The practice of manuscript recycling, an often overlooked facet of ancient and medieval scholarship, represents a pragmatic and ingenious approach to resource management and knowledge preservation. Scribes throughout millennia, faced with material scarcity, economic constraints, and the constant need for writing surfaces, routinely repurposed existing documents. This phenomenon, far from being a mere act of destruction, was a sophisticated process that provided a second life for countless texts, consciously or unconsciously preserving fragments of cultural heritage that might have otherwise been lost to history.

The decision to reuse a manuscript was rarely arbitrary. Economic and practical considerations fundamentally underpinned this widespread practice. Writing materials, whether papyrus, parchment, or paper, were commodities that required significant resources to produce.

The Cost of Writing Surfaces

Manufacturing a new parchment codex, for instance, involved an extensive process that began with animal husbandry. The hides of sheep, goats, or calves were carefully prepared, a labor-intensive endeavor requiring cleaning, de-hairing, stretching, and scraping to achieve a suitable writing surface. This process was time-consuming and demanded skilled labor, making parchment a valuable commodity. Papyrus, though less labor-intensive in its preparation, was geographically limited in its production, primarily to Egypt, making it an import commodity in many regions and thus subject to trade routes and political stability. Consequently, the cost of acquiring virgin writing material was often prohibitive, especially for institutions or individuals with limited budgets.

The Scarcity of Raw Materials

Beyond cost, the sheer availability of raw materials played a significant role. Deforestation for papyrus production, or the need for large herds for parchment, could create shortages. Recycling offered a sustainable alternative, a way to circumvent these material limitations. In a world without industrial-scale production, every scrap of usable material was precious. Imagine a modern society where every sheet of paper had to be handcrafted, and you begin to grasp the inherent value ascribed to these ancient writing surfaces.

The Lifecycle of a Manuscript

Understanding the complete lifecycle of a manuscript, from its creation to its potential dissolution or repurposing, reveals the pragmatic choices made by scribes. A manuscript might serve its primary purpose for a period, perhaps as a liturgical text, a legal document, or a scholarly treatise. However, as its relevance waned, its condition deteriorated, or new, more current texts emerged, its value shifted from its content to its material form. It became a latent resource, waiting to be reactivated. This cyclical view of manuscript life is crucial to understanding the rationale behind recycling.

In exploring the fascinating practices of ancient scribes, one can gain insight into how they recycled technical manuscripts to conserve resources and preserve knowledge. This process not only highlights the ingenuity of these early scholars but also reflects the value they placed on the written word. For a deeper understanding of this topic, you can read a related article that delves into the methods and implications of manuscript recycling in ancient times at this link.

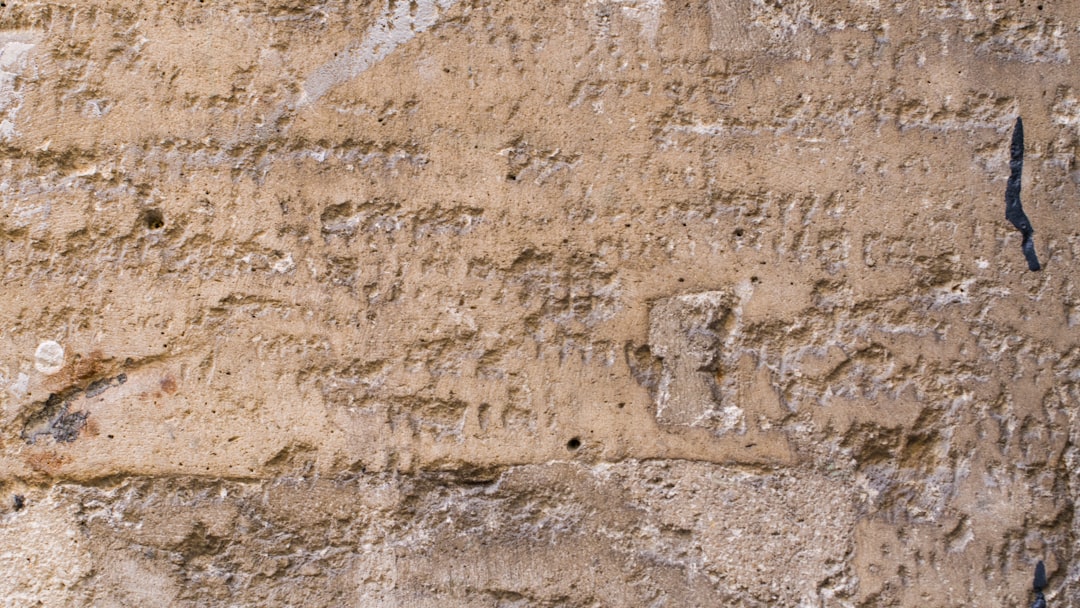

Palimpsests: Whispers from the Past

The palimpsest, a manuscript from which earlier writing has been erased to make way for new text, stands as the most eloquent testament to early manuscript recycling. These layered documents are invaluable historical artifacts, offering a physical manifestation of this practice.

