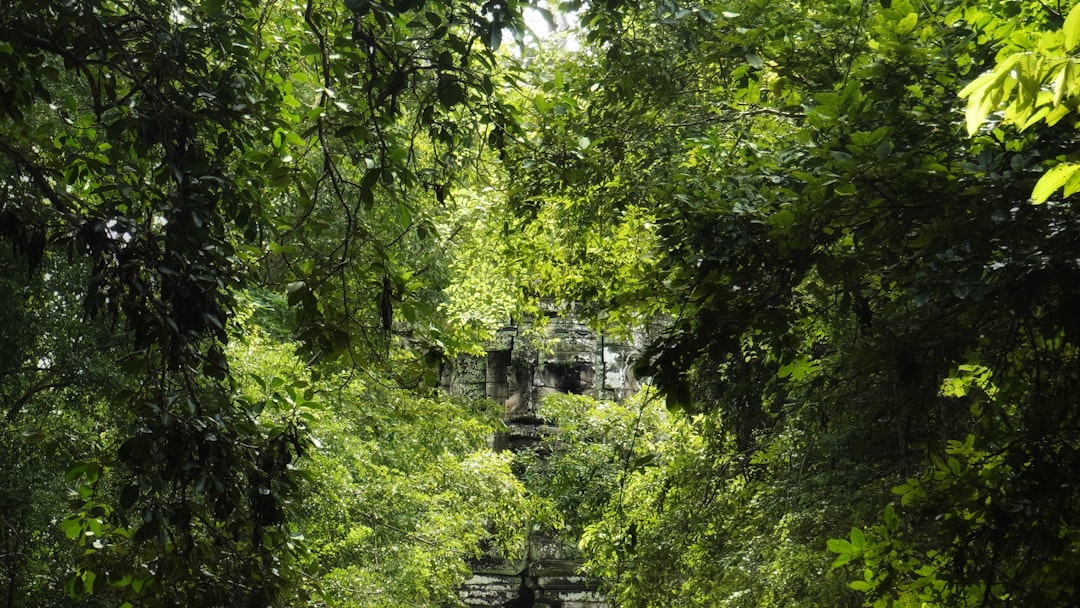

The whispers of lost civilizations, buried beneath the dust of millennia, carry lessons for a world teetering on the precipice of environmental change. These societies, once vibrant hubs of human ingenuity, ultimately succumbed to the ravages of ecological mismanagement. Yet, within their ruins lie forgotten blueprints for resilience, strategies that allowed them to endure and even thrive for extended periods in the face of profound environmental shifts. By examining their triumphs and their failures, one can glean invaluable insights into the art of surviving ecological collapse, a skill becoming increasingly critical in the 21st century.

The dawn of civilization, marked by the development of agriculture and settled societies, was intrinsically linked to humanity’s increasing ability to manipulate its environment. This newfound mastery, however, often sowed the seeds of future distress. Early agriculturalists, eager to cultivate fertile lands, frequently engaged in practices that, while providing short-term gains, destabilized delicate ecosystems. The pursuit of surplus, a cornerstone of societal development, often came at a considerable ecological cost.

Deforestation: The Ax Bites Deep

- The Genesis of Abundance and its Shadow: The transition from nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyles to settled agriculture necessitated the clearing of vast tracts of forest. Forests provided not only timber for construction and fuel but also space for cultivation. This initial stage of forest clearance, while seemingly manageable, set a precedent for a deeply ingrained human tendency to view natural resources as inexhaustible stores. The story of early deforestation is a cautionary tale: where trees once stood, fertile soil began to erode, carrying away the very lifeblood of the agricultural enterprise.

- Consequences of Canopy Removal: The removal of forest cover had a cascade of detrimental effects. It led to soil erosion, reducing agricultural productivity and silting up waterways. Changes in local microclimates, often leading to reduced rainfall and increased temperatures, further stressed already vulnerable agricultural systems. The loss of biodiversity, both plant and animal, also diminished the resilience of the surrounding environment, making it less capable of absorbing shocks.

- Case Studies in Tree Loss: The Mediterranean region, where many early civilizations flourished, provides stark examples. The widespread deforestation around ancient Rome, for instance, fueled its expansion but eventually contributed to agricultural decline and land degradation. Similarly, the depletion of timber resources in the ancient Near East may have played a role in the decline of certain city-states, forcing populations to seek new, less degraded lands.

