Navigating the swells of the Pacific Ocean using traditional Polynesian wayfinding techniques represents a remarkable feat of human ingenuity and environmental understanding. This ancient art, passed down through generations, allowed Polynesian voyagers to traverse vast distances across seemingly featureless expanses of water, connecting islands that are often thousands of miles apart. At its core, this mastery lies in the ability to read the subtle language of the ocean, a language spoken not just in the movement of waves, but also in the whispers of the wind and the stories told by the stars.

In recent decades, there has been a significant revival and academic interest in these practices. Modern researchers and practitioners are working to document, understand, and perpetuate these invaluable skills, recognizing their potential to enrich our understanding of human history and our relationship with the natural world. This article will delve into the fundamental principles of Polynesian wayfinding, with a particular focus on the use of “swell maps”—a conceptual navigation tool derived from understanding ocean wave patterns—and the crucial role of the canoe itself, often constructed from wood, in these oceanic journeys.

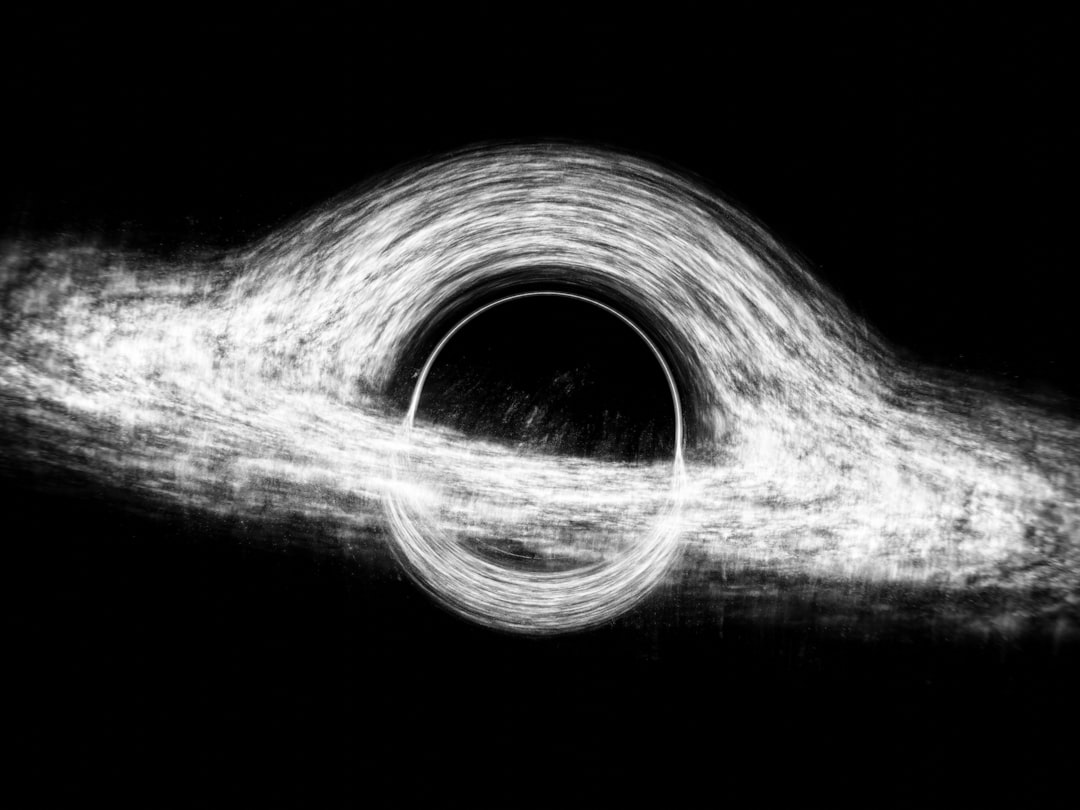

The ocean, to the untrained eye, might appear as a chaotic and unpredictable force. However, for skilled Polynesian navigators, the swells were akin to a living document, a constantly updating map of the world. They didn’t just see waves; they perceived them as directional messages, carrying information about distant landmasses, prevailing winds, and the very geography of the ocean floor.

