow wheels to spin at different speeds during turns, to complex industrial machinery. Studying their ancient origins provides a historical perspective on their enduring utility and the universality of certain mechanical solutions to recurring engineering challenges.

The Genesis of Programmability

The automata of Ctesibius and Heron, and the automated mechanisms within Chinese clocks, represent the early stirrings of programmability. By encoding sequences of actions into cams, levers, and mechanical linkages, these engineers created devices that could perform complex tasks autonomously, effectively “remembering” a set of instructions.

- Hardware-Encoded Software: In a metaphorical sense, these ancient devices featured “hardware-encoded software.” The physical shape of a cam was the algorithm, and the mechanical interaction was the execution of that algorithm. This paradigm, while vastly different from modern digital programming, highlights the enduring human desire to automate tasks and imbue machines with the ability to follow instructions.

- Enduring Design Principles: The principles of cam design, linkage mechanisms, and feedback loops derived from these ancient automata are still actively employed in various forms of modern machinery. From internal combustion engines to robotic appendages, the clever manipulation of physical forms to dictate movement and sequence is a testament to the timeless nature of these foundational engineering ideas.

Ancient differential gears and mechanical memory have long fascinated historians and engineers alike, as they represent significant advancements in early technology. A related article explores the intricate designs and applications of these ancient mechanisms, shedding light on their impact on modern engineering principles. For those interested in delving deeper into this topic, you can read more about it in this insightful piece on mechanical innovations. Understanding these early inventions not only highlights human ingenuity but also illustrates the foundational concepts that continue to influence contemporary machinery.

The Ongoing Journey of Discovery

| Artifact | Period | Location | Type of Mechanism | Function | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antikythera Mechanism | Circa 100 BCE | Greece | Differential Gears | Astronomical calculator predicting celestial positions | Earliest known use of differential gearing and mechanical memory |

| Al-Jazari’s Castle Clock | 1206 CE | Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) | Mechanical Gears with Memory Components | Automated timekeeping with programmable features | Early example of mechanical memory and programmable machinery |

| Su Song’s Astronomical Clock Tower | 1094 CE | China | Escapement and Gear Mechanisms | Timekeeping and astronomical observations | Incorporated early mechanical memory for automating functions |

| Hero of Alexandria’s Automata | 1st Century CE | Alexandria, Egypt | Mechanical Gears and Cams | Automated theatrical devices and fountains | Demonstrated early principles of mechanical control and memory |

The study of ancient differential gears and mechanical memory is an ongoing journey. New archaeological discoveries, refined analytical techniques, and collaborative interdisciplinary research continue to shed light on the capabilities and limitations of these extraordinary ancient technologies. The Antikythera Mechanism, for example, is still revealing secrets, with researchers continually re-evaluating its potential functionalities and the depth of knowledge encoded within its intricate gears.

By examining these ancient mechanical wonders, we gain a deeper appreciation for the intellectual prowess of our ancestors. They remind us that the human quest for understanding, prediction, and control through technology is not a recent phenomenon but a fundamental impulse that has driven innovation for millennia. These mechanisms are not merely artifacts; they are echoes of ancient brilliance, whispering tales of ingenuity across the vast expanse of time, inviting us to decode their remaining secrets.

FAQs

What are ancient differential gears?

Ancient differential gears are mechanical devices used in early machinery to allow two shafts to rotate at different speeds while transmitting power. They date back to ancient civilizations and were fundamental in the development of complex mechanical systems.

How were differential gears used in ancient times?

In ancient times, differential gears were primarily used in devices such as chariots and early automata to manage the distribution of rotational force. They enabled wheels or components to move at different speeds, improving maneuverability and mechanical function.

What is mechanical memory in the context of ancient technology?

Mechanical memory refers to the ability of a mechanical system to store and recall information through its physical configuration or movement. In ancient technology, this concept was applied in devices that could record or repeat sequences of motions without electronic components.

Which ancient civilizations contributed to the development of differential gears?

Civilizations such as the Greeks, Romans, and Chinese made significant contributions to the development of differential gears. Notable examples include the Antikythera mechanism from ancient Greece, which incorporated complex gear systems.

Why are ancient differential gears and mechanical memory important to modern engineering?

Ancient differential gears and mechanical memory systems laid the groundwork for modern mechanical engineering by demonstrating early principles of motion control and information storage. Understanding these ancient technologies helps engineers appreciate the evolution of mechanical design and inspires innovation in contemporary machinery.