Quantum measurement presents fundamental challenges that differ significantly from classical measurement scenarios. In conventional quantum measurements, the act of observation necessarily disturbs the quantum system, causing wavefunction collapse and yielding definitive results. Weak measurements represent an alternative measurement protocol that extracts limited information from quantum systems while minimizing disturbance to their quantum states.

This measurement technique enables researchers to probe quantum phenomena that remain inaccessible through standard projective measurements. Weak measurements preserve quantum coherence to a greater degree than strong measurements, allowing for the investigation of quantum trajectories and the extraction of information about quantum states between preparation and final measurement. Beyond theoretical interest, weak measurements demonstrate practical applications across multiple scientific disciplines.

The technique allows for information extraction without substantial state modification, providing enhanced capabilities for studying quantum system dynamics and behavior. The methodology encompasses specific measurement protocols, underlying quantum mechanical principles, and diverse applications within quantum physics research, contributing to expanded understanding of quantum mechanical phenomena and measurement theory.

Key Takeaways

- Weak measurements provide a method to probe quantum systems with minimal disturbance, revealing subtle quantum properties.

- The concept of weak values offers new insights into quantum states, often yielding results outside traditional eigenvalue ranges.

- Applications of weak measurements span quantum entanglement studies, precision metrology, and quantum information processing.

- Experimental techniques for weak measurements require careful control to balance measurement strength and system disturbance.

- Despite challenges, weak measurements contribute to foundational debates and hold promise for advancing quantum technologies.

The Concept of Weak Values in Quantum Physics

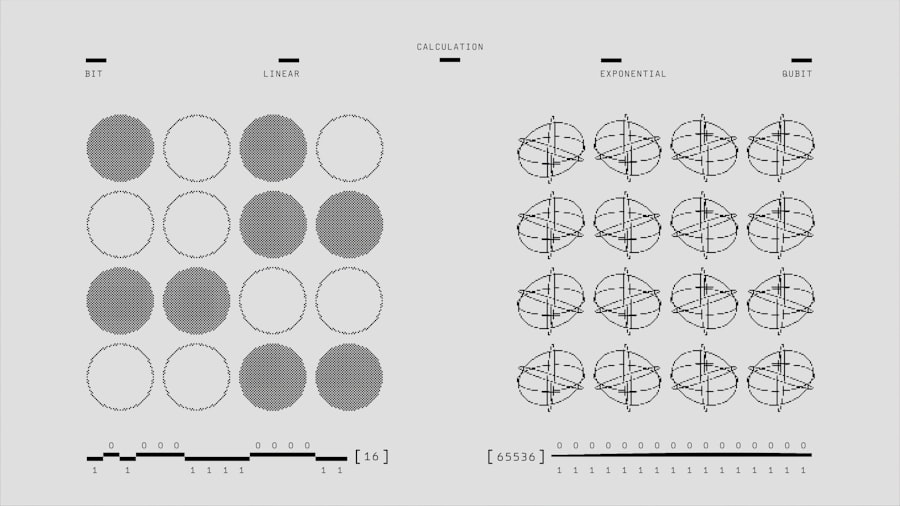

At the heart of weak measurements lies the concept of weak values, a term that may initially seem paradoxical. In essence, a weak value is an expectation value that can be obtained from a weak measurement process. Unlike traditional expectation values, which are determined through strong measurements that collapse the wave function, weak values can exist outside the conventional range of outcomes.

This means that when you perform a weak measurement on a quantum system, you may obtain results that are not confined to the eigenvalues of the observable being measured. The implications of weak values are profound. They allow you to probe the quantum state in a way that reveals information about the system without forcing it into a definitive state.

This unique characteristic enables you to explore phenomena such as quantum superposition and entanglement in ways that were previously unattainable. As you engage with the concept of weak values, you will find that they challenge your understanding of measurement and reality itself, prompting you to reconsider what it means to observe a quantum system.

Understanding the Weak Measurement Process

To grasp the weak measurement process, it is essential to understand how it differs from traditional measurement techniques. In a typical strong measurement, you interact with a quantum system in such a way that its wave function collapses into one of its eigenstates, providing you with a definite outcome. In contrast, weak measurements involve a gentle interaction with the system, allowing it to remain in a superposition of states.

This subtle approach enables you to extract partial information about the system while preserving its overall coherence. During a weak measurement, you typically couple the quantum system to a measuring device in a way that minimizes disturbance. The interaction is designed to be weak enough that it does not significantly alter the state of the system.

