The civilization of Ancient Egypt, renowned for its pyramids, temples, and obelisks, stands as a testament to early human ingenuity and advanced engineering capabilities. For millennia, the construction techniques employed by the Egyptians have puzzled modern engineers and historians alike, inspiring various theories ranging from the plausible to the fantastical. This article examines the practical and theoretical underpinnings of Ancient Egyptian engineering, focusing on the methodologies, tools, and logistical strategies that facilitated the creation of their monumental structures. The objective is to provide a comprehensive overview of the technical prowess of this civilization, dispelling myths and highlighting verifiable facts through historical and archaeological evidence.

The construction of any complex structure necessitates meticulous planning, and the Ancient Egyptians were exemplary in this regard. Their monumental works were not haphazard constructions but rather the culmination of sophisticated design processes that integrated religious beliefs, celestial observations, and practical engineering principles.

Architectural Drawing and Surveying

Before a single stone was quarried, the entire project was conceptualized and documented. Architectural drawings, though few surviving examples exist, are evidenced by incised lines on plaster, papyri fragments, and ostraca. These rudimentary blueprints served as visual guides, depicting floor plans, elevations, and details of structural components.

- Grid Systems and Proportions: Egyptian architects utilized grid systems, often based on the cubit (approximately 52.3 cm), to scale their designs. This allowed for precise replication of forms and proportions, ensuring aesthetic harmony and structural integrity. The application of the golden ratio, phi (approximately 1.618), has been suggested in the proportions of structures such as the Great Pyramid, though definitive proof remains elusive and debated among scholars.

- Site Selection and Orientation: The selection of a construction site was not arbitrary. Factors such as proximity to quarries, stability of the bedrock, and ritualistic orientation were paramount. Many temples and pyramids were meticulously aligned with astronomical events, such as the solstices and equinoxes, or with specific celestial bodies. This astronomical alignment served both religious and practical functions, the latter by providing reliable markers for construction layout.

- Leveling Techniques: Achieving a perfectly level foundation was critical for large structures. The Egyptians employed various methods to ensure a flat starting surface. One common technique involved creating a perimeter trench filled with water, allowing the surface level to be marked accurately. Another method involved pounding in stakes and leveling them using a water level or a plumb bob attached to a set square. This meticulous leveling often extended across vast areas, a formidable task given the primitive tools available.

Material Science and Selection

The selection and understanding of materials were fundamental to the longevity of Egyptian structures. The engineers possessed an intimate knowledge of geological resources and the properties of different stone types.

- Limestone: The primary building material for most pyramids and temples was local limestone, quarried from sites such as Toura. This relatively soft, workable stone was ideal for the large-scale stacking required for monumental construction. Its abundance made it an economical choice.

- Granite: For sarcophagi, lining chambers, and obelisks, harder stones like granite (from Aswan) and basalt were preferred. These materials offered greater durability and aesthetic appeal but presented significant challenges in quarrying, transportation, and shaping due to their intrinsic hardness.