Water Management: A Double-Edged Sword

- Harnessing the Lifeline: Water has always been the lifeblood of civilizations. Early societies developed sophisticated irrigation systems, canals, and reservoirs to channel water for agriculture and domestic use. These feats of engineering allowed for the cultivation of arid lands, supporting larger populations and fostering urban development. The ingenuity behind these water management systems is undeniable, representing a significant step in human technological advancement.

- The Perils of Arid Lands: However, concentrating water resources, especially in arid and semi-arid regions, created new vulnerabilities. Over-irrigation could lead to salinization, rendering fertile land infertile over time. Dependence on these engineered systems meant that any disruption, whether due to drought, conflict, or system failure, could have catastrophic consequences for the population.

- Salinization as a Silent Killer: The Mesopotamian civilizations, often cited as cradles of human civilization, experienced severe salinization of their agricultural lands due to intensive irrigation with high-salinity river water. This gradual degradation of the soil is believed to have significantly contributed to their eventual decline, a slow poisoning of the land that sustained them. The once-fertile crescent began to shrink.

Population Growth and Resource Strain

- The Multiplier Effect: The ability to produce surplus food through intensive agriculture enabled unprecedented population growth. This demographic boom, while a sign of societal success, placed increasing pressure on available resources. The demand for land, water, timber, and other raw materials escalated, pushing societies to extract more and more from their environment.

- The Subsistence Threshold: As populations grew, societies approached or even surpassed the carrying capacity of their local environments. The margin of error for agricultural failure, whether due to natural disaster or mismanagement, narrowed considerably. A single bad harvest could tip a community from surplus to scarcity, triggering widespread hardship.

- Shifting Landscapes: The cumulative impact of these pressures – deforestation, erosion, salinization, and resource depletion – fundamentally altered landscapes. What were once verdant plains could become barren steppes, and once-reliable water sources could dwindle. The environment, in essence, began to push back, a silent protest against unsustainable practices.

In exploring the resilience of lost civilizations in the face of environmental collapse, a fascinating article can be found at Real Lore and Order. This piece delves into various historical examples, illustrating how societies adapted to changing climates and resource scarcity. By examining the strategies employed by these civilizations, we gain valuable insights into the potential for modern societies to navigate similar challenges today.

The Wisdom of Adaptation: Societies That Endured

Despite the inherent challenges, certain civilizations demonstrated remarkable adaptability, developing strategies to navigate environmental stresses and maintain their viability for prolonged periods. These societies understood that resilience was not solely about resource acquisition but also about ecological harmony and efficient resource utilization. Their successes offer a glimpse into what is possible when humanity works with nature, rather than against it.

Sustainable Agriculture: Working With the Land

- Diversification as a Shield: Unlike monoculture systems that are vulnerable to disease and specific environmental conditions, many successful ancient societies practiced diversified agriculture. They cultivated a variety of crops, often including drought-resistant and nutrient-fixing species, which provided a buffer against crop failure and helped maintain soil fertility. This agricultural tapestry was far more robust than a single thread.

- Terracing and Contour Farming: In hilly or mountainous regions, civilizations developed sophisticated terracing and contour farming techniques. These methods prevented soil erosion by creating level planting surfaces and slowing down water runoff. The Incan civilization, for example, masterfully utilized terracing in the Andes, creating arable land on impossibly steep slopes.

- Agroforestry and Integrated Systems: Some societies integrated trees into their agricultural landscapes, a practice known as agroforestry. This approach provided a sustainable source of timber and fuel, improved soil fertility through leaf litter, and created microclimates that benefited crops. These systems mimicked natural ecosystems, creating a symbiotic relationship between agriculture and forest cover.

- Conservation of Water Sources: Beyond large-scale irrigation, many communities developed localized water conservation strategies. These included the construction of small check dams, infiltration galleries, and careful management of local springs and wells, ensuring a more distributed and secure water supply.

Resource Management: The Art of Frugality

- Circular Economies and Waste Reduction: The concept of a circular economy, where resources are reused and recycled, was implicit in the practices of many ancient societies. Building materials were often salvaged and repurposed. Organic waste was composted and returned to the land, closing the nutrient loop. This was not a matter of ideology but of necessity; waste was a luxury they could not afford.

