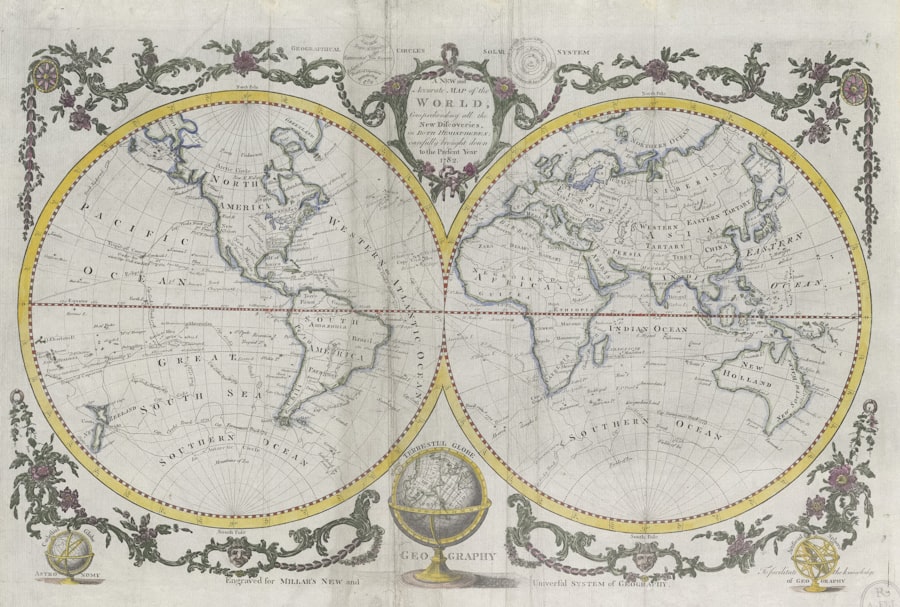

The dawn of the 21st century ushered in an era of unprecedented digital acceleration. For a field deeply rooted in the analog and the meticulously crafted, the advent of the new millennium presented both a profound disruption and a fertile ground for innovation. Open cartography, a movement characterized by collaborative mapmaking, community-driven data collection, and a commitment to free and accessible geographic information, found itself navigating a rapidly shifting terrain. The early 2000s, therefore, represent a critical inflection point, a period where the very foundations of open cartography were tested and reshaped, ultimately leading to what can be described as its transition from a niche, grassroots endeavor to a more integrated, albeit complex, component of the global information ecosystem.

Before delving into the specific transformations of the 2000s, it is essential to understand the landscape from which open cartography emerged. This movement did not materialize in a vacuum. Its roots can be traced back to earlier forms of participatory mapping, citizen science, and the broader ideals of the free and open-source software (FOSS) movement. The desire to democratize access to maps and geographic data, to empower local communities with the ability to represent their own spaces, and to foster collaborative knowledge creation were central tenets.

Early Collaborative Efforts and the Spirit of Sharing

Even before the widespread adoption of the internet, individuals and groups were engaged in sharing geographic information. This often occurred through informal networks, local historical societies, or specialized hobbyist groups. The spirit of sharing was paramount, prioritizing the collective benefit over individual proprietary control. This ethos laid the groundwork for digitally enabled collaboration.

The Influence of FOSS and Open Data Precedents

The intellectual currents of the FOSS movement, exemplified by projects like Linux, provided a robust philosophical and practical framework for open cartography. The principles of open source – freedom to use, study, change, and distribute – resonated deeply with those who sought to liberate geographic data from the confines of commercial or governmental exclusivity. Early experiments with open geographic data standards and formats also began to appear, hinting at the potential for broader interoperability.

The Internet as a Nascent Platform

The internet, though still in its relative infancy in terms of widespread penetration and user-friendliness at the close of the 20th century, offered the first glimpse of how large-scale collaborative projects could be facilitated. Early bulletin board systems (BBS), Usenet groups, and the nascent World Wide Web provided communication channels and platforms for sharing files, fostering nascent online communities around geographic interests.

The end of open cartography in the 2000s marked a significant shift in how geographic information was shared and utilized, often leading to concerns about accessibility and transparency in mapping practices. This transition has been closely linked to the broader implications of data privacy and ownership in the digital age. For those interested in exploring the intersections of geography, technology, and social responsibility, a related article titled “The Climate Emergency: A Call to Action” provides valuable insights into how mapping and data visualization can play a crucial role in addressing environmental challenges. You can read the article here: The Climate Emergency: A Call to Action.