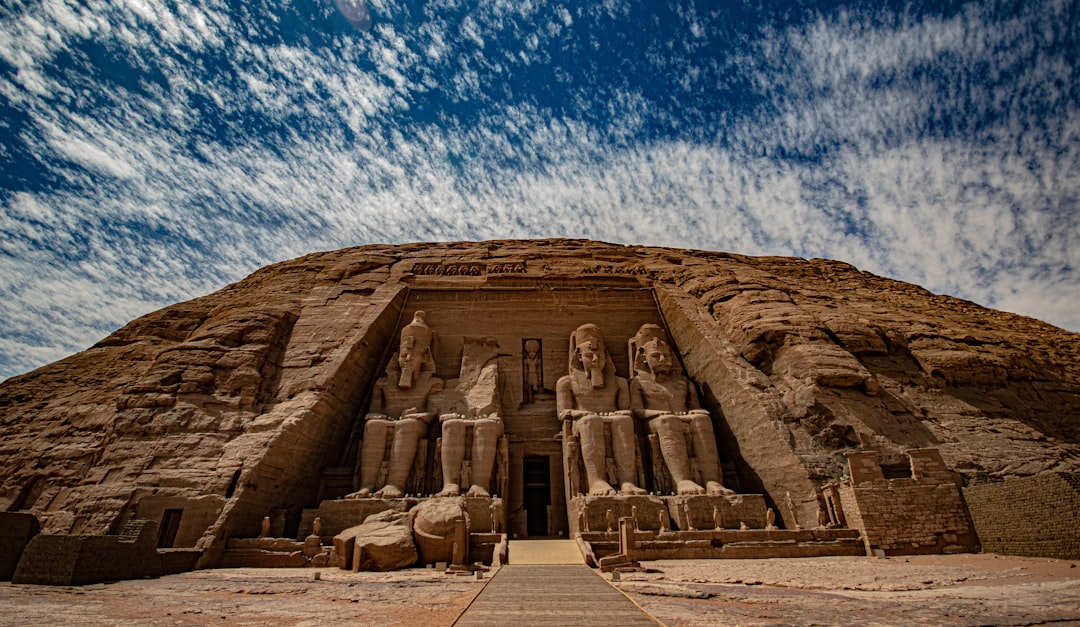

- Sandstone: Later new kingdom temples frequently incorporated sandstone, often sourced from Gebel el Silsila. This material offered a balance between workability and structural integrity, allowing for intricate carvings and a different architectural aesthetic compared to earlier limestone structures.

- Mortar and Grout: While often cited as master stonemasons, the Egyptians also utilized mortar. Early mortars were often a simple mixture of gypsum and sand, acting more as a lubricant for moving stones and a filler for irregularities rather than a strong adhesive. For more refined work, plaster was employed, and in some instances, red ochre was added for coloration or protective properties.

Ancient Egypt is renowned for its remarkable engineering feats, from the construction of the pyramids to the intricate irrigation systems that supported agriculture along the Nile. A fascinating article that delves deeper into the advanced engineering techniques employed by the ancient Egyptians can be found at this link: Advanced Engineering in Ancient Egypt. This resource explores the innovative methods and tools used by ancient builders, shedding light on how they achieved such monumental structures that continue to captivate the world today.

Quarrying and Transportation: The Logistics of Mass

The scale of ancient Egyptian construction projects necessitated highly organized and labor-intensive quarrying and transportation operations. The sheer volume of stone, often weighing many tons per block, required innovative solutions for extraction and movement across significant distances.

Quarrying Methods

The extraction of stone from bedrock was a multi-stage process involving specialized tools and techniques. The methods varied based on the type of stone being quarried.

- Soft Stone (Limestone, Sandstone): For softer stones, copper chisels, stone hammers, and wooden wedges were used. Chisels were employed to cut channels around the desired block. Wooden wedges, driven into crevices and then soaked with water, would expand and split the rock along natural fault lines or engineered weaknesses. This method allowed for the extraction of relatively uniform blocks with minimal waste.

- Hard Stone (Granite, Basalt): Quarrying hard stones was far more challenging. Dolerite pounding stones were used to batter the rock, gradually breaking it down. Evidence from uncompleted obelisks at Aswan clearly shows the marks left by such tools. Heating and quenching methods, whereby the stone was heated and then rapidly cooled with water, were also potentially used to induce thermal stress and cause fractures, though direct archaeological evidence for widespread practice is scarce.

- Finishing and Initial Shaping: Once extracted, blocks were often given a rudimentary shape at the quarry site. This preliminary shaping reduced the overall weight, making transportation more efficient, and minimized the amount of material that needed to be worked at the construction site. Quarry marks and identification codes were sometimes painted or incised onto blocks to aid in their placement.

Transportation Systems

Moving millions of tons of stone, some blocks weighing in excess of 1,000 tons (e.g., the Colossi of Memnon), was a monumental logistical feat. The Nile River played a central role in this process.

- River Transport: The Nile served as the primary artery for transporting heavy materials. Large barges and rafts, propelled by sails and oars, were used to move blocks from distant quarries like Aswan (granite) to construction sites in the north. The annual inundation of the Nile, which raised water levels significantly, would have facilitated the movement of heavily laden barges into canals and closer to construction sites.

- Land Transport: Once offloaded from barges, blocks needed to be moved across land to the construction site. Sledges, often made of wood, were employed for this purpose. Lubrication of the ground (possibly with water or oil) and the placement of rolling logs beneath the sledges are believed to have reduced friction, making the pulling of heavy loads by numerous laborers more manageable. Depictions on tomb walls, such as that of Djehutihotep, show large statues being pulled by teams of men, with water being poured on the ground in front of the sledge.

- Ramps and Lever Systems: For lifting and positioning blocks, a combination of ramps and lever systems was crucial. The debate over the design of pyramid ramps continues, with theories ranging from straight, linear ramps to spiraling ramps encircling the structure. Regardless of their specific configuration, ramps provided the grade necessary for pulling blocks upwards. Levers, fulcrums, and counterweights would have been essential for fine-tuning the placement of individual blocks, though detailed evidence of their specific application is limited.