The Genesis of Swells: Wind as the Sculptor

Swells are fundamentally born from wind. The friction between the moving air and the surface of the water transfers energy, creating ripples that can grow into larger undulations. The intensity, duration, and fetch (the distance over which the wind blows unimpeded) of the wind all contribute to the size and character of the resulting swell. Navigators understood that different wind patterns produced different types of swells, and by observing these characteristics, they could deduce the wind’s origin and its likely direction.

Persistence and Directionality of Swells

A key concept is that once a swell is generated, it can travel vast distances across the ocean, far from the winds that created it. This persistence is what makes swells such reliable navigation aids. A swell generated by a storm thousands of miles away can still reach a navigator and provide clues to the storm’s origin. Furthermore, the directionality of a swell is a primary indicator of its source. Navigators learned to identify dominant swell directions and how they interacted with each other.

Swell Interaction and Interference: The Ocean’s Crosstalk

The ocean is a dynamic environment where multiple swells, generated by different wind events in various locations, converge and interact. This intersection creates intricate patterns of constructive and destructive interference. Navigators possessed an acute sensitivity to these interactions. They could “read” the resulting wave patterns, differentiating between swells that were traveling in the same general direction and those that were originating from different quadrants of the horizon. This complex interplay of waves was not a source of confusion but a rich tapestry of information. For them, the ocean was a grand conversation, and they were fluent listeners.

Recognizing Different Swell Families

Polynesian navigators did not simply see a jumble of waves. They could distinguish different “families” of swells based on their period (the time between successive crests), amplitude (height), and angular spread. A navigator would learn to identify the consistent hum of a large, long-period swell born from a distant storm, distinguishing it from the shorter, choppier waves generated by local winds. The absence of one type of swell or the dominance of another could signal a change in weather patterns or the proximity of land.

The Concept of “Swell Maps”: Navigating by Wave Patterns

The term “swell map” is a modern interpretation of an ancient conceptual tool. Polynesians did not draw literal maps on paper. Instead, they developed a sophisticated mental cartography, visualizing the ocean not as a flat expanse but as a three-dimensional space where swells moved like currents on a river. This mental map was informed by a deep understanding of swell behavior and its relationship to geography.

Dead Reckoning and Swell Cues

While celestial navigation and observation of natural phenomena were paramount, swells acted as a continuous form of dead reckoning. Even when clouds obscured the stars, or during periods of calm, the underlying swell patterns persisted. Navigators would use their knowledge of established swell directions between islands and note any deviations or interactions to maintain their course. If the expected swell from a known direction was absent, or if an unexpected swell appeared, it signaled a potential deviation from the intended path or the presence of something disruptive.

Reaching and Running Swells: Essential Knowledge

Understanding how to sail with the swells (running) or at an angle to them (reaching) was fundamental to efficiency and safety. The way a canoe interacted with a swell determined its speed and stability. Navigators knew that a canoe could be driven much faster and more safely when harnessing the energy of the swells. Conversely, sailing directly into large, powerful swells could be dangerous, risking capsizing. Thus, the ability to interpret and utilize swell direction was directly tied to the physical handling of the vessel.

Polynesian wayfinding is a remarkable navigation technique that relies on the natural elements of the ocean, including swell patterns, to guide voyagers across vast distances. An insightful article that delves into this ancient practice and its connection to swell maps and the use of wood in constructing traditional canoes can be found at this link. This resource provides a deeper understanding of how Polynesian navigators utilized their environment to traverse the Pacific, showcasing the intricate knowledge and skills passed down through generations.

The Wood Beneath: The Role of the Canoe in Wayfinding

The canoe, typically constructed from wood, was not merely a vessel for transport; it was an integral partner in the wayfinding process. Its design, materials, and how it interacted with the ocean were all crucial elements that enabled long-distance voyaging. The navigator and the canoe were a symbiotic unit, working in concert to confront the immensity of the Pacific.