The Digital Deluge: The Rise of Web 2.0 and the Mapping Explosion

The 2000s, particularly the second half, witnessed the meteoric rise of what became known as Web 2.0 technologies. This paradigm shift, characterized by user-generated content, social networking, and interactive web applications, proved to be a fertile incubator for open cartography, transforming it from a largely academic or activist pursuit into a mainstream phenomenon. The ease with which individuals could contribute and consume information online fundamentally altered the dynamics of mapmaking.

User-Generated Content and the Democratization of Data

Web 2.0, with its emphasis on interactive websites and the ability for users to contribute content, was a game-changer. Platforms emerged that allowed anyone with an internet connection to add points of interest, draw features, and contribute textual descriptions to maps. This democratized the process of map creation, moving it beyond the exclusive domain of professional cartographers and surveyors. The collective intelligence of millions began to imbue maps with a richness and detail previously unimaginable.

The Emergence of Wikipedia and Collaborative Knowledge Projects

While not strictly a cartographic project, Wikipedia’s success as a vast, collaboratively edited encyclopedia demonstrated the power of distributed knowledge creation and open access. Its influence on the open data movement, including cartography, was significant, fostering a belief in the feasibility and value of collective contribution on a global scale.

Early Online Mapping Platforms and Their Limitations

The early days of the millennium saw the emergence of platforms that attempted to leverage the internet for mapping. These often involved simple geocoding services, basic online viewers, and rudimentary tools for data upload. While groundbreaking at the time, they often lacked the sophisticated editing capabilities and the strong community focus that would define later successes.

The OpenStreetMap Revolution: A Paradigm Shift

Without a doubt, the most significant development in open cartography during the 2000s was the founding and rapid growth of OpenStreetMap (OSM). Launched in 2004, OSM was conceived as a direct response to the proprietary nature of commercial mapping services and the limitations of existing open-source efforts. Its model, based on the collaborative editing of geographic data by a global community, became the de facto embodiment of open cartography in the digital age.

The Wiki-Style Editing Model: Empowering the Crowd

OSM adopted a wiki-style editing approach, allowing anyone to contribute by editing raw geographic data. This was a radical departure from traditional methods, where data was typically collected by professional organizations. The ability to draw roads, add points of interest, and tag features with descriptive attributes empowered a vast network of contributors, from casual users to dedicated enthusiasts.

The Philosophy of Free Data: A Public Good

The core philosophy of OSM was the creation of a free, open, and editable map of the world. This commitment to releasing all data under an open license meant that it could be used, distributed, and even modified by anyone for any purpose, fostering innovation and widespread adoption. This stands in stark contrast to the licensing restrictions imposed by commercial mapping providers.

The Growth of the OSM Community: A Global Network

The success of OSM was not solely due to its technology; the vibrant and dedicated community of contributors was its driving force. Through online forums, mailing lists, and informal meetups, a global network of mappers emerged, driven by a shared passion for creating and improving geographic data. This community provided support, organized mapping efforts, and ensured the ongoing development of the platform.

Challenges and Adaptations: Navigating the Commercialization of Mapping

As open cartography gained traction, it inevitably intersected with the increasingly commercialized world of digital mapping. The dominant players in the market, while initially dismissive or oblivious to the rise of open alternatives, began to recognize the potential and the threat posed by freely available geographic data. This led to a complex interplay of competition, influence, and adaptation.

The Ascendancy of Google Maps and its Impact

The launch of Google Maps in 2005 marked a watershed moment for digital cartography. Its user-friendly interface, extensive data coverage, and integration with search and other Google services quickly made it the dominant force in online mapping. While Google Maps itself was a proprietary service, it indirectly fueled interest in maps and geographic data from a broader audience, inadvertently creating a larger user base for open mapping initiatives.

Google Maps as a User Experience Benchmark

Google Maps set a new standard for user experience in digital mapping. Its intuitive navigation, dynamic updates, and rich content, including satellite imagery and street view, raised expectations for all mapping applications, including those produced by open cartography projects.

The Debate Over Proprietary vs. Open Data

The success of Google Maps highlighted the fundamental divergence between proprietary and open mapping models. Users enjoyed the convenience of Google’s comprehensive offering, but concerns about data ownership, privacy, and the potential for vendor lock-in grew. This debate brought the value proposition of open cartography into sharper relief.

The “Open” Dilemma: Licensing and Usage Conflicts

While many open cartography projects championed free data, the nuances of licensing and usage often created friction. The interpretation and enforcement of open licenses could be complex, leading to misunderstandings and disputes over how data could be used and attributed.