- Polyculture and Companion Planting: Beyond crop diversity, complementary planting strategies were employed. Certain plants, when grown together, could deter pests, attract beneficial insects, or improve soil nutrient availability. This natural pest control reduced reliance on external inputs and maintained a healthier ecosystem.

- Water Harvesting and Retention: Communities in drier regions developed ingenious methods for collecting and storing rainwater. Cisterns, reservoirs, and even strategically placed depressions in the landscape helped capture precious precipitation, minimizing reliance on ephemeral rivers or groundwater.

- Sustainable Forestry Practices: While deforestation was a problem, some societies also practiced forms of sustainable forest management. Selective harvesting, coppicing (allowing trees to regrow from stumps), and the cultivation of specialized timber species ensured a continuous supply of wood without complete depletion.

Social Organization and Resilience

- Decentralized Systems and Local Autonomy: Societies with more decentralized political structures and a degree of local autonomy often proved more resilient. When a central authority failed, or a localized disaster struck, these communities were better equipped to adapt and survive through local knowledge and cooperative efforts.

- Community-Based Resource Allocation: Systems of communal land ownership or cooperative resource management fostered a sense of shared responsibility and ensured that resources were distributed equitably, preventing the hoarding that could exacerbate scarcity. This collective stewardship was a powerful social lubricant in times of stress.

- Knowledge Transmission and Innovation: Effective mechanisms for transmitting ecological knowledge across generations were crucial. This included oral traditions, apprenticeships, and the development of early forms of writing that recorded agricultural techniques, weather patterns, and resource management strategies. Innovation was often rooted in deeply ingrained traditions.

The Cataclysmic Collapse: When the Balance Tips

Even societies with sophisticated adaptation strategies were not immune to disaster. When environmental stressors intensified beyond the capacity of their adaptive measures, the delicate balance tipped, leading to societal collapse. Understanding the mechanisms of these collapses is as vital as understanding the resilience that preceded them. The fall of a civilization is not a sudden event but a slow unraveling, a frayed rope finally snapping.

Environmental Thresholds and Tipping Points

- The Erosion of Carrying Capacity: When the demands placed upon an ecosystem, whether by population growth, intensive agriculture, or resource extraction, consistently exceeded its capacity to regenerate, a point of irreversible decline was reached. The land, like a debt-ridden ledger, could no longer balance its accounts.

- Feedback Loops and Amplification: Environmental degradation often triggers positive feedback loops, where a change leads to a further change in the same direction, amplifying the problem. For example, deforestation leads to erosion, which reduces soil fertility, which necessitates clearing more land, further exacerbating deforestation.

- The Role of Climate Change: While not always catastrophic in the ancient world, significant climatic shifts, such as prolonged droughts or increased periods of intense rainfall, could overwhelm even well-adapted societies, pushing them past their breaking point. The straws that break the camel’s back are often weather-related.

Social and Political Fragmentation

- Resource Scarcity and Conflict: As resources dwindled, competition intensified, both within and between communities. This often led to internal strife, civil unrest, and warfare, further destabilizing society and hindering cooperative efforts to address environmental challenges. The fight for dwindling resources can turn neighbors into enemies.

- Erosion of Trust and Authority: When leaders or governing bodies failed to adequately address the growing environmental crises or provide for their populations, trust eroded. This could lead to the breakdown of social order, the collapse of institutions, and a descent into anarchy or fragmentation into smaller, less viable units.

- Migration and Displacement: Faced with uninhabitable conditions, large-scale migrations and displacements of populations often occurred. These movements could strain the resources of receiving areas, create new conflicts, and lead to the dispersal and loss of established societal structures. The wanderlust of desperate people can be a destructive force.

The Interplay of Factors: A Multifaceted Demise

- No Single Smoking Gun: It is crucial to understand that societal collapse is rarely attributable to a single cause. Rather, it is typically the result of a complex interplay of environmental, social, economic, and political factors. A forest fire might start the conflagration, but dry tinder and strong winds ensure its rapid spread.

- Vulnerability and External Shocks: Even resilient societies could be pushed over the edge by unexpected external shocks, such as prolonged droughts, volcanic eruptions, or the introduction of new diseases, which interacted with existing environmental vulnerabilities to produce catastrophic outcomes.