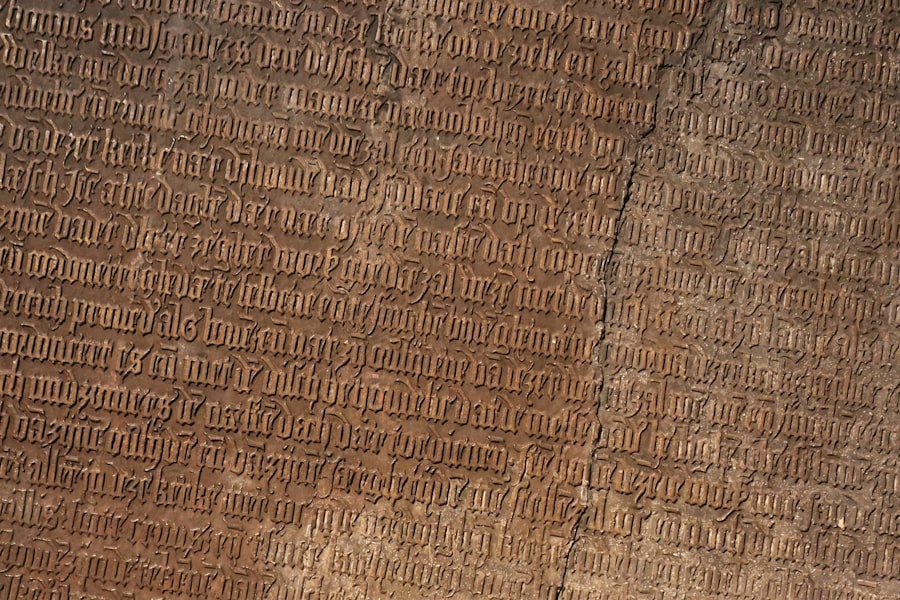

The Process of Eradication and Rewriting

The creation of a palimpsest was a labor-intensive undertaking. For parchment, the existing ink was typically scraped off using a pumice stone or a sharp knife, and then the surface might be washed or bleached to further remove traces of the previous writing. However, the complete removal of ink was often imperfect, leaving faint but readable under-texts – the “ghost” of the original content. On papyrus, the process was even more challenging, often involving washing or simply writing over faded ink with a darker, thicker layer. This imperfection, ironically, has become a boon for modern scholarship.

Unveiling Hidden Knowledge

The discovery and decipherment of palimpsests have been instrumental in recovering lost literary and historical works. Scholars employ advanced imaging techniques, such as multispectral imaging and ultraviolet light, to enhance the visibility of these under-texts. These techniques illuminate the faint traces of ink, allowing for a digital reconstruction of the original manuscript. The Archimedes Palimpsest, containing unique mathematical treatises by the ancient Greek mathematician, and the Syra-Sinaiticus palimpsest, revealing a fifth-century Syriac translation of the Gospels, are prime examples of the profound discoveries made possible by studying these layered documents. Each palimpsest is a time capsule, offering glimpses into intellectual landscapes long past.

The Value of Under-Texts

The under-text of a palimpsest often predates the over-text, providing a window into earlier periods of scholarship, linguistic forms, and textual traditions. The overwritten text is frequently considered of lesser value or was superseded by newer copies, while the underlying text, once thought lost, often represents unique or exceptionally early witnesses to important works. This highlights a fascinating dynamic: what one generation deemed expendable, another generation, millennia later, considers a priceless archeological treasure.

Beyond Palimpsests: Other Forms of Manuscript Repurposing

While palimpsests represent the most overt form of manuscript recycling, scribes employed various other methods to give new life to old documents, extending their utility and ensuring no valuable material went to waste.