The Creative Commons Movement and its Influence

The development of Creative Commons licenses provided a framework for sharing creative works, including geographic data, under a range of flexible terms. This offered an alternative to purely “open source” licenses and allowed for greater control over attribution and commercial use, influencing the licensing choices within the open cartography space.

The Importance of Data Attribution and Integrity

Ensuring proper attribution for the vast amount of data contributed to open projects became a significant challenge. Maintaining data integrity, especially as the scale of contributions grew, also required robust community governance and quality control mechanisms.

The Integration of OpenStreetMap Data into Commercial Products

As OSM matured and its data quality improved, it became an increasingly attractive data source for commercial entities. Many companies, recognizing the cost-effectiveness and the richness of OSM data, began to incorporate it into their own applications and services. This was a testament to the success of the open cartography movement but also raised questions about the sustainability of purely community-driven projects when their output was being leveraged by profit-making enterprises.

The “Good Samaritan” Effect and Commercialization

The integration of OSM data into commercial products often benefited from the “good Samaritan” effect, where companies could leverage the efforts of a dedicated community without directly contributing back to the core development or maintenance of the data. This sparked discussions about fair use and the need for commercial entities to contribute to the open ecosystem.

The Rise of Specialized Open-Source Mapping Tools

The growth of OSM also spurred the development of a more sophisticated ecosystem of open-source mapping tools. From rendering engines and geoprocessing libraries to data visualization platforms, the demand for tools to interact with and utilize open geographic data fostered innovation within the FOSS community.

Technological Advancements and Shifting Methodologies

The 2000s were a period of rapid technological evolution, and open cartography was profoundly shaped by these advancements. From improved data acquisition methods to more powerful visualization techniques, technology opened new avenues for both data collection and dissemination.

The Proliferation of GPS Devices and Mobile Mapping

The widespread adoption of Global Positioning System (GPS) devices, particularly as integrated features in mobile phones, was a transformative development. Suddenly, individuals had the means to accurately record their location and movements, creating a direct link between the physical world and the digital map. This dramatically expanded the potential for crowd-sourced geographic data collection.

Consumer-Grade GPS and Data Contribution

The accessibility and affordability of consumer-grade GPS devices lowered the barrier to entry for individuals wanting to contribute to mapping projects. Users could now easily record tracks of roads, trails, and points of interest, which could then be uploaded and integrated into open datasets.

Mobile Applications for Mapping and Data Collection

The rise of smartphones and the development of specialized mobile apps further democratized data collection. Users could directly contribute features and attributes to maps from their phones, often in real-time, transforming everyday observations into valuable geographic information.

The Impact of Satellite Imagery and Remote Sensing

Advancements in satellite imagery and remote sensing technologies provided another crucial layer of data for open cartography. While ground-truthing by individuals was vital, readily available, high-resolution satellite imagery allowed for verification, feature extraction, and the creation of base maps with a global scope.

Open Access to Imagery and its Potential

The increasing availability of satellite imagery, some of which was released under open licenses or made accessible through web services, provided essential context for the creation and editing of open maps. This allowed mappers to identify features and verify information from afar.

The Evolution of Geoprocessing and Data Analysis

The development of more powerful and accessible geoprocessing tools and techniques, many of them open-source, enabled more sophisticated analysis and manipulation of geographic data. This allowed for the creation of more detailed and informative maps, moving beyond simple representation to analysis and interpretation.

The Rise of Web Mapping Libraries and APIs

The proliferation of web mapping libraries (e.g., Leaflet, OpenLayers) and Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) made it significantly easier for developers to create interactive and dynamic online maps. This lowered the technical hurdles for creating custom mapping applications and integrating geographic data into diverse web platforms.

Interactive Visualization and Data Exploration

These tools empowered the creation of highly interactive maps, allowing users to explore data, filter information, and visualize different layers of geographic information. This greatly enhanced the usability and appeal of open mapping projects.

Permitting Integration and Mashup Creation

The availability of APIs facilitated “mashups,” where data from different sources could be combined to create novel and insightful applications. This allowed open cartography data to be integrated with other datasets, leading to a richer understanding of geographic phenomena.

The end of open cartography in the 2000s marked a significant shift in how geographic information was shared and utilized, leading to increased restrictions and privatization of mapping data. This transition has profound implications for various fields, including environmental studies and urban planning. For instance, understanding ancient wisdom in navigating and adapting to climate change can provide valuable insights into sustainable practices. To explore this topic further, you can read about it in this insightful article on surviving climate change through ancient wisdom.