- The Weight of History: The cumulative impact of centuries of resource depletion and environmental degradation, even if seemingly minor in the short term, could eventually create a critical mass of fragility, making a society susceptible to collapse when faced with even moderate challenges.

Lessons from the Dust: What Ancient Resilience Teaches Us

The study of lost civilizations is not an academic exercise in cataloging ancient ruins; it is a vital exploration of human ingenuity and folly. The strategies employed by societies that thrived, even for centuries, in challenging environments offer a prescient guide for our current predicament. The echoes of their successes – and their failures – resonate with urgent relevance.

The Preeminence of Ecological Awareness

- Understanding Interconnectedness: The most successful ancient societies possessed an intuitive, often deeply ingrained, understanding of the interconnectedness of their environment. They recognized that the health of their crops was linked to the health of their soil, the availability of water, and the presence of beneficial insects. This holistic perspective is a stark contrast to the reductionist approaches that often characterize modern resource management.

- Long-Term Thinking Over Short-Term Gain: The emphasis on long-term sustainability, rather than immediate gratification, was a hallmark of enduring civilizations. They understood that present choices would have consequences for future generations. This temporal perspective is a virtue desperately needed in our era of rapid technological advancement and short political cycles.

- The Value of Local Knowledge: Traditional ecological knowledge, passed down through generations, was a repository of wisdom about local ecosystems and how to live within their limits. This knowledge, often dismissed as primitive, was in fact a sophisticated system of information tailored to specific environments.

The Power of Adaptive Governance and Social Structure

- Decentralization and Local Empowerment: The success of decentralized governance structures in fostering resilience is a significant takeaway. Empowering local communities with the autonomy to manage their resources and respond to local challenges allows for more agile and context-specific solutions. A thousand small boats are often more maneuverable in a storm than one massive ship.

- Cooperation and Shared Responsibility: The importance of social cohesion, cooperation, and a sense of shared responsibility in overcoming adversity cannot be overstated. Societies that fostered strong community ties and equitable resource distribution were better equipped to weather environmental storms.

- The Role of Education and Knowledge Transfer: Effective mechanisms for transmitting knowledge, both practical and ecological, across generations are fundamental to long-term survival. Societies that valued learning and adaptability were more likely to innovate and overcome new challenges.

Embracing Frugality and Circularity

- The Efficiency of Waste Not: The ancient world, out of necessity, was a master of frugality. The absence of mass production and disposability meant that resources were cherished, reused, and repurposed. This implicit circular economy stands in stark contrast to our linear “take-make-dispose” model.

- Sustainable Consumption Patterns: Surviving civilizations did not aspire to infinite growth or endless consumption. Their material needs were met within ecological limits, and their understanding of wealth was often divorced from material accumulation.

- The Need for a Paradigm Shift: To truly learn from these lost societies, humanity must embrace a fundamental shift in its values and priorities. This involves moving away from an anthropocentric view of nature towards a more ecocentric one, recognizing our interdependence with the natural world, and prioritizing long-term ecological health over short-term economic gain.

In exploring the resilience of ancient societies, a fascinating article discusses how lost civilizations managed to endure environmental collapse through innovative adaptations and resource management. These strategies not only ensured their survival but also provide valuable lessons for contemporary societies facing similar challenges. For a deeper understanding of these remarkable survival tactics, you can read more in this insightful piece on the topic at this link.

The Future’s Scaffolding: Building on Ancient Foundations

| Lost Civilization | Environmental Collapse Factor | Survival Strategy | Outcome | Key Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mesopotamia (Sumerians) | Salinization of soil | Shifted agriculture to less saline areas, irrigation management | Temporary recovery, eventual decline | Crop yield reduced by 30% over 200 years |

| Ancient Maya | Severe drought | Water storage systems, terracing, crop diversification | Partial survival in some regions, collapse in others | Reservoir capacity increased by 40% |

| Easter Island (Rapa Nui) | Deforestation and soil erosion | Resource rationing, shift to marine resources | Population decline, cultural transformation | Fish consumption increased by 50% |

| Indus Valley Civilization | River course changes and flooding | Relocation of settlements, flood-resistant architecture | Gradual migration and decline | Settlement relocation within 50 km radius |

| Ancient Egypt | Variable Nile flooding | Construction of canals and reservoirs | Long-term agricultural stability | Nile flood control improved by 25% |

The collapse of civilizations is a recurring motif in human history, a somber testament to our capacity for self-destruction when we sever our ties with the natural world. However, within the ruins of these fallen societies lie blueprints for survival, forgotten wisdom waiting to be rediscovered. The question is not whether we face environmental collapse, but how we will choose to respond. The choices made by our ancestors, etched in the dust of ages, offer us a stark choice: repeat their mistakes, or learn from their resilience.