Wood as a Sustainable Resource: Respect for the Forest

The selection of appropriate wood was a critical first step. Different types of wood, such as whetū,matai, and kauri, were chosen for their strength, buoyancy, and workability. The process of selecting and felling trees was often imbued with cultural and spiritual significance, reflecting a deep respect for the natural world and a belief in the interconnectedness of all things. This wasn’t just about harvesting a resource; it was about understanding the spirit of the tree and its potential to serve as a vessel.

Hull Design and Stability: Riding the Waves

The hull design of the Polynesian canoe was optimized for open ocean conditions. Outriggers, for example, provided crucial stability, preventing the canoe from capsizing in rough seas. The shape of the hull was meticulously crafted to minimize drag and to allow the canoe to efficiently ride the swells. A well-designed hull could harness the energy of the waves, propelling the vessel forward with remarkable speed and grace. It was like a surfer’s board, designed to meet the wave and use its power.

The Canoe as a Sensory Tool: Feeling the Ocean

Navigators often sailed with their feet bare and their hands on the canoe. This allowed them to feel the subtle vibrations and movements of the hull, which in turn provided them with direct feedback about the ocean’s behavior. Changes in the canoe’s pitch and roll could indicate shifts in swell direction, the presence of currents, or even the approach of another vessel. The wood of the canoe acted as an extension of the navigator’s senses, transmitting the ocean’s subtle communications.

Material Properties and Performance: Wood’s Resilience

The inherent properties of different woods were exploited to create durable and responsive vessels. Some woods were known for their buoyancy, others for their resistance to rot and marine borers. The joinery techniques used to construct double-hulled canoes or to attach outriggers were also critical, ensuring the structural integrity of the vessel over extended voyages. The choice of wood and its treatment were as important as the skill of the builder.

The Horizon’s Many Voices: Reading the Signs

While swell maps were a primary navigational tool, they were always used in conjunction with a vast array of other observations. The horizon, the sky, the sea, and the life within it all contributed to the navigator’s comprehensive understanding of their position and the journey ahead.

Celestial Navigation: The Stars as Guiding Lights

The stars were the most reliable and consistent navigational aids. Navigators memorized the rising and setting points of key stars on the horizon and their apparent movement across the night sky. These celestial bodies provided fixed reference points, allowing navigators to maintain a consistent bearing over long distances. They were the unwavering compass in the sky.

Zenith Stars and Their Significance

Certain stars that pass directly overhead (zenith stars) held particular importance. A navigator could track their zenith passage to determine their latitude. By knowing the specific stars that passed overhead at different latitudes, they could pinpoint their position with remarkable accuracy. Each zenith star was like a waypoint in the sky, marking a specific band of latitude.

Cloud Formations and Atmospheric Indicators: The Sky’s Mood

The appearance of clouds, their type, and their movement could provide valuable information about wind patterns and the proximity of land. For example, specific types of clouds might form over islands due to rising moist air. Navigators also paid attention to the color of the sky, the presence of rainbows, and other atmospheric phenomena that could indicate approaching weather systems. The sky was a canvas, and the clouds were its transient brushstrokes, telling stories of the weather.

The “Mirage Effect” and Island Recognition

Navigators could sometimes detect the presence of land even before it was visible on the horizon through a phenomenon often referred to as the “mirage effect.” The refraction of sunlight through the moist air above land can create an illusion of elevation or a shimmering appearance. Skilled observers learned to recognize these subtle visual cues.

Marine Life and Bird Migrations: Nature’s Guides

The presence of specific marine animals and the flight patterns of seabirds were also crucial indicators. Certain fish species congregated in particular areas, and the migratory routes of birds often mirrored established travel paths between islands. Observing a flock of birds heading in a consistent direction was a strong signal of land in that direction. The ocean was teeming with life, and each creature was a potential signpost.

