The history of optics is a vast and intricate tapestry, its threads woven through millennia of human ingenuity and observation. Among its earliest and most profound innovations are magnification lenses, simple yet transformative tools that unveiled hidden worlds and reshaped our understanding of the cosmos and the microscopic. This article delves into the fascinating journey of these ancient optical instruments, exploring their origins, their diverse applications across civilizations, and their eventual evolution into the sophisticated devices we know today.

The concept of magnification, the ability to make small objects appear larger, predates formal scientific inquiry. Observations of light bending through natural phenomena, such as water droplets or smooth, translucent stones, likely sparked the initial curiosity that would eventually lead to the deliberate creation of lenses.

Natural Phenomena as Precursors

Early humans no doubt observed the distorting and magnifying effects of water. A clear pool can make a pebble at its bottom appear closer and larger, a basic principle of refraction at play. Similarly, dew drops on leaves can act as miniature magnifiers, revealing the intricate venation of flora. These everyday occurrences, though not understood scientifically, would have subtly hinted at the potential of manipulating light for visual enhancement.

Anecdotal Evidence and Proto-Lenses

While concrete archaeological evidence for very early deliberate lenses remains scarce, anecdotal accounts and interpretations of artifacts offer tantalizing glimpses. Some researchers theorize that polished crystals or obsidian objects found in ancient digs, though primarily serving as jewelry or decorative items, might have been incidentally used for their magnifying properties. The focus, however, lies on more deliberate craftsmanship.

Ancient optics and the development of magnification lenses have fascinated scholars for centuries, shedding light on how early civilizations understood and manipulated light. A related article that delves into the historical advancements in optical technology can be found at Real Lore and Order. This resource explores the significance of lenses in ancient cultures and their impact on scientific progress, providing valuable insights into the evolution of optical instruments.

Mesopotamian, Egyptian, and Minoan Echoes

The earliest undisputed archaeological evidence for magnifying lenses emerges from civilizations with advanced craft traditions, particularly those proficient in carving and polishing materials.

The Nimrud Lens: A Contentious Artifact

One of the most famous and debated objects is the Nimrud lens, an oval-shaped piece of rock crystal unearthed in the ancient Assyrian city of Nimrud (present-day Iraq) and dating back to the 7th century BC. Measuring approximately 4.2 cm in diameter, this biconvex lens has a focal length of about 11 cm. While some scholars regard it as a mere decorative inlay, others argue forcefully for its use as a magnifying glass or a burning glass (a lens used to concentrate sunlight to start fires). Its optical quality, though not perfect by modern standards, is sufficient to demonstrate basic magnification. The debate surrounding its purpose highlights the difficulty in definitively determining intent from such ancient artifacts.

Egyptian and Minoan Refinements

Evidence from ancient Egypt also suggests proficiency in creating polished objects that could have served optical purposes. Spherical or hemispherical pieces of polished rock crystal, often found among burial goods, could have functioned as rudimentary magnifiers. Their inclusion in elite graves might indicate their value beyond mere aesthetic appeal, perhaps hinting at their practical applications for tasks requiring fine detail. Similarly, archaeological finds from Minoan Crete have yielded small, finely polished pieces of rock crystal, some of which exhibit measurable optical properties. The sophisticated craftsmanship of these civilizations, coupled with their interest in intricate designs and measurements, makes the development of early optical tools a plausible progression.

Classical Antiquity: Greek and Roman Contributions

The intellectual giants of ancient Greece and Rome, renowned for their philosophical inquiries and engineering prowess, also made contributions, both theoretical and practical, to the field of optics.

Theoretical Foundations in Greece

While direct evidence of Greeks producing sophisticated magnifying lenses is limited, their theoretical contributions laid essential groundwork. Euclid, in his Optics (c. 300 BC), discussed the principles of light reflection and perspective. Later, heroes like Ptolemy, in his own Optics (2nd century AD), compiled and expanded existing knowledge, formulating laws of refraction that, while not entirely accurate, marked a significant step in understanding how light bends when passing through different media. These intellectual frameworks, though not immediately leading to widespread lens production, cultivated an environment where optical phenomena were observed and analyzed.

Roman Practicality and “Burning Glasses”

The practical-minded Romans appear to have made more tangible progress in lens application. Pliny the Elder, a Roman author and natural philosopher, mentions in his Natural History (1st century AD) that physicians used “burning glasses” to cauterize wounds. These were convex lenses designed to concentrate sunlight to a focal point, generating enough heat to achieve cauterization. While their primary function was not magnification in the conventional sense, their existence demonstrates an understanding of the optical properties of lenses for practical application. Seneca, another Roman philosopher, also wrote about using a globe filled with water to magnify small letters, directly illustrating the use of a simple lens for magnification.