The Imperative of Proactive Adaptation

- Beyond Mitigation: Embracing Adaptation: While efforts to mitigate climate change are crucial, they are insufficient on their own. Humanity must proactively embrace adaptation strategies informed by the lessons of the past. This means investing in sustainable land management, water conservation, and resilient infrastructure, not as a luxury, but as an existential necessity.

- Investing in Ecological Restoration: As many lost civilizations ultimately succumbed to degraded environments, a focus on ecological restoration is paramount. Reforestation, soil rebuilding, and the protection of biodiversity are not merely environmental initiatives; they are foundational elements of long-term human survival.

- Building Social and Economic Resilience: Ecological resilience is inextricably linked to social and economic resilience. Strengthening community bonds, fostering equitable resource distribution, and developing adaptable economic systems are essential components of a robust response to environmental challenges.

The Recalibration of Human Values

- Redefining Progress: The current definition of progress, heavily reliant on perpetual economic growth and material consumption, is fundamentally incompatible with ecological sustainability. A recalibration of what constitutes a successful society is urgently needed, one that values ecological health, social well-being, and intergenerational equity as much as, if not more than, economic metrics.

- Cultivating Ecological Literacy: A widespread understanding of ecological principles and our interconnectedness with the natural world is essential. This requires integrating ecological education into curricula at all levels and fostering a culture that reveres and respects the natural systems that sustain us.

- The Ethics of Stewardship: Ultimately, surviving ecological collapse hinges on a profound ethical shift. Humanity must move from a position of dominion over nature to one of stewardship, recognizing our responsibility to protect and regenerate the planet for all living beings, present and future.

Charting a Course for the Future

- The Global Imperative: The environmental challenges we face are global in scope and require unprecedented international cooperation. The lessons from collapsed civilizations highlight the dangers of division and the necessity of collective action.

- Learning from Both Success and Failure: The study of lost civilizations provides a vital historical laboratory. By dissecting both their periods of thriving and their eventual downfall, we gain invaluable insights into the complex dynamics of human-environment interactions. The ghosts of the past are not merely specters; they are teachers offering their final, crucial lessons.

- The Choice is Ours: The environmental challenges of the 21st century are formidable, but not insurmountable. The wisdom of lost civilizations, if heeded, can provide the scaffolding for a more sustainable and resilient future. The path forward requires humility, foresight, and a willingness to learn from the triumphs and tragedies of those who came before. The echoes from the dust are a clarion call; our response will determine if we are to become another whisper in the winds of time.

STOP: Why They Erased 50 Impossible Inventions From Your Textbooks

FAQs

What are some examples of lost civilizations that survived environmental collapse?

Some lost civilizations that managed to survive environmental collapse include the Maya, who adapted to drought conditions, and the Ancestral Puebloans, who adjusted their agricultural practices in response to changing climates.

What strategies did these civilizations use to adapt to environmental changes?

These civilizations employed various strategies such as developing advanced irrigation systems, diversifying crops, relocating settlements, and implementing resource management practices to cope with environmental stress.

How did environmental collapse impact the social structures of these civilizations?

Environmental collapse often led to social upheaval, including shifts in political power, changes in trade networks, and sometimes the decentralization of authority as communities adapted to new challenges.

Can studying lost civilizations help us address modern environmental issues?

Yes, understanding how past civilizations responded to environmental collapse provides valuable insights into resilience, sustainable resource management, and adaptation strategies relevant to current global challenges.

What role did technology play in the survival of these civilizations?

Technology such as water conservation techniques, soil management, and architectural innovations played a crucial role in enabling these civilizations to mitigate the effects of environmental collapse and sustain their populations.