Bird Behavior as Navigation Cues

Seabirds, in particular, are highly attuned to the presence of land. They typically feed offshore and return to land to rest and nest. A navigator observing birds flying in a consistent direction, especially in the morning or evening, could infer the direction of nearby land. The angle and urgency of their flight provided further clues.

The Art of the Voyage: Practical Application of Wayfinding

Mastering Polynesian wayfinding was not an academic pursuit but a highly practical skill honed through years of experience and apprenticeship. The ability to integrate all these observational elements into a coherent navigational strategy was the hallmark of a true navigator.

The Nainoa Thompson School of Thought: Modern Revival

The revival of Polynesian wayfinding in recent decades owes much to figures like Nainoa Thompson, who has spearheaded voyages like the Hōkūleʻa. These voyages have not only demonstrated the efficacy of traditional methods but have also inspired a new generation of navigators and a deeper appreciation for this ancient knowledge system. The modern revival is about re-learning and re-applying the wisdom of our ancestors.

Mentorship and Apprenticeship: Passing the Torch

Wayfinding was, and still is, primarily taught through mentorship and apprenticeship. Novice navigators would spend years at sea, observing, assisting, and gradually taking on more responsibility under the guidance of experienced masters. This hands-on learning process was essential for developing the intuitive understanding and deep knowledge required. The wisdom was not found in books but in the salty air and the experienced hands of a mentor.

The Canoe as a Navigator’s Home: Psychological and Practical Aspects

For extended voyages, the canoe was more than just a mode of transport; it was a home. Navigators had to manage the physical demands of sailing, the psychological challenges of isolation, and the constant responsibility for the lives of the crew. The intimate connection between the navigator and their vessel fostered a profound sense of trust and reliance. The canoe was a floating island of sorts, a sanctuary in the vast ocean.

Provisions and Seafaring Sustenance

The planning and management of provisions were critical for long voyages. Knowledge of edible plants, sustainable fishing techniques, and effective food preservation methods were essential. The success of a voyage depended not only on navigation but also on the ability to sustain the crew throughout the journey. A well-supplied canoe was a testament to foresight and resourcefulness.

The Social and Cultural Significance of Voyaging

Beyond the practicalities of navigation, Polynesian voyaging held immense cultural and social significance. These voyages facilitated trade, the exchange of knowledge and culture, and the expansion of Polynesian societies across the Pacific. The ability to undertake such journeys was a source of prestige and a testament to the skill and bravery of the voyagers. The canoes were the arteries of a vast oceanic civilization.

Inter-Island Relations and Cultural Exchange

The ability to travel between islands fostered strong inter-island relationships and the sharing of cultural practices, languages, and traditions. This exchange enriched the diverse tapestry of Polynesian cultures and contributed to a shared sense of identity across a vast geographical area. The canoes were not just carrying people and goods, but also the very essence of their cultures.

Polynesian wayfinding is a remarkable navigation technique that relies on the natural elements of the ocean, including swell patterns, to guide voyagers across vast distances. An insightful article that delves deeper into this ancient practice and its connection to swell maps made from wood can be found here. This resource explores how skilled navigators interpret the ocean’s movements and utilize their knowledge of the stars and winds, showcasing the incredible ingenuity of Polynesian culture.

The Legacy of Wayfinding: Relevance in the Modern World

| Metric | Description | Value/Details |

|---|---|---|

| Material | Primary material used for traditional swell maps | Wood (typically coconut or breadfruit wood) |

| Map Dimensions | Typical size of a Polynesian swell map | Approximately 1.5 to 2 meters in length |

| Wave Pattern Representation | Number of wave ridges carved to represent swell directions | 5 to 7 ridges per map |

| Navigation Range | Distance range these maps help navigate by swell patterns | Up to 100 nautical miles |

| Accuracy | Estimated accuracy of swell direction interpretation | Within 10 degrees of actual swell direction |

| Usage Period | Historical period when these maps were predominantly used | Pre-18th century to early 20th century |

| Crafting Time | Average time to carve a traditional swell map | 2 to 4 weeks |

| Preservation | Typical lifespan of wooden swell maps under proper care | 50+ years |

The legacy of Polynesian wayfinding extends far beyond its historical context. Its principles offer valuable insights into ecological understanding, risk assessment, and the harmonious relationship between humanity and the natural world—lessons that are arguably more relevant today than ever before.