As you perform this measurement, you collect data over many trials, averaging the results to obtain meaningful information about the weak value associated with the observable. This process highlights the delicate balance between gaining knowledge and preserving the integrity of the quantum state, illustrating the unique nature of weak measurements.

Applications of Weak Measurements in Quantum Physics

Weak measurements have found applications across various domains within quantum physics, providing valuable insights into complex phenomena. One notable application is in the study of quantum trajectories, where weak measurements allow you to track the evolution of a quantum system over time without collapsing its wave function. This capability enables you to observe how quantum states evolve and interact, offering a deeper understanding of processes such as decoherence and quantum state manipulation.

Another significant application lies in the realm of quantum optics. Weak measurements can be employed to investigate light-matter interactions at unprecedented levels of precision. By measuring properties such as phase shifts or polarization states with minimal disturbance, you can explore fundamental questions about light’s behavior and its interaction with matter.

These insights not only advance your understanding of quantum optics but also pave the way for innovations in technologies like quantum communication and cryptography.

Weak Measurements and Quantum Entanglement

| Metric | Description | Typical Values | Relevance in Weak Measurements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weak Value | Expectation value obtained from weak measurement, can be complex or outside eigenvalue spectrum | Varies; can exceed eigenvalue range, e.g., -10 to +10 for spin-1/2 systems | Central quantity revealing quantum paradoxes and contextuality |

| Measurement Strength (g) | Coupling constant between system and measuring device | Typically << 1 (e.g., 0.01 to 0.1) | Determines how “weak” the measurement is; smaller values minimize disturbance |

| Post-selection Probability | Probability of successfully selecting a particular final state after measurement | Ranges from near 0 to 1, often low (e.g., 0.01 to 0.1) | Impacts signal-to-noise ratio and measurement efficiency |

| Pointer Shift | Change in measuring device’s pointer variable due to weak measurement | Proportional to measurement strength and weak value; typically small | Used to infer weak values indirectly |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | Ratio of pointer shift to measurement noise | Varies; often low in single trials, improved by averaging | Determines precision and reliability of weak measurement outcomes |

| Disturbance to System | Degree to which the measurement perturbs the quantum state | Minimal for weak measurements; quantified by fidelity loss or state change | Allows extraction of information with minimal collapse |

Quantum entanglement is one of the most intriguing phenomena in quantum mechanics, where particles become interconnected in such a way that the state of one particle instantaneously influences the state of another, regardless of distance. Weak measurements play a crucial role in studying entangled systems by allowing you to probe their properties without disrupting their delicate correlations. This capability enables you to explore entanglement’s nuances and gain insights into its fundamental nature.

By employing weak measurements on entangled particles, you can investigate how entanglement persists under various conditions and how it can be manipulated for practical applications. For instance, weak measurements can help elucidate the behavior of entangled states in quantum computing or enhance protocols for secure communication. As you delve into this intersection between weak measurements and entanglement, you’ll uncover new dimensions of understanding that challenge classical intuitions about separability and locality.

Experimental Techniques for Weak Measurements

The implementation of weak measurements requires sophisticated experimental techniques designed to minimize disturbance while maximizing information extraction. One common approach involves using an ancillary system—a separate measuring device—that interacts with the quantum system in a controlled manner. This ancillary system allows you to perform weak measurements by coupling it gently to the target system, ensuring that any disturbance remains negligible.

Another technique involves utilizing post-selection, where you measure an observable after performing a weak measurement on a different observable. By carefully selecting which outcomes to retain based on specific criteria, you can enhance your ability to extract meaningful information about the weak value associated with the observable of interest. These experimental strategies highlight the ingenuity required to navigate the complexities of weak measurements while maintaining fidelity to the underlying quantum principles.

Challenges and Limitations of Weak Measurements

Despite their promise, weak measurements are not without challenges and limitations. One significant hurdle is achieving sufficient precision in your measurements while maintaining minimal disturbance to the quantum system. The delicate balance between these two factors can be difficult to strike, particularly when dealing with systems that exhibit rapid dynamics or are highly sensitive to external influences.

Additionally, interpreting weak values can be non-trivial. Since they can take on values outside the expected range of eigenvalues, understanding their physical significance requires careful consideration. You may find yourself grappling with questions about what these values represent and how they relate to traditional concepts in quantum mechanics.

As researchers continue to explore these challenges, they will refine techniques and develop new frameworks for interpreting weak measurements within the broader context of quantum theory.