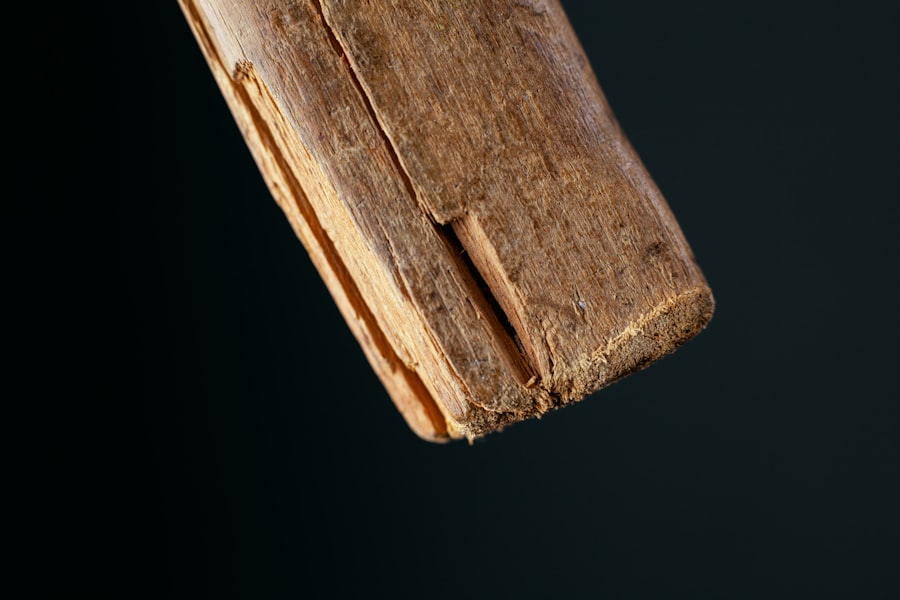

Binding Fragments

Old manuscripts, deemed no longer useful in their entirety, were often dismembered and their leaves or fragments used as binding material for newer codices. These fragments could serve as reinforcing strips along the spine, pastedowns on the inner covers, or even as endleaves. The discovery of these binding fragments has yielded invaluable insights into the circulation of texts, the existence of otherwise lost works, and the physical characteristics of manuscripts from earlier periods. It’s akin to finding an ancient newspaper clipping reinforcing the spine of a modern book – a small, unexpected window into the past.

Cartonnage and Mummification

In ancient Egypt, papyrus was ingeniously recycled for practical purposes beyond simply overwriting. Cartonnage, a material made from layers of painted and plastered papyrus or linen, was extensively used for mummy masks and coffins. The papyrus used in cartonnage often comprised discarded administrative documents, literary texts, or personal letters. The meticulous unwrapping and analysis of these cartonnage layers have led to the recovery of numerous fragmented but significant ancient Egyptian texts, providing unique insights into daily life, administration, and literature. This method of recycling exemplifies a truly embedded and multifunctional approach to material usage.

Scrap Papers and School Exercises

Less formal but equally important was the repurposing of old manuscripts as “scrap paper” for notes, drafts, or school exercises. In scriptoria or monastic environments, where writing materials were at a premium, any available surface could be pressed into service. These marginalia or practice texts, though often dismissively regarded by earlier scholars, are now recognized as valuable sources for understanding scribal practices, pedagogical methods, and even the informal intellectual life of the time. They are the ancient equivalent of using the back of an old invoice for a grocery list.

The Cultural and Intellectual Implications of Recycling

The widespread practice of manuscript recycling had profound implications for the transmission of knowledge and the understanding of intellectual priorities in ancient and medieval societies.

Selective Preservation and Loss

The decision to reuse a manuscript was inherently a decision about selective preservation and, by extension, selective loss. Texts deemed less relevant, superseded, or simply out of fashion were more likely to become source material for palimpsests or binding fragments. This process, while pragmatic, inevitably shaped the corpus of texts that survived to the present day. We are, in essence, beneficiaries of a historical triage, where the “survivors” were sometimes deliberately chosen, and sometimes preserved purely by chance due to their material form being repurposed.

The Evolution of Textual Traditions

Recycling practices also played a role in the evolution of textual traditions. As older manuscripts were repurposed, new copies were often made with updated language, revised interpretations, or corrected errors. This process, while sometimes leading to the loss of original versions, also facilitated the continuous adaptation and refinement of texts to suit contemporary needs and understanding. It illustrates a dynamic interaction between content and its physical embodiment.

Insights into Scribal Culture

The study of recycled manuscripts provides invaluable insights into the daily lives, economic constraints, and intellectual priorities of scribes and the institutions they served. It reveals a culture of frugality and ingenuity, where every resource was maximized. The imperfections in erasure, the choice of texts to overwrite, and the content of the new texts all contribute to a richer understanding of the scribal environment. It paints a picture not of mere copyists, but of active participants in the intellectual and material economy of their age.