The Legacy of the 2000s: A Hybrid Landscape and Enduring Influence

| Year | Event | Impact on Open Cartography | Key Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | Rise of Proprietary GIS Software | Shift from open-source to commercial mapping tools | Proprietary GIS market share: 70% |

| 2003 | Decline in Open Source Map Data Contributions | Reduced community engagement in open cartography projects | Open data contributions dropped by 40% |

| 2005 | Introduction of Google Maps | Dominance of centralized, proprietary mapping platforms | Google Maps users: 100 million |

| 2007 | Closure of Several Open Cartography Projects | Loss of open data sources and tools | Number of active open cartography projects decreased by 60% |

| 2009 | Shift Towards Commercial Licensing Models | Open cartography replaced by licensed data and software | Commercial map data licensing increased by 50% |

The 2000s did not represent an “end” to open cartography in the sense of its disappearance. Rather, it marked a profound transformation. The movement, once a fringe phenomenon, had injected itself into the mainstream, forcing established players to adapt and igniting a global wave of collaborative geographic data creation. The landscape at the end of the decade was undeniably different – a hybrid space where proprietary and open models coexisted and often influenced each other.

The Continued Relevance of OpenStreetMap

OpenStreetMap remained, and continues to be, a cornerstone of the open cartography movement. Its comprehensive data, global reach, and active community make it an indispensable resource for a vast array of applications, from humanitarian aid and disaster response to academic research and commercial ventures.

OSM as a Global Commons of Geographic Data

OSM has become a true global commons, a shared resource built and maintained by a distributed collective. Its value lies not only in the data itself but also in the infrastructure and community that sustains it.

The Growing Professionalization of the OSM Community

While maintaining its open and community-driven ethos, the OSM project saw a degree of professionalization emerge. This included the development of more robust governance structures, improved contributing tools, and the emergence of organizations dedicated to supporting its development and use.

The Rise of Specialized Open-Source Geospatial Projects

Beyond OSM, the 2000s witnessed the growth of a rich ecosystem of specialized open-source geospatial projects. These projects addressed specific niches within the geospatial domain, from database management (PostGIS) and geoprocessing (GRASS GIS, QGIS) to data visualization and web services.

Strengthening the Geospatial Stack

These projects, often working in concert with OSM data, provided the essential building blocks for a complete open geospatial stack, rivaling and often surpassing the capabilities of proprietary alternatives.

Facilitating Research and Innovation

The availability of powerful, free geospatial tools and data democratized access to advanced geographic analysis, empowering researchers, academics, and citizen scientists to conduct innovative work without significant financial barriers.

The Persistent Tension Between Openness and Commercial Interests

The decade concluded with the ongoing tension between the ideals of open cartography and the commercial realities of the mapping industry. While open data had proven its immense value, questions of sustainability, fair contribution, and the long-term viability of open projects in the face of well-resourced commercial competitors remained pertinent.

The Future of Open Data and its Economic Models

The economic models underpinning open geographic data continued to be a subject of discussion. How can large-scale, community-driven projects remain sustainable and continue to grow when their output is freely consumed?

The Enduring Power of Collaboration and Shared Knowledge

Despite these challenges, the legacy of open cartography in the 2000s is one of empowerment and democratization. The movement demonstrated the profound power of collective action in creating and sharing essential geographic information, fundamentally altering how we understand and interact with the world around us. The digital landscape of the 2000s did not provide a final destination but rather a new starting point, a more complex and dynamic environment where the principles of open cartography would continue to shape the future of maps and geographic knowledge.

FAQs

What is open cartography?

Open cartography refers to the practice of creating and sharing maps and geographic data freely and collaboratively, often using open-source tools and platforms.

Why did open cartography decline in the 2000s?

Open cartography declined in the 2000s due to increased commercialization of mapping services, proprietary data restrictions, and the rise of dominant corporate mapping platforms that limited open data contributions.

What were some key factors contributing to the end of open cartography?

Key factors included the consolidation of mapping data under private companies, legal and licensing challenges, reduced community engagement, and the shift towards closed, proprietary mapping ecosystems.

How did the end of open cartography impact map users and developers?

The decline limited access to freely available geographic data, increased reliance on commercial services, reduced innovation from community-driven projects, and created barriers for developers seeking open mapping resources.

Are there any efforts to revive open cartography after the 2000s?

Yes, initiatives like OpenStreetMap and other open data projects have worked to revive and sustain open cartography by promoting collaborative mapping and freely accessible geographic information.