Construction Techniques: Pillars of Ingenuity

The actual assembly of these massive structures required not only brute force but also sophisticated understanding of mechanics and structural stability. The methods employed demonstrate a practical application of physics.

Lifting and Positioning Blocks

The placement of multi-ton blocks with remarkable precision, particularly at height, remains one of the most enigmatic aspects of Egyptian engineering.

- Ramp Systems: As mentioned, ramps were the primary method for raising blocks. Their gradient would have been carefully engineered to allow human and animal power to pull the stone. The sheer volume of material needed to build these ramps was substantial, often exceeding the volume of the monument itself, presenting an additional logistical challenge.

- Leverage and Wedging: Once a block reached its intended height, levers and wedges would have been used to precisely maneuver it into its final position. Small gaps between blocks, often less than 1 millimeter, indicate a masterly control over placement. This precision was crucial for structural stability, as it distributed weight evenly and reduced stress concentrations.

- Scaffolding and Temporary Structures: While monumental stone scaffolding as we understand it today is not evident, temporary earth and rubble ramps might have served similar functions, providing working platforms for artisans and engineers as the structure rose. The meticulous carving and finishing of surfaces at various heights suggest the existence of accessible workstations.

Structural Integrity and Stability

The longevity of Egyptian structures is a testament to their inherent stability, a result of careful design and construction.

- Interlocking Masonry: The precise fitting of blocks, often without significant mortar, created an interlocking system that distributed loads efficiently. The slight inward slope (batter) seen in many temple walls also contributed to their stability, countering outward thrust.

- Corbelled Vaults and Arches: While true keystone arches were not widely adopted for monumental structures until later periods, the Egyptians did employ corbelled arches and vaults, particularly for relieving chambers above internal passages in pyramids or for roofing small spaces. This technique involved progressively stepping courses of stone inward until they met at the apex, distributing the weight outwards rather than relying on a central keystone.

- Weight Distribution and Foundations: The massive foundations of pyramids and temples were designed to distribute the immense weight of the superstructure over a wide area, preventing subsidence. In some cases, bedrock was leveled and prepared, while in others, deep trenches filled with rubble provided a stable base. The use of relieving chambers above burial chambers in the Great Pyramid is a classic example of load management, diverting the immense weight of the masonry above away from the delicate chambers below.

Tools and Workforce: The Hands of the Craftsmen

The execution of these grand projects was intrinsically linked to the tools available and the organization of the vast workforce required.

Simple but Effective Tools

The tools employed by the Ancient Egyptians were relatively simple by modern standards but were applied with remarkable skill and effectiveness.

- Copper and Bronze Tools: Early tools were primarily made of copper, later transitioning to bronze as metallurgy advanced. Chisels, saws, drills, and hammers were commonplace. While copper and bronze are relatively soft, constant resharpening and the sheer force applied by a large workforce compensated for their material limitations.

- Stone Tools: For working harder stones, or for initial roughening of softer stones, diorite or dolerite mallets and pounders were invaluable. These harder stones, used as percussive tools, could effectively break down surfaces. Quartzite was also used for grinding and polishing.

- Measuring and Marking Instruments: Plumb bobs and lines were used for vertical alignment. Set squares and cubit rules ensured accurate angles and measurements. Stretched ropes, often made from flax, were utilized for laying out distances and defining perimeters, perhaps even forming rudimentary compasses for drawing large curves.

- Leverage Tools: Wooden levers, possibly reinforced with copper or bronze caps, were essential for manipulating heavy stones once they were in position. Rollers, while not definitively proven for all contexts, would have facilitated horizontal movement.

Organization of Labor

The scale of Egyptian construction projects necessitated a highly organized and managed workforce, often numbering in the tens of thousands.

- Skilled Artisans and Laborers: The workforce was stratified, comprising highly skilled architects, sculptors, and stone masons, alongside a large contingent of unskilled laborers. The skilled artisans would have been responsible for the intricate carvings, finishing, and precise placement, while the laborers performed the strenuous tasks of quarrying, transporting, and lifting.

- Seasonal Labor and State Organization: A significant portion of the labor force was likely drawn from agricultural workers during the annual Nile inundation, when farming was impossible. This provided a large, readily available pool of manpower. The state organization, through a sophisticated bureaucracy, managed food distribution, accommodation, and the logistics of sustaining such a large workforce for extended periods. This dispels the myth of widespread slave labor in the construction of the pyramids, instead suggesting a system of paid, although likely coerced, labor.