Ancient scribes often faced the challenge of limited resources, leading them to recycle technical manuscripts for new purposes. This practice not only conserved valuable materials but also allowed for the preservation and adaptation of knowledge across generations. For a deeper understanding of how these scribes managed to repurpose their work, you can explore a related article that delves into the fascinating methods they employed. To learn more about this intriguing aspect of historical manuscript production, visit this article.

Modern Scholarship and the Future of Manuscript Recycling Studies

| Metric | Description | Example | Impact on Manuscript Preservation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Palimpsest Frequency | Percentage of manuscripts reused by scraping or washing off original text | Approximately 10-15% of medieval manuscripts are palimpsests | Led to partial loss of original technical content but preserved some underlayers |

| Material Reuse Rate | Proportion of parchment or papyrus recycled for new manuscripts | Up to 30% of available writing materials in some monastic libraries were reused | Conserved scarce writing materials but caused degradation of original texts |

| Technical Content Retention | Extent to which original technical information was preserved after recycling | About 40% of technical diagrams and formulas remain partially legible in palimpsests | Allowed partial recovery of ancient scientific knowledge |

| Recycling Methods | Techniques used to erase or overwrite manuscripts | Scraping, washing, and overwriting with ink | Varied effectiveness; scraping often damaged original text more than washing |

| Time Period | Era when recycling of technical manuscripts was most prevalent | 5th to 12th centuries CE | Corresponded with scarcity of writing materials and shifts in scholarly focus |

Modern scholarship continues to unravel the complexities and hidden narratives embedded within recycled manuscripts. The fusion of traditional codicological expertise with cutting-edge scientific imaging techniques promises further revelations.

Advanced Imaging Technologies

Technological advancements, such as multispectral imaging, X-ray fluorescence analysis, and even artificial intelligence used for pattern recognition in faint scripts, are revolutionizing the decipherment of palimpsests and other reused materials. These tools allow scholars to peer beneath layers of ink and even beyond the surface of a page, virtually restoring lost texts with unprecedented clarity. The digital age provides a non-invasive means to interact with these delicate historical artifacts, ensuring their physical preservation while unlocking their intellectual content.

Ethical Considerations in Research

As our ability to extract information from these artifacts grows, so too does the need for careful ethical consideration. The destructive nature of previous methods, such as chemical treatments to enhance ink, has largely been replaced by non-invasive imaging. However, the balance between preserving the artifact and extracting its information remains a central concern, particularly for fragile items. The “reading” of a palimpsest or cartonnage fragment must be approached with the utmost respect for the physical integrity of the historical object.

The Broader Narrative of Resourcefulness

The ongoing study of manuscript recycling is not merely an academic exercise; it offers a compelling narrative of human resourcefulness and adaptability. It reminds us that across diverse cultures and time periods, the intelligent reuse of materials was not a peripheral activity but a vital component of cultural production and intellectual transmission. It underscores a fundamental human impulse to make the most of what is available, ensuring the continuity of knowledge even in the face of material limitations. The faint traces of ancient texts, brought back to life through modern technology, serve as a potent reminder of this enduring legacy.

FAQs

1. How did ancient scribes recycle technical manuscripts?

Ancient scribes often recycled technical manuscripts by scraping off the original text from parchment or papyrus and reusing the material to write new texts. This process, known as palimpsesting, allowed them to conserve valuable writing materials.

2. Why was recycling manuscripts important in ancient times?

Recycling manuscripts was important because writing materials like parchment and papyrus were expensive and scarce. By reusing these materials, scribes could save resources and continue producing new documents without the need for constant supply of fresh materials.

3. What types of technical manuscripts were commonly recycled?

Technical manuscripts that were recycled included scientific treatises, mathematical texts, medical manuals, and engineering documents. These texts were often overwritten with religious or literary works, reflecting changing priorities or the obsolescence of certain technical knowledge.

4. How do modern scholars study recycled manuscripts?

Modern scholars use advanced imaging techniques such as multispectral imaging and X-ray fluorescence to recover and read the erased or overwritten texts on recycled manuscripts. These technologies help reveal hidden layers of writing that are invisible to the naked eye.

5. What significance does the recycling of technical manuscripts have for historical research?

The recycling of technical manuscripts provides valuable insights into the transmission and preservation of knowledge in ancient cultures. It also helps historians understand which types of knowledge were valued or discarded over time, shedding light on cultural and intellectual history.