Ecological Literacy and Environmental Stewardship

The profound understanding of natural systems that underpins traditional wayfinding provides a compelling model for ecological literacy. Navigators were deeply attuned to the interconnectedness of the ocean, atmosphere, and biosphere. Their practices underscore the importance of observing and respecting the environment, rather than seeking to dominate it. This is a blueprint for living in balance with our planet.

Sustainable Resource Management and Traditional Ecological Knowledge

The sustainable use of resources, from selecting timber for canoes to managing food supplies, highlights the wisdom embedded in traditional ecological knowledge. This knowledge, passed down through generations, offers valuable lessons for contemporary approaches to resource management and conservation. The ancestral wisdom holds keys to a more sustainable future.

The Power of Intuition and Observation: A Counterpoint to Technology

In an era increasingly dominated by technological navigation, the principles of wayfinding remind us of the power of intuition, keen observation, and deep environmental awareness. While modern technology is invaluable, the human capacity for sensing and interpreting the natural world remains a vital skill. The navigator’s innate connection to their environment serves as a reminder of what can be lost when we rely solely on machines.

Reconnecting with Nature Through Traditional Skills

The resurgence of interest in traditional skills like wayfinding offers an opportunity for individuals to reconnect with nature on a deeper level. Engaging with these practices can foster a greater appreciation for the natural world and inspire a more mindful and sustainable way of living. It’s about more than just navigation; it’s about rediscovering our place within the grand tapestry of life.

Adapting Ancient Knowledge for Contemporary Challenges

The conceptual framework of “swell maps” and the holistic approach to navigation emphasize a sophisticated understanding of complex systems. These principles can be conceptually adapted to address contemporary challenges in fields ranging from data analysis to urban planning, demonstrating the enduring utility of time-tested, nature-derived wisdom. The ocean’s waves can inspire innovative solutions far beyond the sea.

The Future of Wayfinding: Education and Preservation

Ensuring the continued existence and transmission of Polynesian wayfinding knowledge is crucial. This involves supporting educational initiatives, documenting practices, and encouraging new generations to engage with and learn from this invaluable cultural heritage. The future of this ancient art lies in its continued practice and its thoughtful integration into modern life.

SHOCKING: 50 Artifacts That Prove History Was Erased

FAQs

What is Polynesian wayfinding?

Polynesian wayfinding is a traditional navigation method used by Polynesian voyagers to travel across the Pacific Ocean. It relies on natural cues such as stars, ocean swells, wind patterns, and bird flight paths rather than modern instruments.

How do swell maps assist in Polynesian wayfinding?

Swell maps help navigators understand the direction and behavior of ocean swells, which are consistent wave patterns generated by distant winds. By interpreting these swells, wayfinders can determine their position and maintain their course even when stars are not visible.

What role does wood play in Polynesian wayfinding?

Wood is essential in Polynesian wayfinding as it is traditionally used to construct the canoes and navigation tools. Skilled woodworkers craft the hulls, paddles, and sometimes carved instruments that aid in reading environmental signs during voyages.

Are modern Polynesian navigators still using traditional wayfinding techniques?

Yes, many modern Polynesian navigators continue to practice and teach traditional wayfinding techniques, including the use of swell maps and natural indicators, to preserve their cultural heritage and maintain a connection to ancestral knowledge.

Can anyone learn Polynesian wayfinding methods?

While Polynesian wayfinding requires extensive training and experience, many cultural organizations and navigation schools offer courses to teach these traditional skills to interested learners, emphasizing hands-on practice and mentorship from experienced navigators.