The Medieval Period: Bridges to the Renaissance

Following the decline of the Western Roman Empire, advancements in optics continued in various centers, particularly in the Islamic world, before being re-introduced to Europe during the High Middle Ages.

Islamic Scholars and the “Reading Stone”

The Islamic Golden Age witnessed a flourishing of scientific inquiry, including significant contributions to optics. Scholars like Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen, 10th-11th century), often regarded as the “father of modern optics,” conducted meticulous experiments and wrote extensively on the nature of light and vision. His monumental Book of Optics profoundly influenced Western European thought. While Alhazen did not invent the magnifying lens, his detailed explanations of concave and convex mirrors and spherical aberrations provided the theoretical underpinnings for their later development.

The “reading stone,” a plano-convex lens often made of quartz or beryl, likely emerged in parallel or shortly after Alhazen’s work. These hemispherical or segment-shaped lenses were placed directly on manuscripts to magnify text, greatly aiding individuals with presbyopia (age-related farsightedness) in reading. Evidence suggests their use in monasteries and scholarly centers across Europe, though their precise origin remains debated.

Early European Spectacles and the Vision Correction Revolution

The 13th century in Italy marked a critical turning point with the invention of spectacles. While the precise inventor is unclear, often attributed to Salvino D’Armate or Alessandro della Spina, the functional design of two convex lenses held in a frame rapidly spread across Europe. This innovation, though seemingly simple, had a profound impact. It significantly extended the active working lives of scribes, scholars, and artisans, allowing them to continue their detailed work even as their eyesight naturally declined. The widespread adoption of reading glasses laid the foundation for mass production of lenses and spurred further research into lens grinding and polishing techniques.

Ancient optics has always fascinated scholars, particularly in the context of magnification lenses used in early scientific endeavors. The development of these lenses not only advanced the field of astronomy but also played a crucial role in the evolution of various optical instruments. For a deeper understanding of this topic, you can explore a related article that delves into the historical significance and technological advancements of ancient optics by following this link. This resource provides valuable insights into how these early innovations laid the groundwork for modern optical science.

Beyond Reading: Diverse Applications of Ancient Lenses

| Period | Region | Optical Device | Material | Magnification Power | Notable Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circa 750 BCE | Assyria | Lens of Nimrud | Rock crystal | Approx. 3x | Possible magnification or fire-starting |

| 1st Century BCE | Ancient Rome | Glass Spheres | Glass | 2x to 3x | Reading aids |

| 1st Century CE | Alexandria, Egypt | Burning Glass | Glass | Varied (focused sunlight) | Fire ignition and experiments |

| 11th Century | Islamic World | Optical Lenses | Glass | Up to 5x | Scientific experiments and vision correction |

| 13th Century | Europe | Reading Stones | Quartz or glass | 2x to 3x | Magnification for reading |

The utilitarian nature of ancient lenses extended far beyond simply aiding weak eyesight or starting fires. Their magnifying capabilities found utility in various crafts and scientific observations.

Artisanal Craftsmanship

For artisans engaged in intricate work, such as gem cutting, jewelry making, coin engraving, or carving small seals, even rudimentary magnification would have been invaluable. A clearer view of fine details allowed for greater precision and artistry. Imagine a jeweler meticulously setting tiny stones into a ring; a simple lens, even if held by hand, would dramatically improve their ability to align and secure each precious gem. The pursuit of perfection in these crafts would have naturally driven the demand for tools that enhanced visual acuity.

Astronomical and Observational Tools

While robust telescopes as we understand them would not emerge until the 17th century, the seeds of astronomical observation were sown much earlier with the use of simple magnifying elements. The ability to observe celestial bodies with slightly enhanced detail, even if only through a hand-held lens, could have aided in star charting or understanding planetary movements. While direct evidence of ancient civilizations using lenses for advanced astronomical observation is limited, the theoretical understanding was gradually developing.