- Discipline and Management: To coordinate thousands of workers, a hierarchical management structure was in place. Foremen and overseers directed teams, ensuring tasks were completed efficiently and safely. Rations, medical care, and housing were provided, as evidenced by archaeological finds at workers’ villages near Giza.

Advanced engineering in ancient Egypt is a fascinating topic that reveals the remarkable ingenuity of the civilization. The construction of the pyramids, for example, showcases their sophisticated understanding of mathematics and physics. For those interested in exploring this subject further, a related article can be found at Real Lore and Order, which delves into the techniques and tools used by ancient Egyptians to achieve such monumental feats. This resource provides valuable insights into how their engineering prowess laid the groundwork for future architectural advancements.

Enduring Legacy: Lessons from the Sands

| Aspect | Details | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Pyramid Construction |

|

Demonstrates advanced knowledge of geometry, surveying, and logistics |

| Material Engineering |

|

Enabled large-scale construction and durable monuments |

| Water Management |

|

Supported agriculture and urban development in arid environment |

| Architectural Design |

|

Reflected religious beliefs and enhanced structural stability |

| Metrology |

|

Ensured consistency and precision in engineering projects |

The architectural and engineering marvels of ancient Egypt are more than just impressive ruins; they are a timeless testament to human perseverance, ingenuity, and a civilization’s capacity for organized achievement.

Impact on Later Civilizations

The techniques and architectural styles developed in Egypt demonstrably influenced subsequent civilizations, particularly the Greeks and Romans.

- Architectural Motifs: Egyptian columns, obelisks, and monumental sculpture were admired and copied. The Doric order, for instance, bears a stylistic resemblance to some early Egyptian column types.

- Engineering Principles: While direct transmission of every specific technique is hard to trace, the fundamental principles of quarrying, large-scale transportation, and efficient deployment of labor would have been observed and adapted by those who encountered Egyptian structures. The Romans, in particular, were known for their engineering prowess and undoubtedly drew inspiration from their predecessors’ monumental feats, even importing Egyptian obelisks for their own public spaces.

Continuous Fascination and Research

The allure of ancient Egyptian engineering continues to captivate modern minds. Ongoing archaeological research, coupled with advancements in reverse engineering and computer modeling, constantly refines our understanding.

- Unanswered Questions: Despite centuries of study, many questions remain. The exact ramp systems used for the Great Pyramid, the precise methods for shaping the extremely hard granite sarcophagi, and the finer details of tool use continue to be subjects of active debate and investigation.

- Modern Relevance: The problem-solving methodologies employed by the Egyptians, their ability to organize vast resources, and their commitment to long-term projects offer valuable lessons in project management and large-scale engineering even today. Their structures stand not merely as ancient relics but as enduring metaphors for aspirational human endeavor, challenging us to consider what can be achieved with determination, ingenuity, and a collective vision.

Therefore, dear reader, when you contemplate the pyramids or the temples along the Nile, see not only the wonders of ancient art but also the profound engineering behind their permanence. Observe the precise cuts, the massive stones, and the enduring forms, and recognize them as blueprints from a past civilization that mastered not just monumental building, but also the very art of creation itself.

STOP: Why They Erased 50 Impossible Inventions From Your Textbooks

FAQs

What are some examples of advanced engineering in ancient Egypt?

Ancient Egypt showcased advanced engineering through the construction of the pyramids, such as the Great Pyramid of Giza, complex irrigation systems, massive temples, and sophisticated stone-cutting techniques.

How did ancient Egyptians transport large stones for their constructions?

They used sledges pulled by workers, often lubricated the sand with water to reduce friction, and employed ramps and rollers to move massive stones to construction sites.

What materials did ancient Egyptian engineers primarily use?

They mainly used limestone, sandstone, granite, and mudbrick for their structures, along with copper and bronze tools for carving and construction.

How did ancient Egyptian engineering contribute to agriculture?

They developed intricate irrigation systems, including canals, basins, and shadufs (hand-operated devices) to control the Nile’s flooding and distribute water efficiently to farmlands.

What role did mathematics and astronomy play in ancient Egyptian engineering?

Mathematics and astronomy were crucial for precise measurements, aligning structures with celestial bodies, and planning construction projects, ensuring accuracy and durability in their engineering feats.