Weak Measurements and the Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics

The advent of weak measurements has sparked renewed discussions about the interpretation of quantum mechanics itself. Traditional interpretations often grapple with issues related to measurement and observation, leading to debates about realism and determinism in quantum systems. Weak measurements challenge these interpretations by providing a framework for understanding how information can be extracted without collapsing wave functions or imposing definitive outcomes.

As you engage with these philosophical implications, you’ll find that weak measurements encourage a more nuanced view of reality in quantum mechanics. They suggest that observation does not necessarily equate to definitive knowledge but rather represents an interaction that can yield partial insights into complex systems. This perspective invites you to reconsider your assumptions about measurement and reality while exploring how weak measurements fit into various interpretations of quantum mechanics.

The Role of Weak Measurements in Quantum Information Processing

In recent years, weak measurements have emerged as valuable tools in quantum information processing—a field dedicated to harnessing quantum phenomena for computational and communicative purposes.

Moreover, weak measurements can enhance protocols for secure communication by allowing for more robust encoding and decoding strategies that leverage entangled states.

As you explore this intersection between weak measurements and quantum information processing, you’ll uncover innovative approaches that could revolutionize how we approach computation and communication in an increasingly quantum world.

Future Directions in Weak Measurements Research

The field of weak measurements is still evolving, with numerous avenues for future research waiting to be explored. One promising direction involves refining experimental techniques to achieve even greater precision while minimizing disturbance further. Advances in technology may enable you to probe increasingly complex systems and extract valuable insights from them.

Additionally, researchers are investigating potential applications beyond traditional quantum physics contexts—such as biology or materials science—where weak measurements could provide new perspectives on intricate processes at microscopic scales. As this field continues to grow, it will undoubtedly yield exciting discoveries that deepen your understanding of both fundamental physics and practical applications.

Conclusion and Implications of Weak Measurements in Quantum Physics

In conclusion, weak measurements represent a groundbreaking approach to understanding quantum systems by allowing you to extract information with minimal disturbance. Their unique characteristics challenge traditional notions of measurement and reality while offering profound insights into complex phenomena such as entanglement and superposition. As you reflect on their implications for both theoretical interpretations and practical applications within quantum physics, it becomes clear that weak measurements hold significant promise for advancing our understanding of the quantum world.

As research continues to unfold in this area, you will likely witness further developments that enhance our grasp of fundamental principles while paving the way for innovative technologies rooted in quantum mechanics.

Weak measurements in quantum mechanics offer a fascinating approach to extracting information about quantum systems without significantly disturbing them. For a deeper understanding of this concept, you can explore the article on weak measurements available at this link. This article delves into the principles and implications of weak measurements, providing insights into how they challenge traditional notions of measurement in quantum theory.

FAQs

What are weak measurements in quantum mechanics?

Weak measurements are a type of quantum measurement that only slightly disturbs the quantum system, allowing partial information to be obtained without causing the wavefunction to collapse completely. This contrasts with strong (or projective) measurements, which fully collapse the quantum state.

How do weak measurements differ from strong measurements?

Strong measurements provide definite outcomes and collapse the quantum state into an eigenstate of the measured observable. Weak measurements, on the other hand, extract limited information with minimal disturbance, resulting in a “weak value” that can sometimes lie outside the range of eigenvalues.

What is the significance of weak values?

Weak values are the results obtained from weak measurements and can provide insights into quantum systems that are not accessible through traditional measurements. They can reveal subtle quantum effects and have applications in quantum foundations and precision metrology.

Can weak measurements be used to observe quantum systems without collapsing their state?

Yes, weak measurements allow partial observation of a quantum system with minimal disturbance, enabling the study of quantum phenomena without fully collapsing the wavefunction. However, the information gained is limited and often requires statistical analysis over many trials.

What are some practical applications of weak measurements?

Weak measurements have been used in quantum state tomography, precision measurement enhancement, quantum error correction, and exploring fundamental questions in quantum mechanics such as the nature of quantum trajectories and paradoxes.

Are weak measurements widely accepted in the physics community?

While weak measurements are a well-established theoretical and experimental tool, their interpretation and implications continue to be topics of active research and debate within the quantum physics community.

How are weak measurements implemented experimentally?

Weak measurements are typically implemented by coupling the quantum system weakly to a measuring device or probe, such that the interaction is gentle enough to avoid full collapse but still imparts measurable information about the system’s state.

Do weak measurements violate the uncertainty principle?

No, weak measurements do not violate the uncertainty principle. They provide limited information about a quantum system without fully collapsing the state, but the uncertainty principle still governs the precision and disturbance trade-offs inherent in quantum measurements.