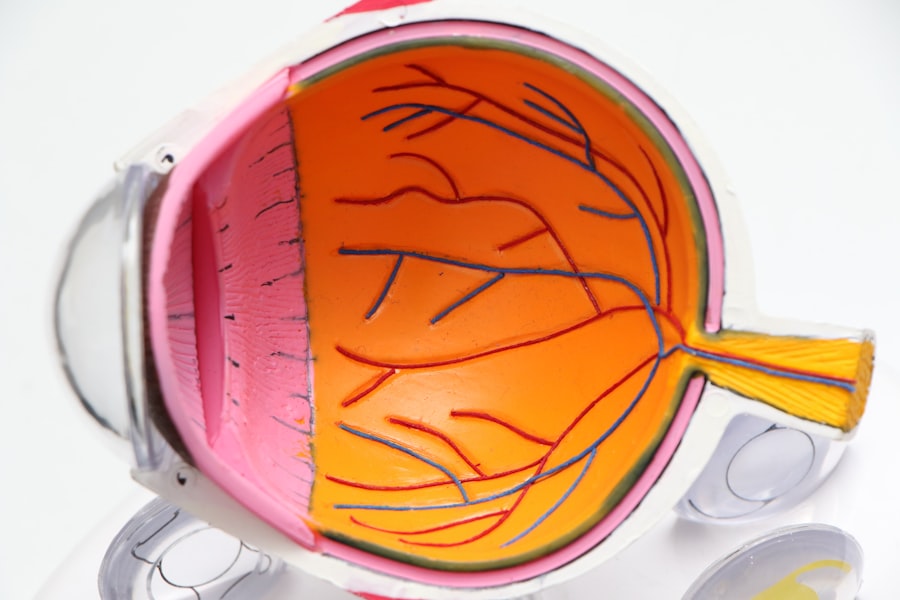

Medical and Surgical Applications

Beyond cauterization, early lenses may have played a role in rudimentary medical diagnostics or minor surgical procedures. A surgeon inspecting a wound for splinters or attempting to suture delicate tissues might have found a simple magnifier advantageous. Although microscopes were centuries away, the concept of visually enhancing small details for medical purposes would have been intuitively appealing to healers and practitioners.

The Legacy and Trajectory into Modernity

The journey of ancient magnification lenses culminates in the intricate optical instruments of today. These seemingly simple objects were not just curiosities; they were catalysts for intellectual and technological advancement.

From Speculums to Modern Microscopes

The progression from a simple “reading stone” to the powerful electron microscopes of today is a testament to cumulative knowledge and technological refinement. Each iteration, from the earliest plano-convex lenses to the compound microscopes of Hooke and van Leeuwenhoek, built upon the discoveries and techniques of its predecessors. The initial understanding of light refraction, even if empirical, paved the way for sophisticated lens design, chromatic aberration correction, and ultimately, the ability to peer into the cellular and even subatomic realms.

The Ever-Expanding World of Vision

The invention and refinement of magnification lenses fundamentally altered humanity’s relationship with the unseen. The macroscopic world, once a boundless frontier, became open to systematic exploration through telescopes, extending our dominion to the stars. Concurrently, the microscopic world, previously an unimaginable void, was gradually revealed through microscopes, opening up new fields of biology, medicine, and material science. These twin pillars of optical innovation, both stemming from the humble origins of ancient lenses, continue to reshape our understanding of existence, from the largest galaxies to the smallest viruses.

In conclusion, the story of ancient magnification lenses is not merely a historical footnote but a foundational chapter in the annals of human curiosity and ingenuity. From a chance observation of light-bending through water to the deliberate crafting of polished crystals, these early optical tools were far more than just aids for the visually impaired. They were windows into new realities, propelling civilizations forward and laying the essential groundwork for the scientific revolutions that would eventually transform our understanding of the universe, both vast and minute. Their legacy is etched into every pair of spectacles, every microscope, and every telescope, a silent testament to the enduring power of sight and the human drive to see beyond the immediate.

SHOCKING: 50 Artifacts That Prove History Was Erased

FAQs

What are ancient optics?

Ancient optics refers to the study and understanding of light, vision, and optical phenomena in ancient civilizations. It includes early theories about how light travels, how the eye perceives images, and the use of lenses and mirrors to manipulate light.

When were magnification lenses first used?

Magnification lenses were first used in ancient times, with evidence dating back to around 700 BCE in Assyria. The earliest known lenses, such as the Nimrud lens, were made from polished crystal and used to magnify objects or start fires.

Which ancient cultures contributed to the development of optics?

Several ancient cultures contributed to optics, including the Greeks, Romans, Egyptians, and Mesopotamians. Greek philosophers like Euclid and Ptolemy studied light and vision, while the Romans used glass lenses for magnification and reading aids.

How did ancient lenses work for magnification?

Ancient lenses worked by bending light rays to enlarge the appearance of objects. Convex lenses, made from glass or crystal, focused light to create a magnified image, helping with tasks like reading small text or examining details.

What is the significance of ancient optics in modern science?

Ancient optics laid the foundation for modern optical science and technology. Early discoveries about lenses and light behavior influenced the development of eyeglasses, microscopes, telescopes, and other optical instruments used today.